Paramount

78 rpm

Record Sleeves

INTRODUCTION

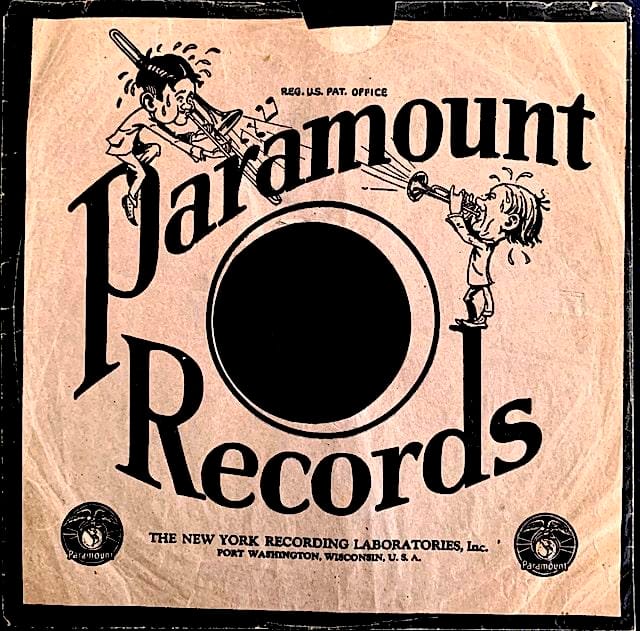

Paramount Records began life in 1917 as a subsidiary of the Wisconsin Chair Company of Port Washington, Wisconsin, and started producing 78 rpm records the following year.

The evolution from a chair maker to a record maker—from wood to shellac—was not so strange as it now seems. Being a furniture manufacturer, Wisconsin Chair Company had obtained a contract to build phonograph cabinets for Edison Records. Upon becoming proficient in the job the company decided to start building its own line of phonographs. From there it was only a short step to starting its subsidiary New York Recording Laboratories, Inc. (based in Port Washington); it would be the parent company of Paramount Records, that in turn would produce records that would go with the record players.

Decal for Paramount Phonograph

Ultimately the phonograph venture would fail after a few years, but Paramount 78s would continue to be pressed until the company went bankrupt in the Great Depression.

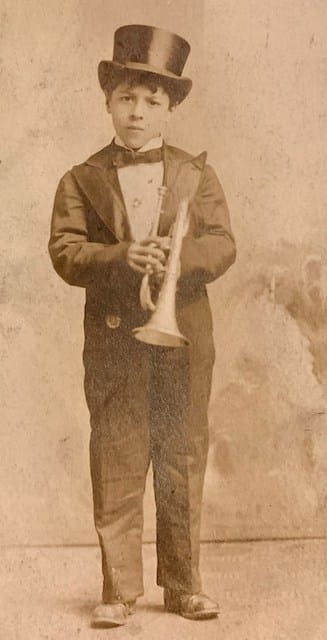

Initially, Paramount 78s sold poorly. Their recording and pressing quality left much to be desired. Plus, the company could only boast of a limp roster of second-line White recording artists. It was not until the early 1920s with its recording of Black jazz and Blues—including artists such as Jelly Roll Morton, Ma Rainey, and King Oliver—that Paramount came into its own.

Suddenly, Paramount had found its niche.

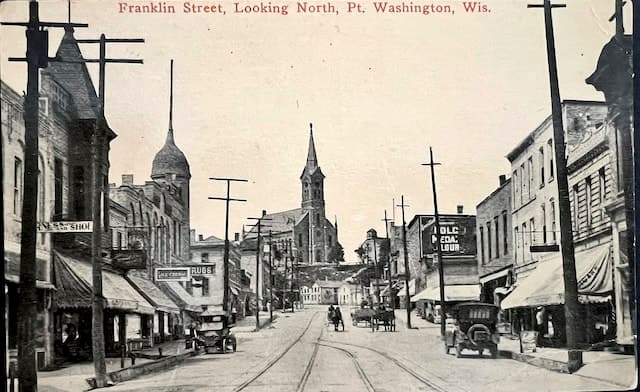

Port Washington in the mid 1910s, about the time Paramount Records started business.

Port Washington, shown above, would be the corporate center for both the Wisconsin Chair Company and Paramount Records, but the actual furniture making and record pressing would take place in the nearby village of Grafton, Wisconsin, shown below. Initially, Paramount recorded most of its 78s in rented studios in the Chicago area. In 1929, Paramount built its own recording studio in Grafton, and its recording facilities remained there until the company’s demise in 1932.

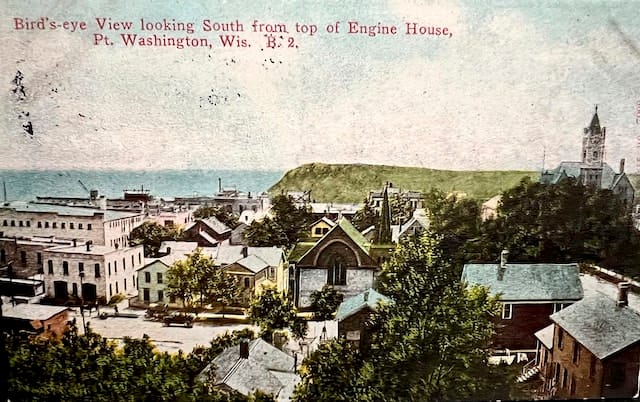

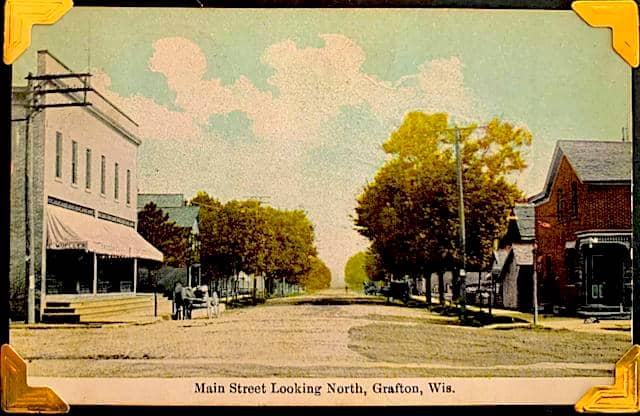

From 1918 until 1932, Paramount Records pressed 78s at its plant in Grafton, and it opened its recording studio there in 1929. This is a view of Grafton in the mid-1910s.

Below are the half dozen 78 record sleeve styles used by Paramount Records from about 1918 until its last shipment of records.

PARAMOUNT SLEEVES

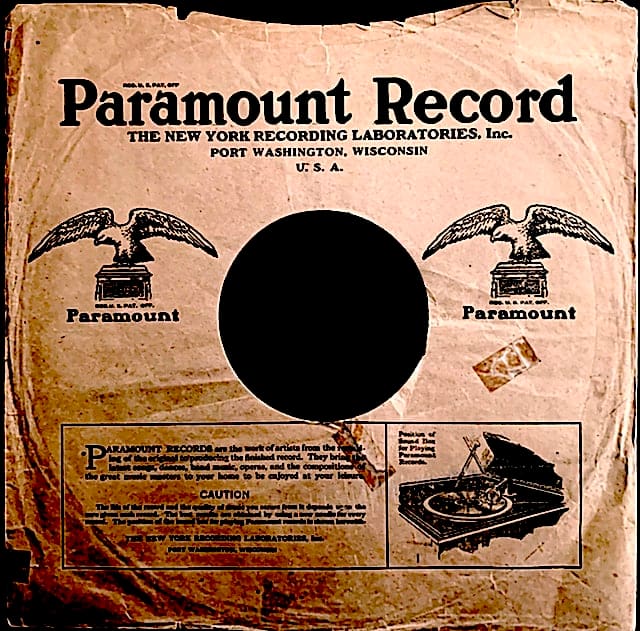

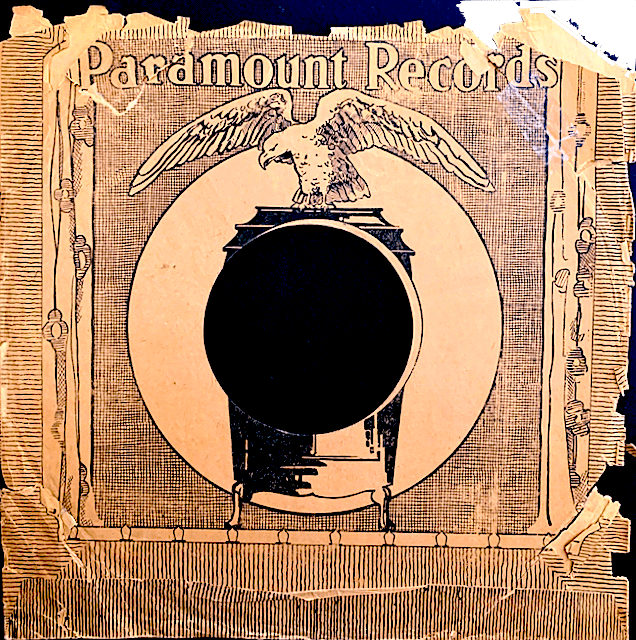

Front

Back

The above sleeve may be one of the earliest ones made to protect new Paramount 78s coming off the presses. This one can be dated about 1918, given its emphasizing of “Popular and War Songs”—a clear reference to World War I. The “Paramount eagle” surfaced on this early sleeve and would reappear on all subsequent ones.

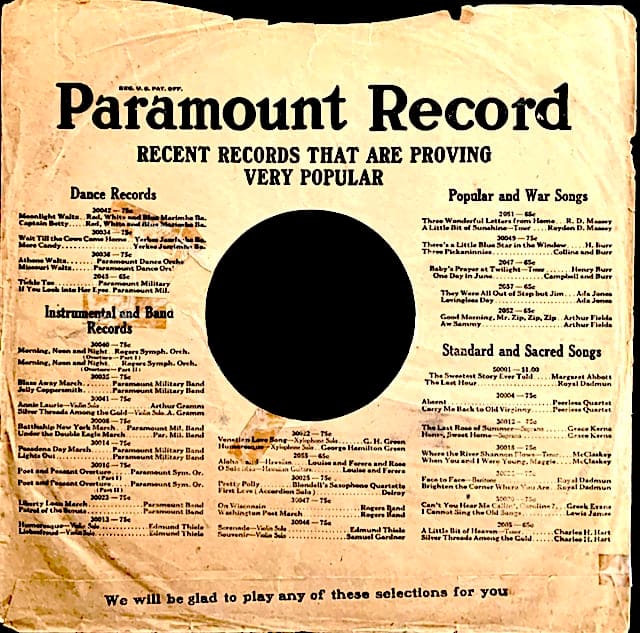

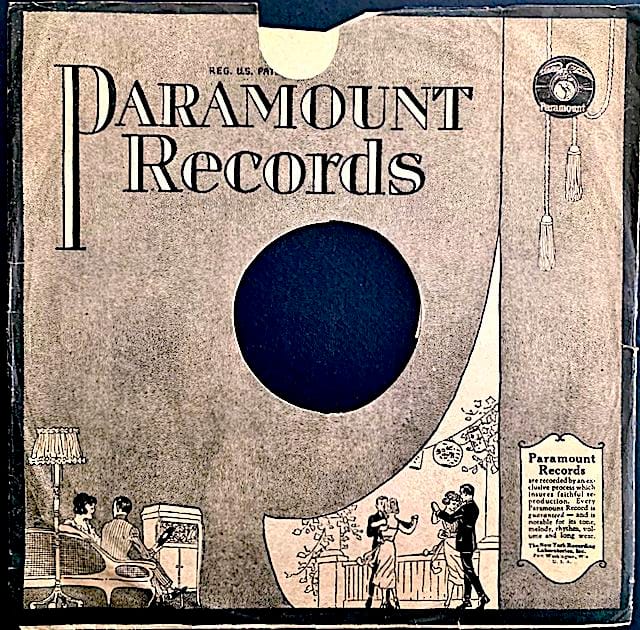

Front

Back

To survive as a middle-weight contender in the heavy-weight world of the recording industry, Paramount had to be creative, both in it marketing, as well as in its advertising style. That included record sleeves. This circa 1920 sleeve design of silhouetted dancers on a banded background and a Paramount record player on a bed of intricate cross-hatching is eye-catching. It turns the cheap pulp paper the sleeve is printed on into an artistic asset.

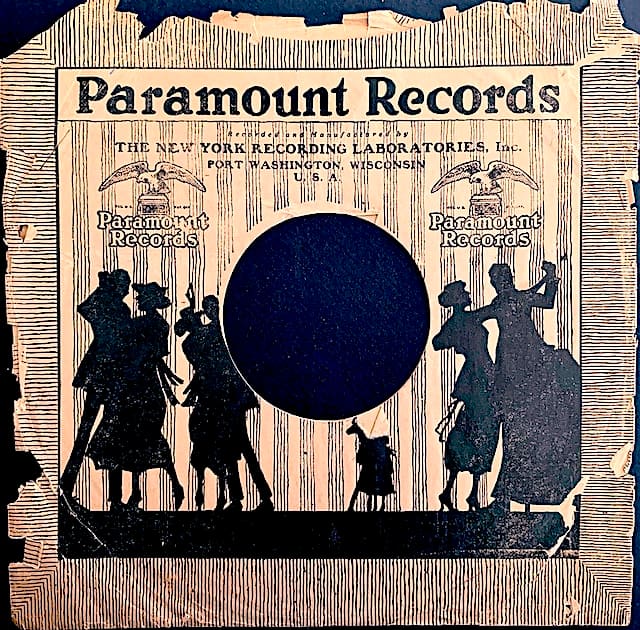

Front

Back

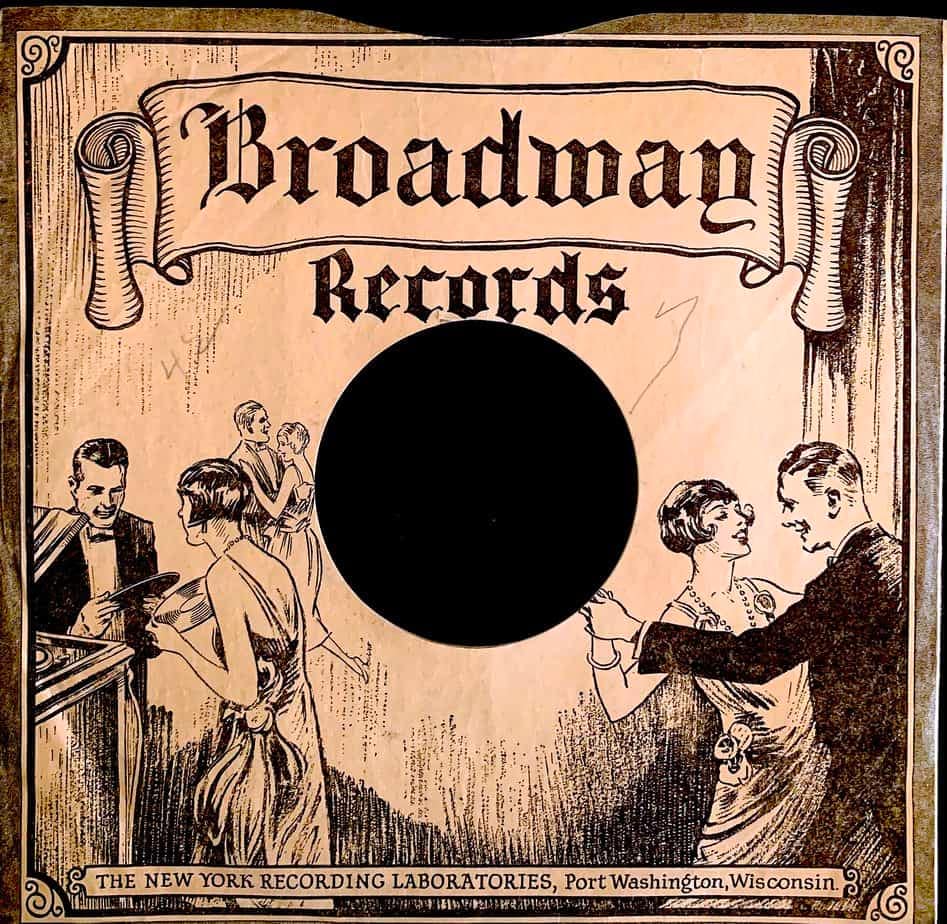

The first two 78 sleeves shown above are rare. This third one directly above, however, is relatively common today. There are two styles. They are both the same on the front, but the earlier of the two is blank on the back—something surprising for Paramount considering how much advertising could always be crammed on the back of a sleeve. The White dancers and listeners portrayed on this sleeve probably date its creation to about 1923 or 1924, just before Paramount made a shift to emphasizing Blues and Black jazz. This style sleeve was used further into the 1920s exclusively for the company’s roster of White artists, including its hillbilly ones

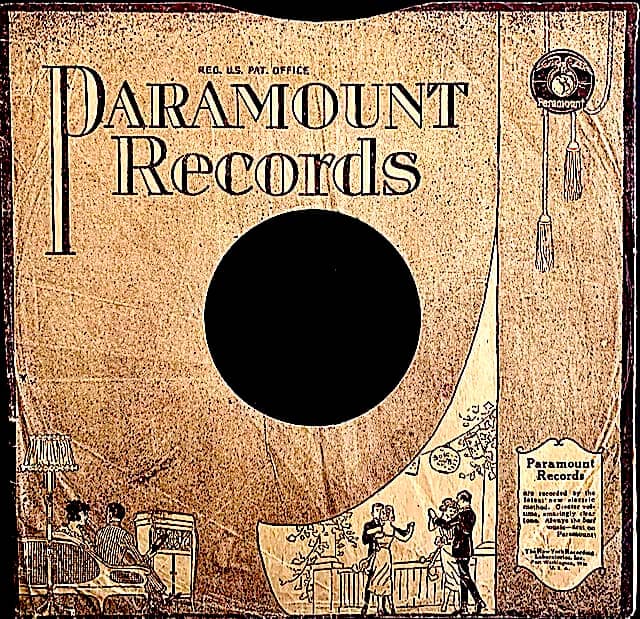

Front

Back

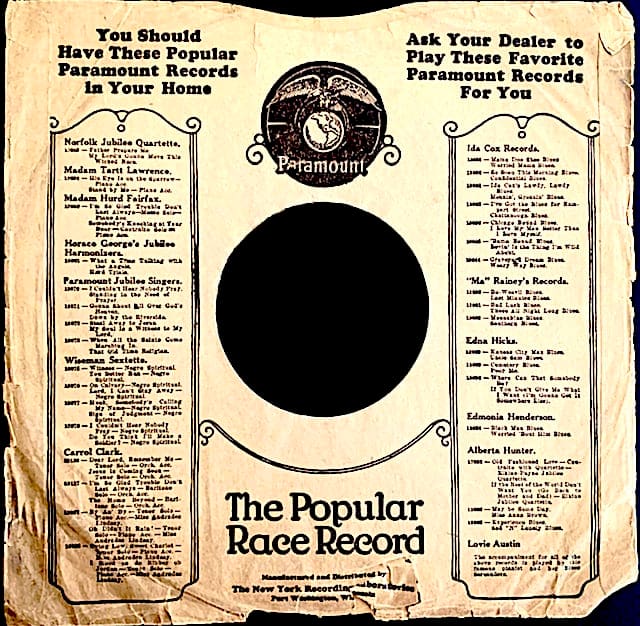

The sleeve shown above for a 1929 Paramount record is obviously repurposing its cover artwork from the earlier preceding sleeve, combining it with the advertising side of a Blues sleeve. We know the approximate date of this sleeve because some of the songs by Blues artists listed on the back were recorded in late 1928 and not released until the following year. In addition, the graphic layout style on the back of the sleeve is also reusing another earlier sleeve design, as will be seen below. This “composite” sleeve is an interesting juxtaposition of social groups: White society figures on the front, with Blues artists and songs on the back. Operating on a shoestring budget, Paramount usually let no supplies go to waste. How this sleeve came to be may simply be because new 78s needed new sleeves, and the Paramount crew put these sleeves together in a pinch from the materials available.

Front

Back

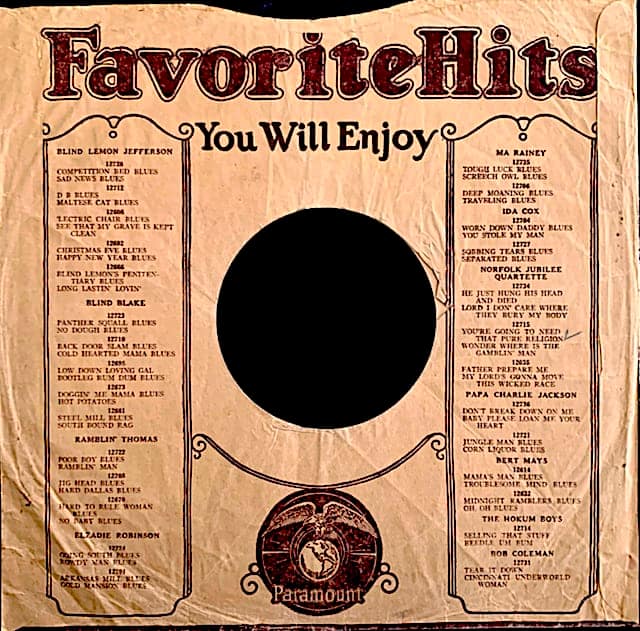

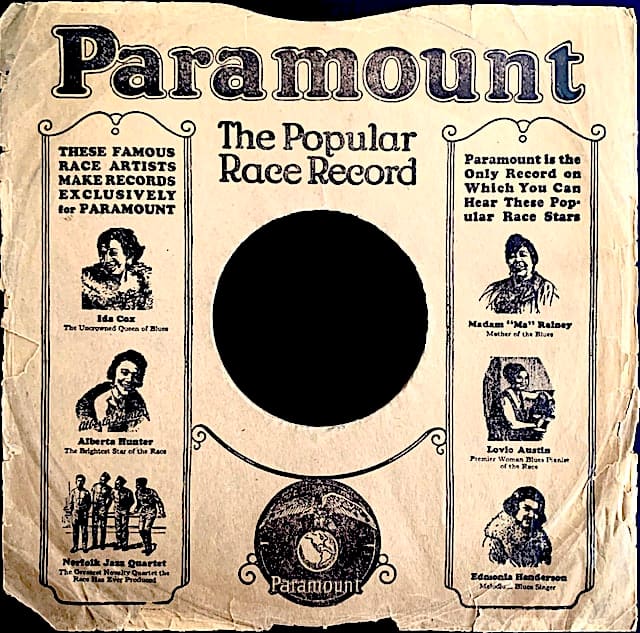

Some of the songs listed on the back of this sleeve would not be released until early 1924, which gives us an approximate time period as to when this sleeve, one designed especially for Black music, came into usage. This sleeve is easily found today. Until the end of Paramount, this would be the sleeve that accompanied most of its Blues records, with the back used as an update for the company’s newest releases. It is the sleeve design that is today most associated with Paramount records.

Front

Back

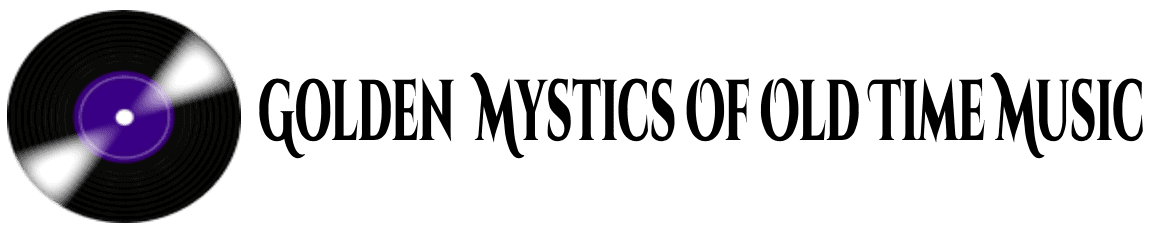

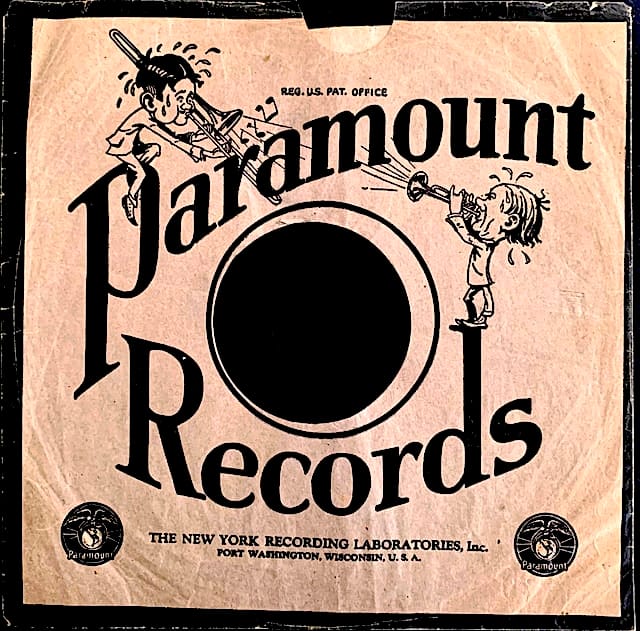

The artwork on the above sleeve is—stylewise—unlike what was traditionally used by Paramount for its advertising.

Further, it is today so rare that it could be considered the Holy Grail of Paramount record sleeves. The mere fact of its scarcity suggests that it either wasn’t on the market for long or wasn’t used often. But why? After all, its humorous cartoon musicians make for a truly unique sleeve, one more creative than most. Its lightheartedness certainly caught the buyer’s attention.

Even trying to date this sleeve is difficult.

The eBay seller of the sleeve thought perhaps that it dated to the early 1920s because it was found in a dusty Victrola with an early Blues record.

According to the seller, he found a small stack of blue-label Paramounts 78s from the early 1920s inside a Victrola in the Birmingham, Alabama area. Some time later he bought the Victrola primarily to obtain the records. One side of Paramount Number 12022 by Ida Cox and Lovie Austin was “Graveyard Dream Blues”. That particular song wasn’t recorded until October, 1923, which means that the record wasn’t released until late 1923 or early 1924.

The copy of“Graveyard Dream Blues” found by the seller was in this particular sleeve. On the back of the sleeve a previous owner had written the song’s record number, 12022. So apparently the record and sleeve belonged together.

Does this mean that this sleeve was from the first half of the 1920s? Maybe not.

Alex van der Tuuk has a different theory.

Over the past couple of decades van der Tuuk has become the pre-eminent authority on the history of the Paramount company and its output of 78 records; he has written and co-written a number of related books.

One book he helped put together was Paramount: The Rise and Fall (1917-1927), that accompanied “Third Man Records” two-part book-record-compact disc sets documenting Paramount Records. In this book Paramount 78 sleeves are illustrated, including the “Holy Grail” sleeve. Van der Tuuk stated in the book that he believed the sleeve may have come out about 1927.

Van der Tuuk said he settled on this particular year because the style of the artwork better reflected the second half of the 1920s more so than the first half; also, he suggested, in 1927 Paramount needed a special sleeve design to help inaugurate its new series of recordings by White jazz and dance bands.

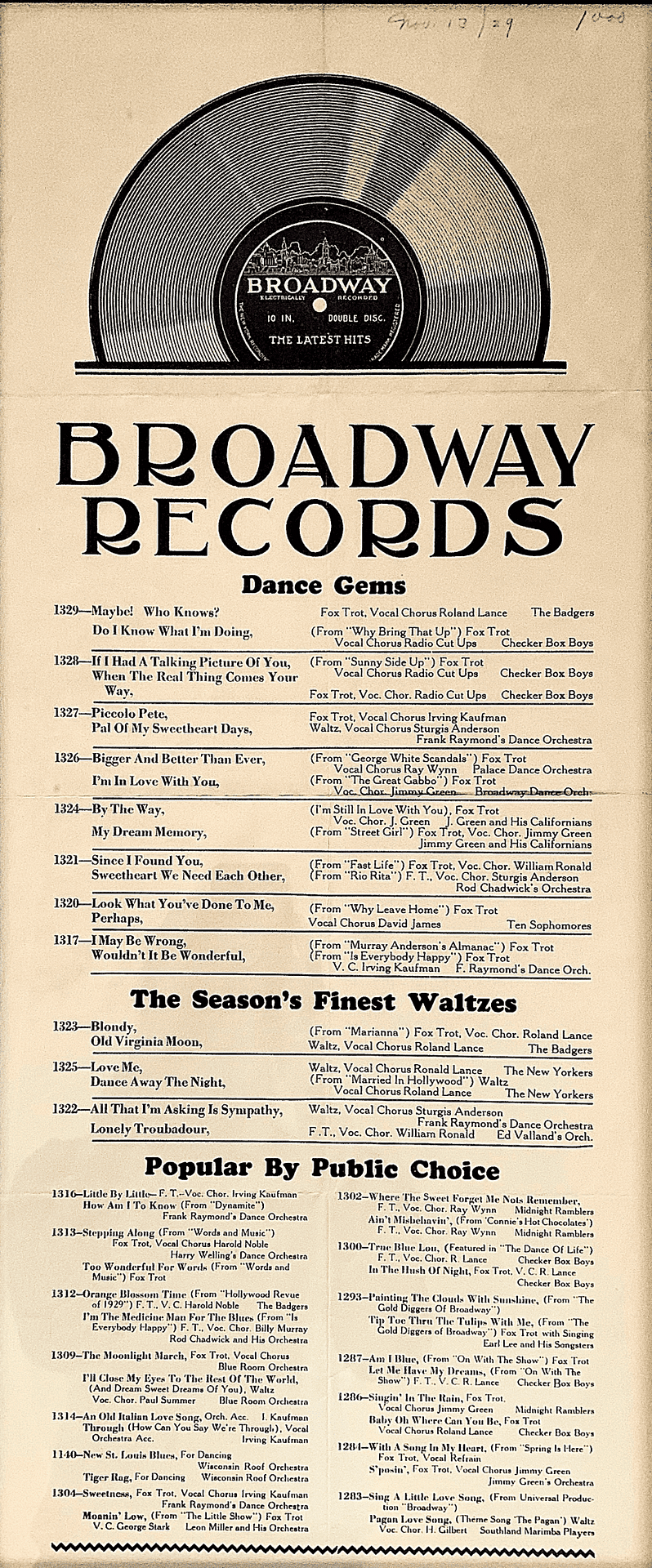

In the early 1920s most Paramount band recordings were by Black groups. This shift in 1927 to White bands brought into the studio many Midwest musicians from local bands such as Bill Carlsen and His Orchestra, Sig Heller and the Carolina Cardinals, and Wing Toy and His Orientals. In addition, Paramount would record nationally-known White artists using pseudonyms: Lou Gold and His Orchestra became the “Checker Box Boys”, while Harry Reser and his band emerged as the “Midnight Ramblers”. “The Badgers”, on the other hand, was simply a catch-all name used for at least a dozen different prominent White bands—as well as one Black band, Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra.

Paramount issued some of these 78s under its own label, but the majority were pressed for “Broadway”, its “dime store” subsidiary. Broadway releases did not literally sell for a dime, but at “three for a dollar” they were a deal, provided you didn’t mind the substandard recording quality and the poor quality shellac for which Paramount was notorious.

Paramount would continue to record White bands from 1927 until its demise in 1932, generally releasing them on both its flagship label, as well as its dime store label. For those recordings actually released using the Paramount label it makes sense that Paramount would design a new record sleeve. But because most of these recordings were sold under the cheaper Broadway label, it seems that the “Holy Grail” Paramount sleeve never got into wide circulation, hence its scarcity among collectors today.

Special thanks to Alex van der Tuuk for his assistance.

All ephemera shown here are from the Bowman collection.