Louis, Fletcher, & Buster

New York City, 1924

When Louis Armstrong left Chicago in the summer of 1924, traveling east to New York City to join the Fletcher Henderson band—the preeminent Black band in the nation—he seemed much like a small town boy with a scholarship attending a prestigious East Coast university. He would never feel at home or completely accepted in his new environment—and he missed the home cooking.

Armstrong thought he was looked down on by his new bandmates in New York, which was true, at least up until his lips touched the mouthpiece of his trumpet.

Fletcher Henderson and Louis Armstrong were Black men born in the South, and both were blessed with tremendous musical talents. But there, the similarities ended.

Henderson was a light-skinned Black man who grew up in one of Atlanta’s middle-class neighborhoods; Armstrong was a dark-skinned Black man who grew up on the other side of the tracks, in New Orleans’ “Battlefield” district. Henderson’s father was a school principal and his mother was a teacher; Armstrong’s father abandoned the family and his mother at times turned to prostitution to support Louis and his sister. Henderson graduated from college; Armstrong graduated from reform school. Henderson learned music from his family; Armstrong learned music on the streets. Henderson thrived in high society; Armstrong scorned fellow Blacks who put on high society airs.

Henderson and Armstrong made for an unlikely musical couple, but they came together in 1924 simply because each needed the other.

Fletcher Henderson late 1920’s

Today, we think of Fletcher Henderson as leading one of the great jazz bands of the 1920s and 1930s. He did. But in 1924, what Henderson led was still a Black dance band playing popular music for White audiences. It had a stolid, ragtime feel.

Even White dance bands of the day were starting to “jazz” up their music, particularly by inserting a hot or jazzy solo or musical break into each number. However, musicians in such bands were still wedded to following printed music. So even the jazzy extras were usually scripted. What Henderson was looking for was an experienced jazz trumpet player who could improvise a hot solo. He had heard about Louis Armstrong, Chicago’s hottest horn player.

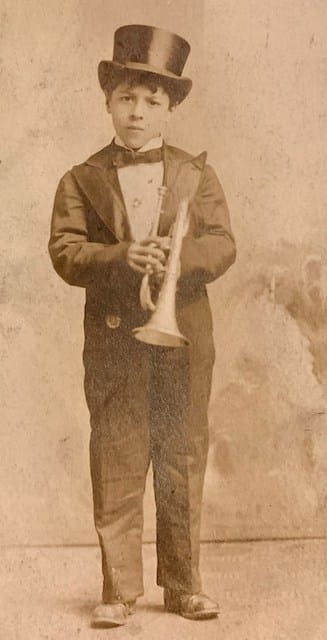

Armstrong’s initial musical training as a boy was at a New Orleans reform school. From there he developed his cornet skills playing on the streets. Next, he apprenticed himself to King Oliver, New Orleans’ best cornet player. When Oliver went north to Chicago, Armstrong was promoted to Oliver’s seat in the New Orleans band. Once comfortable there, Armstrong moved on, secured a job on the Mississippi riverboats, playing with professional musicians, learning to read music, and for the first time playing for White audiences. Finally, he answered the call to go to Chicago to play with—and in 1923, record with—King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, the best jazz band of the day.

It seemed that at each stage of his career Armstrong had always taken the logical next step in moving up the ladder. But when he left King Oliver in 1924 he found that he was only treading musical waters in Chicago. That’s when the call came from New York. Henderson needed him, but also Armstrong needed Henderson. Up until now, Armstrong had always played with fellow musicians from New Orleans. It was time for him to break out of his comfort zone.

Louis Armstrong’s year with the Henderson band would not be a particularly happy time for the trumpet player, and in later years he would grouse about the snooty ways of his boss and some of his fellow band members. He also complained about being restricted to his short jazz solos and rarely being allowed to sing. Yet, despite Armstrong being unhappy with his year at Henderson’s musical “university”, he nevertheless realized that he came out of it a better musician for the experience.

As for Henderson and his band, over that year they gradually absorbed much of Armstrong’s technique and style, such that by the time Louis left they were evolving into a truly great jazz band.

When Armstrong quit Fletcher Henderson’s band in 1925 he bolted straight back to Chicago— to his wife Lil and the friends and fellow musicians he had left behind. And to the home cooking he missed. Back in Chicago he would now be billed as “The World’s Greatest Trumpet Player”—advertising hyperbole certainly, yet the literal truth. Before the year was over he would be signed by Okeh to record with his own band. Never again, would he only be a sideman.

Okeh advertisement from 1930 for Louis Armstrong’s visit to Los Angeles.

On a personal level there was one thing that made playing in the Henderson band palatable for Armstrong. Early on, Henderson asked Armstrong if he could recommend a hot clarinetist for the band.

Armstrong suggested one that he had played with in the King Oliver band: Buster Bailey. Bailey was born in Memphis, but he had easily fit in with the New Orleans jazz crowd in Chicago. Henderson hired Bailey. Armstrong would now have a buddy in the band. And Bailey would also help to subtly transform the Henderson band.

Bailey would stay with Fletcher Henderson until 1927. He would then have a steady career in music, playing both in America and Europe with a number of prominent jazz bands. In 1965 he would re-team with his old New Orleans bandmate in “Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars Band”.

The above autographed 78 record (back and front) was won at auction about twenty years ago from Jim Prohaska, a record collector and dealer out of Cleveland. One side is signed by Louis Armstrong and the other by Buster Bailey. This was what Jim knew about the history of the record at the time:

The Henderson [78] came from the collection of a friend, Dave Ski. Many of the jazz greats visited Cleveland in the late 40’s and early ‘50s. Louis had many friends here in Cleveland (I have some excellent candid color photos of him visiting here during that time) and came to town quite often. Dave was a young collector at the time. I believe Louis was at the Cleveland Boat Show (c. 1950) at the time. Dave approached Louis with the Henderson. Louis got a laugh out of it, and gladly signed the record for him. Dave thought it would be fun to have Bailey’s autograph on the reverse. Dave doesn’t remember what, if anything, Bailey had to say. Enjoy!

If Bailey also signed the 78 label sometime around 1950, he was probably playing in the band of Henry “Red” Allen, another New Orleans trumpeter of renown.

Jim Prohaska is still in the 78 auction business, and his listings today are found in VJM.

All 78s and ephemera in this article come from the Bowman collection.