F-L-SCHMIED, Pathé ART DECO,

&

THE WORLD’S MOST BEAUTIFUL 78 LABELS

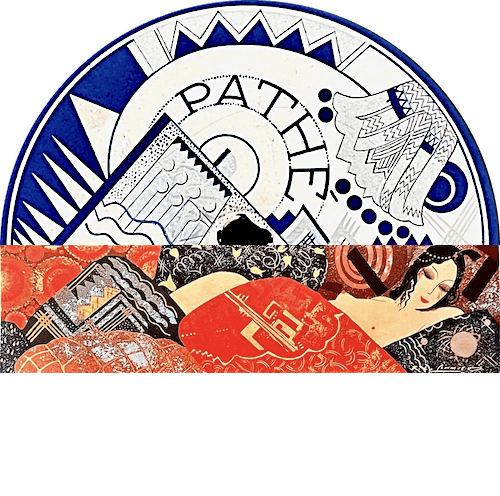

Pathé Records could have taken the cheap and easy way and used its in-house graphic artists to design a unique label for its new classical series inaugurated in the early 1930s. Instead, hoping for something special, colorful, and eye-catching, the company contracted with one of Paris’s most celebrated Art Deco artists and designers.

His name was François-Louis Schmied (1873-1941).

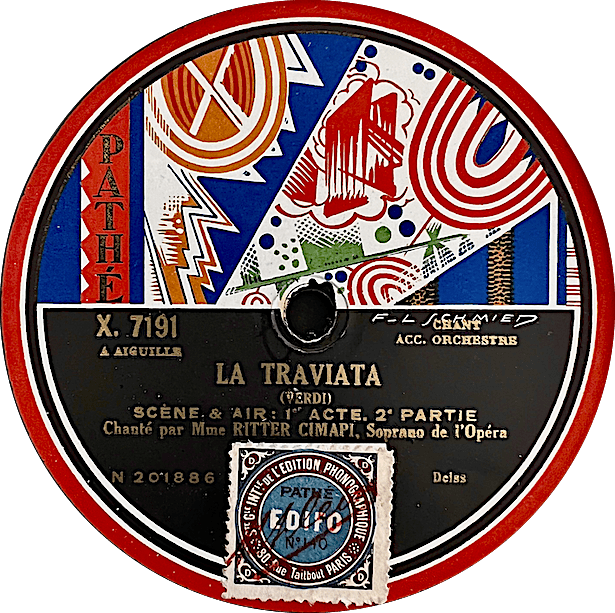

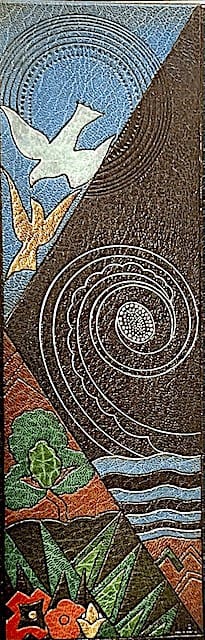

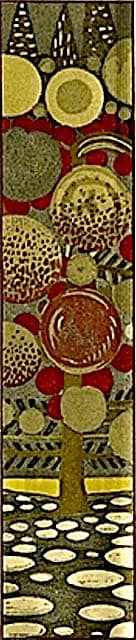

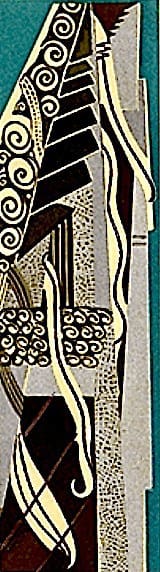

More than just a new label, Schmied presented Pathé with three beautiful mini-works of art.

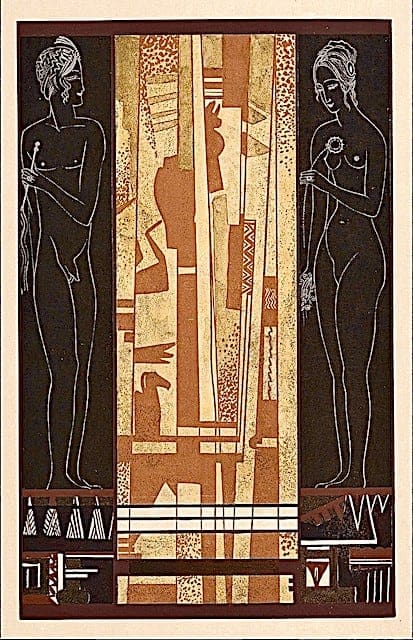

Schmied’s artistic talent was both unlimited and untamed. He was an illustrator, painter, engraver, bookbinder, printer, typographer, editor, publisher, and wood block artist. And a designer of 78 rpm labels for Pathé.

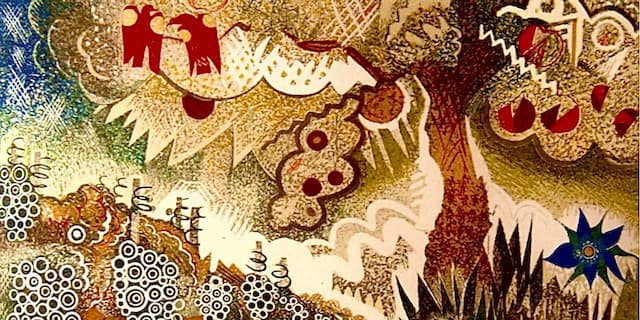

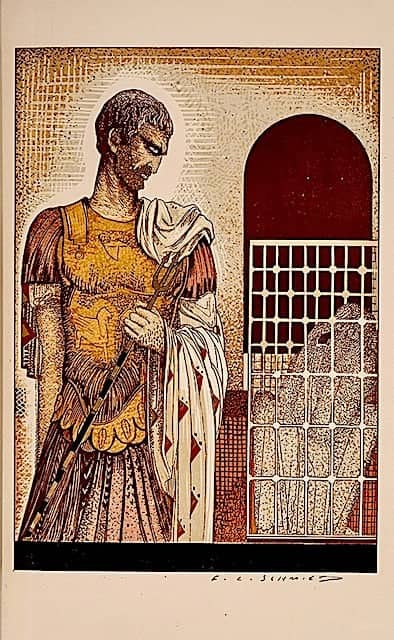

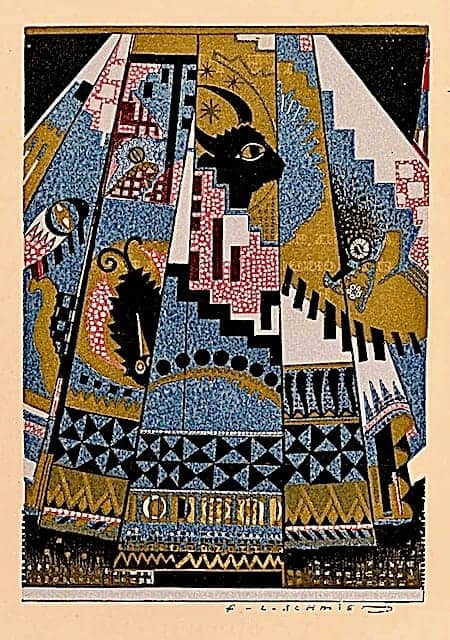

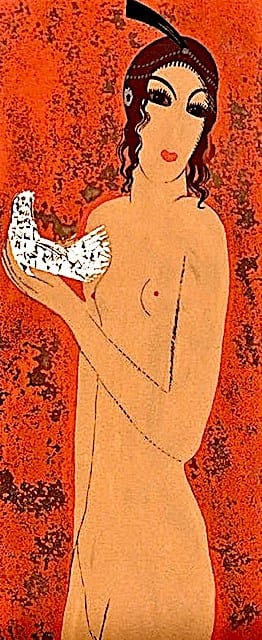

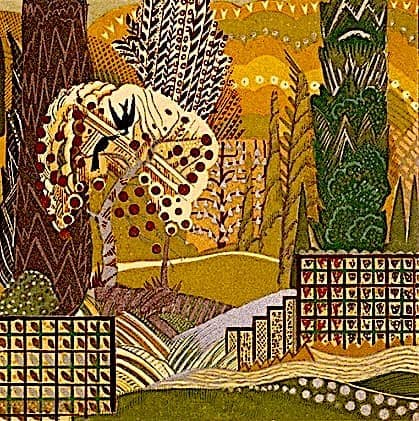

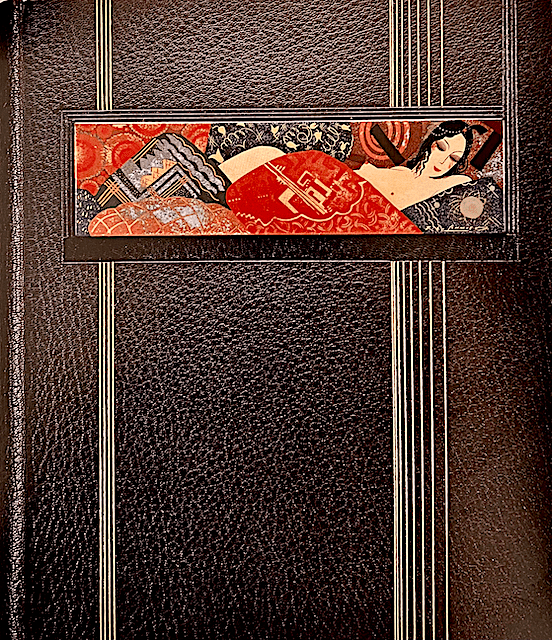

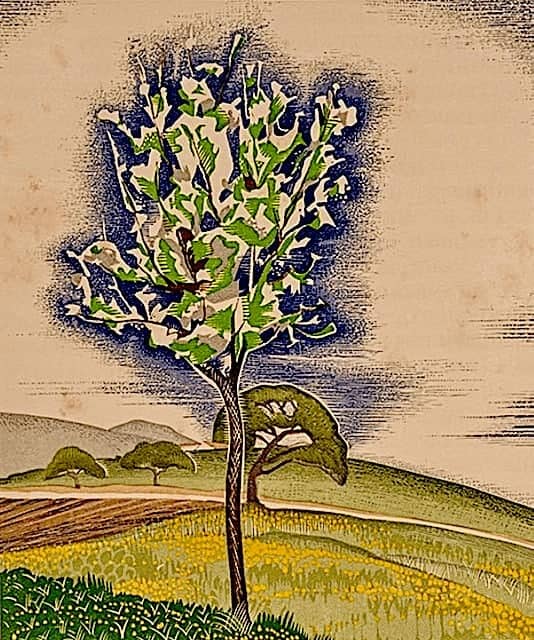

[Schmied’s] exquisite illustrations and page designs are pure Art Deco style. He was able to assimilate all of the tendencies and sources of the style—the elongation of figures, the geometricism, the eccentric arrangements, the transformation of reality—and evolve a personal style of virtually unmatched beauty.

Patricia Frantz Kery, 1986

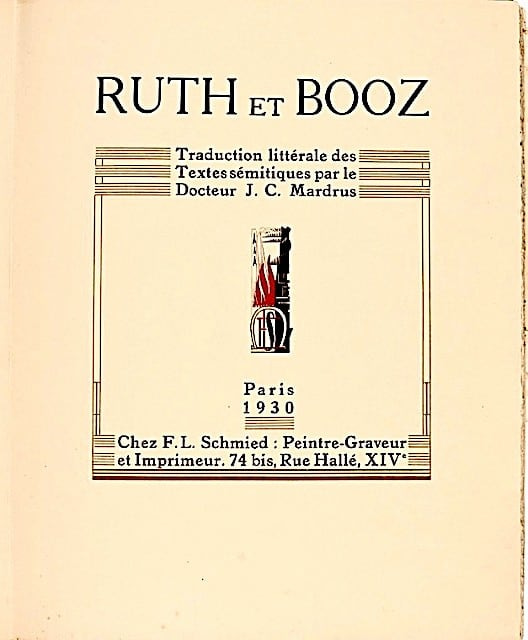

In all aspects of his art and craft Schmied was consistently committed to producing works of the highest esthetic quality. Obsessive and demanding, his true love was the creation of special edition books printed in limited quantities (one edition was limited to twenty copies), and filled with his wonderful art. Those editions commanded high prices at the time, and continue to do so today on the rare book market. Nice copies of some of his more popular books can sell for over $25,000.

The Great Depression that began ravaging the United States with The Stock Market Crash of 1929, had not yet jumped the ocean to Europe; consequently, Pathé had the money to pay for the best when it came to the label design for its new music series with an emphasis on Art Deco style. The series would be called “Pathé-Art”. It was logical, therefore, for the company to reach out to Schmied, one of the most renowned French artists in the Art Deco field.

Unfortunately, both the company and the artist were already standing on a crumbling economic cliff. The Great Depression was coming and soon engulfed France like it had much of the world. Pathé’s bottom line suffered as the company saw record sales dry up. In the future, Pathé artwork would revert to the less costly services of the low-paid graphic artist.

Ironically, with his design of the three Art Deco labels for Pathé, Schmied’s art career had reached its pinnacle. With a stagnant economy there was less and less money in the pockets of art buyers. Schmied’s art was exclusive, exquisite, and expensive. It became unaffordable.

Pathé would survive, but not the professional art career of François-Louis Schmied.

The Pathé-Art Record Labels

Below are the three beautiful 78 rpm record labels that François-Louis Schmied designed for Pathé in the early 1930s. The labels were used exclusively for classical and light classical music recordings. Many classical recordings of the period were pressed on the longer twelve inch discs, and Schmied’s labels seem to have been reserved for these special recordings, although there are reports that they were occasionally used for ten-inch classical records.

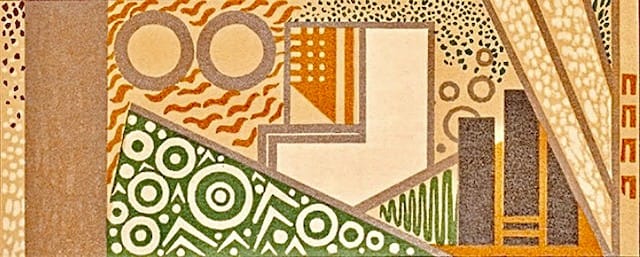

As can be seen below, many elements of Schmied’s art can be found in the Art Deco designs that the artist used for his three Pathé record labels. The designs he did for Pathé could have easily fit into his books of Art Deco creations.

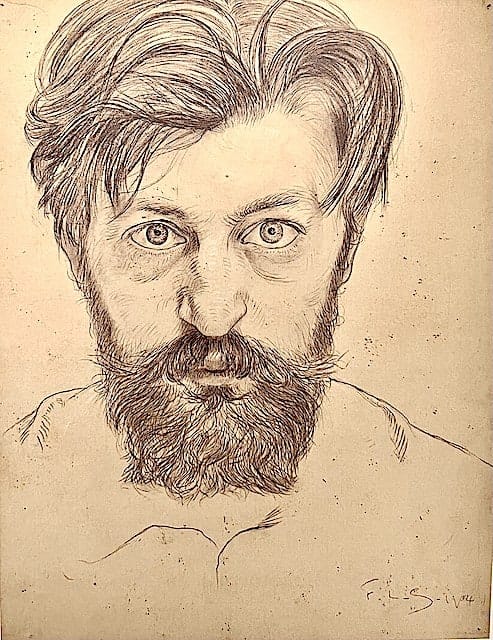

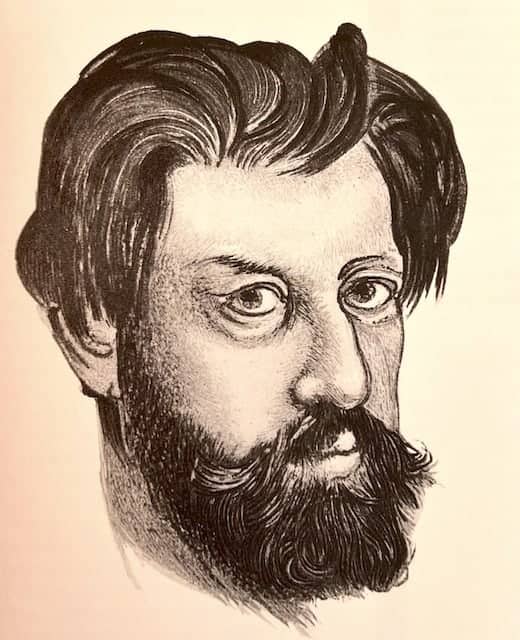

François-Louis Schmied

The artist was born in 1873 in Geneva, Switzerland, to a middle-class Swiss father and a French mother. As a young man he saw himself becoming an artist, while his father pushed him to pursue a business career. But as he later explained, it was his mother’s French blood that won the day, and he apprenticed himself to local artists. Finally, he traveled to Paris in 1895 where he re-invented himself as François-Louis Schmied, French artist. He married and had two children. His son Theo would also become a respected artist and would work with his father.

Prior to World War I, a struggling Schmied learned a number of art styles and techniques as he sought success in the art world. His work, while excellent, didn’t stand out in the highly competitive French art market.

Then war changed both Schmied and art in France.

Although over forty when the war began, Schmied enlisted in the French Foreign Legion. He came out of the service missing one eye. It might appear such loss would be a disability for any artist, but it seems that working with just the remaining eye helped Schmied refocus his world into distinct shapes, patterns, and colors. Rather than a liability, it helped him to reframe reality and work it into his own distinctive art style.

The other event that set Schmied on the road to artistic success after World War I was the advent of the Art Deco movement born in France. It was as if he had been waiting for this new style of art to blossom and inspire his career. Soon he was considered one of the founding fathers of Art Deco in France. And a very successful founder, both artistically and financially. His art sold well, and in turn he bought a yacht, gambled heavily, and enjoyed the good life in Paris, hobnobbing with politicians and fellow artists.

From 1919 to the advent of The Great Depression in France in the early 1930s, Schmied was at the top of the French art world

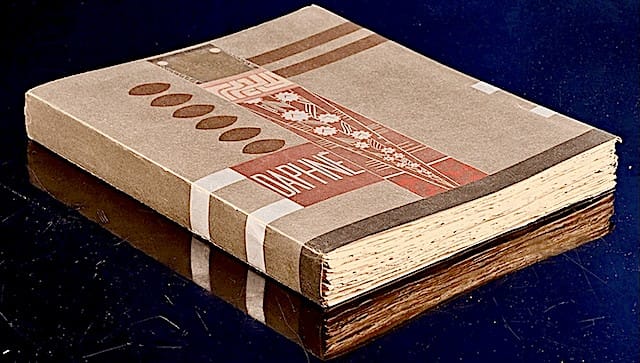

Schmied found his favorite artistic niche in the exclusive field of Art Deco-designed book making. Here he learned to control all aspects of designing, making, and printing books, from the tooling of the leather bindings to the styles of typography. Each book he produced provided a home for his illustrative art.

As Schmied became more successful in the book world, he opened his own studio in order to handle all aspects of making the intricately designed volumes for a speciality market. It was a market consisting of collectors and dealers. Not only was one of Schmied’s books a piece of art in itself, but the purchaser saw it as an investment that would appreciate in desirability and value over time.

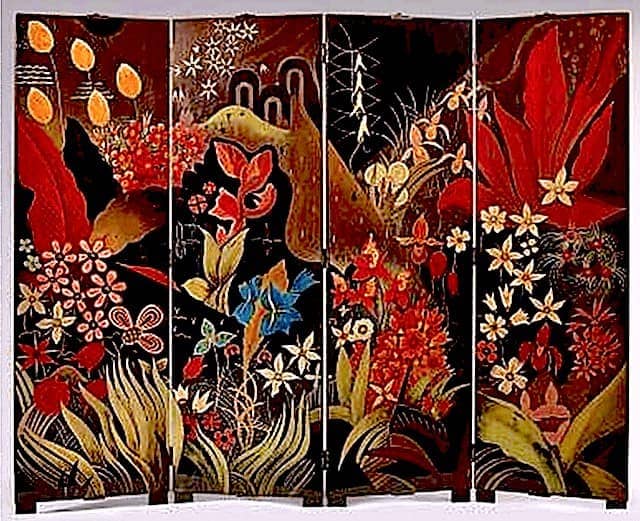

In his studio Schmied not only produced his own books, but he also opened its doors to provide specialized services for other bookmakers. The studio’s artistic work wasn’t limited to books, however. Schmied established a collective of artists and craftsmen who produced various types of artwork for themselves, as well as collaborated with Schmied on his projects. Schmied also produced tapestries and screens. A number of respected artists worked with Schmied over the years, including his son who in the 1920s would take charge in running many of the day-to-day studio operations.

Below is an art screen that was a Schmied collaboration . . .

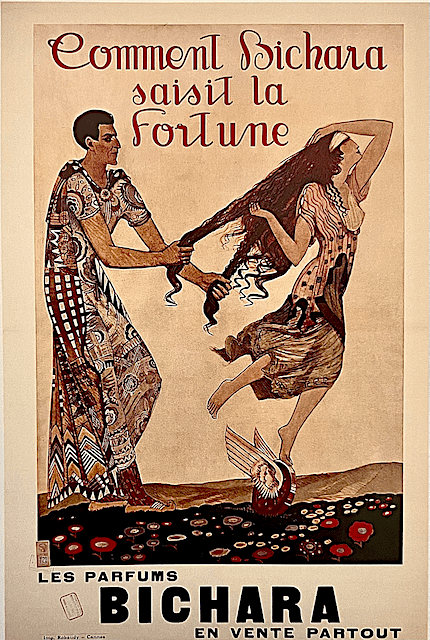

. . . and a perfume ad he created . . .

. . . plus, a menu for a fine restaurant.

Schmied was secretive about many of the techniques he used in his artwork and book making. Whereas one artist might take a dozen steps to create an art piece, Schmied would triple that. His eye was always on the detail. Hence, most of his books took two to four years to complete, never being printed in editions larger than two hundred. At art shows he would preview an upcoming book by exhibiting his completed illustrations, thus securing buyer subscriptions.

With the advent of the Great Depression in France, Schmied’s operations quickly fell victim to cash flow problems, resulting in his eventual liquidation of all his assets and the shut down of his studio by the mid-1930s.

He came to Paris as a poor artist and, as such he would leave it.

Pathé Records

The Pathé Record Company in Paris that hired François-Louis Schmied to design its Art Deco record labels in the early 1930s was, oddly enough, not French but British.

Pathé, founded in France in 1896 by four Pathé brothers, began life manufacturing phonographs and records. After the turn of the century it expanded into photography, film, and film production. In the first half of the twentieth century it became the largest film company in the world. For the rest of the century it would remain one of the world’s largest communication companies.

The advertisement below was published in 1899, soon after the company’s founding.

The company’s entry into the recording business saw Pathé first producing cylinder recordings, and in 1904 it began manufacturing disc records. Pathé’s recording subsidiaries were soon established throughout the world. As Pathé’s communication business continued to diversify and expand in different directions, parts of the operation began to be sold off. In 1928, Pathé divested itself of its French recording operation, selling those assets to the British Columbia Graphophone Company.

Beginning in the 1910s, Pathé made the silhouette design of le coq part of its record advertising and its 78 record labels—both foreign and domestic. Shortly after the rooster’s arrival as a logo, the font for the company name design would change to cursive. The rooster adorning “Pathé” written in cursive would be the logo gracing most of the company’s pre-World War II 78s, both 10-inch and 12-inch.

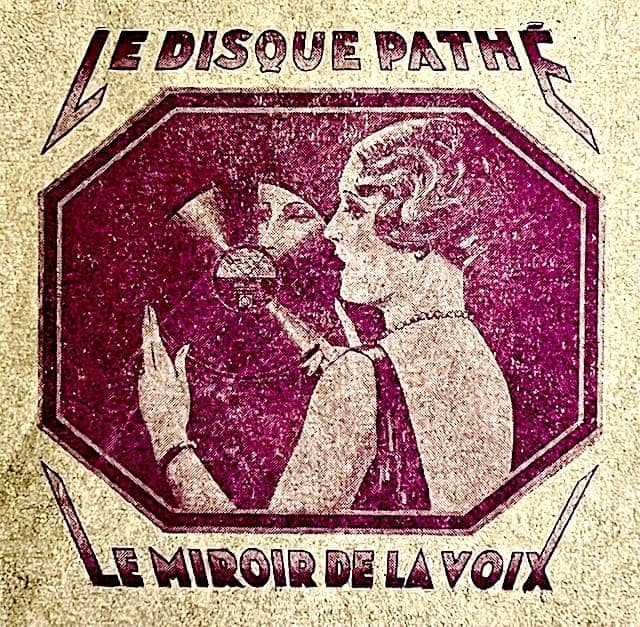

Schmied’s radical Art Deco label redesign for 1930-31, was not the first substantial deviation in the look of the standard record label for Pathé In the late 1920s Pathé had introduced its “mirror of the voice”—le miroir de la voix—label.

The colored illustration on the le miroir de la voix label of the stylish blonde woman with modern bobbed hair, wearing an evening gown exposing a wide swath of bare skin on her elegant back, suggested that this was a record for modern times. It certainly caught the eye. Both the cursive writing and the proud rooster were gone. The young woman appears to be staring into a hand mirror. But, look again. She is really seeing her reflection in the shining surface of a Pathé record.

The name “Pathé” is no longer bold, but rather resides sedately above the woman’s picture. Pathé used this label for select classical recordings, as well as a handful of jazz records.

The le miroir de la voix label was Pathé’s first effort to move its records past the staid designs of the past to market something more exciting and eye-catching.

The next wave in giving Pathé a truly modern label design was left to François-Louis Schmied. The le miroir de la voix label had opened the door that Schmied strode through with his skill in Art Deco design.

Schmied kept the le miroir de la voix label’s use of bold primary colors and its greater emphasis of the label’s artwork, along with less of a spotlight on the Pathé name itself. Now, one simply recognized it as being Pathé by the stylishness of the artwork.

For the three Art Deco labels, in fact, the Pathé name would take on three different styles and shapes, and would be buried within the abstract designs. Of the three, one Schmied label would be a rich blue, another a bold orange, and the last a multi-color label of primary colors: blue, green, red, and orange. Three different abstract Art Deco designs would make these record labels truly something different, perhaps even startling to much of the French record buying public.

One might ask, rightfully so, how can we be sure today that Schmied himself designed these Pathé labels, rather than the designer being some other artist who simply “borrowed” from Schmied? The answer is simple: Schmied’s regular art signature is found under each design.

Not only are the Pathé-Art Deco labels the only 78 labels to be designed by a renowned artist, but also they are the only ones graced by an artist’s signature.

Below is a photograph of a dapperly dressed François-Louis Schmied at the time he worked on the Pathé labels. The sunglasses were worn by him constantly after the loss of his eye during the war.

Perhaps Schmied would have done more Art Deco labels or maybe Pathé would have hired other famous French artists to design its labels, but for the fact that hard times had arrived.

Epilogue

François-Louis Schmied was never an artist for the masses.

Schmied was respected and feted by fellow artists and those in the French art scene, but most of his wonderful art was hidden on the pages of limited-edition books, which, in turn, were hidden in the libraries of rich book collectors. Therefore, his art was rarely seen by the French public. Consequently, when he vanished from his beloved Paris he quickly vanished from popular French culture.

Ironically, it was probably Schmied’s great success in [his] lifetime that caused [today’s] relative obscurity. The very high cost of his books so limited their distribution that they were seen by too few to establish a wide reputation, particularly as they were printed in very small editions.

Patricia Frantz Kery, 1986

Ironically, the closest Schmied ever came to introducing his art into popular culture was with the three Art Deco record labels he produced for Pathé.

A middle-class Frenchman might not have been able to afford an original edition of one of Schmied’s rare books, but he could nevertheless buy a twelve-inch Pathé 78 rpm with the brightly colored Art Deco label. And what if the buyer did not like classical music? He or she would still have seen the label being displayed, what with Pathé records being ubiquitous in French record shops in the 1930s. Even if that Frenchman didn’t know Schmied’s name. at least he was now familiar with the artist’s work.

And so it was that three of the great Art Deco creations of François-Louis Schmied—Art Deco 78 record labels—could be viewed by the public for free in the 1930s, inside a French record shop!

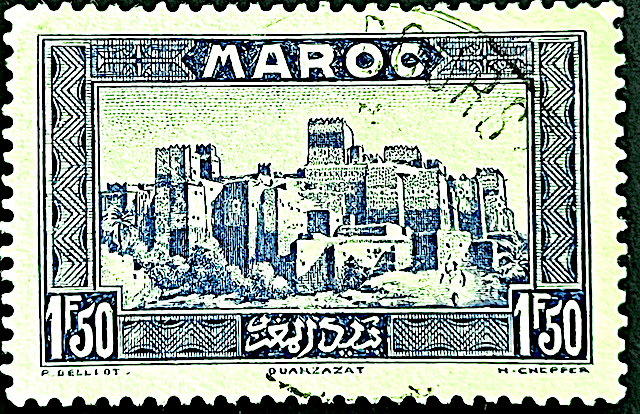

Schmied was always drawn to the exotic with much of his artwork depicting scenes and historical themes from North Africa and the Near East. Therefore it was fitting that, having to leave his home in Paris due to his financial straits, friends would find him a French colonial job 1500 miles away in Morocco, where he would spend the last years of his life.

Schmied was now in his sixties and the government post would provide him a modest income. He continued to pursue his artistic visions in his new home, although on a much smaller scale. Schmied seemed to find a new quietness and peace in his life in Tahanaout, Morocco. He died there of the plague in 1941, while ministering to sick and dying locals.

The images for the 78 labels, record sleeves, and other ephemera come from the Bowman collection. Excepting Schmied’s 78 labels, the images of Schmied’s artwork and photographs came from the books and websites listed in the bibliography.