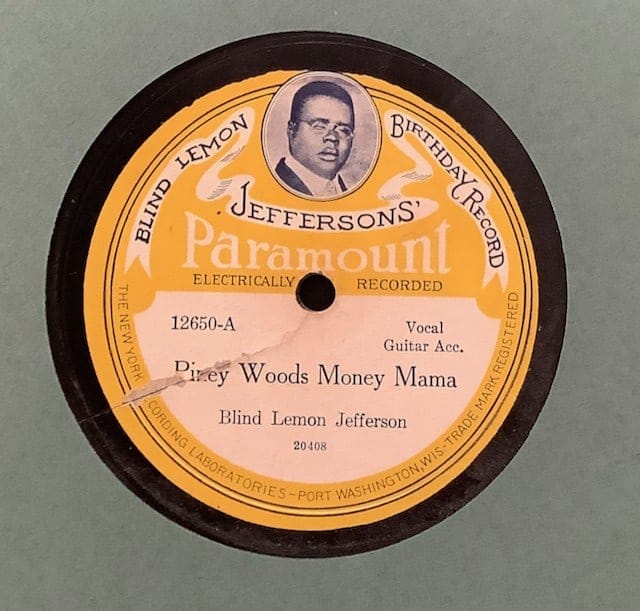

Paramount Portrait Record Labels

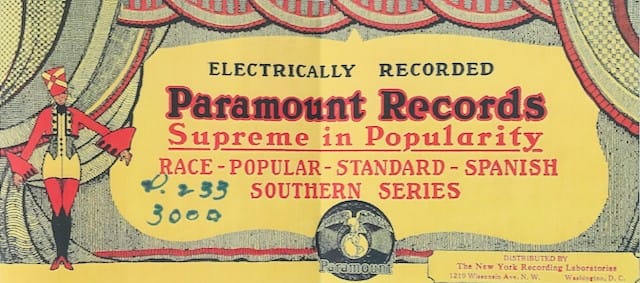

Paramount Records, located in Port Washington, Wisconsin, issued in the 1920s three 78 records with attractive portrait labels designed to promote its recording artists. Two of the records were by popular Black blues artists. The third was a sermon record by a regionally prominent White preacher out of Birmingham, Alabama.

As an enterprise, Paramount would always be a second-tier record company (compared to Victor or Columbia) that perpetually faced budget crunches. While issuing some of the greatest blues and jazz music of all time, Paramount ran its operation on a shoestring, putting out poorly recorded discs with inferior shellac pressings.

Paramount also short-changed its recording artists.

The company only had distributors in certain parts of the country, and consequently relied on mail orders, as well as Pullman Porters on trains traveling south, to put its 78s into the hands of Black buyers.

In search of success, Paramount was willing to try anything. It was founded as a subsidiary of a chair-manufacturing company, and in the 1910s it began to manufacture phonograph players and 78 rpm records. Its first issues of White artists were nothing to brag about, and Paramount might have faltered after a few years, but for the advent of the blues craze in the early 1920s. The company had some middling improvement in sales with female Black blues singers prior to signing up “Ma” Rainey in 1923. With Rainey the company began to experienced its first taste of success.

In 1924, Paramount issued its first portrait label, one featuring “Ma” Rainey. It waited until 1927 to do so again, this time for a regionally popular White evangelical preacher, the Rev. J.O. Hanes, from Birmingham. The third, and last portrait label, came out in 1928, purportedly to celebrate the birthday of the company’s bestselling bluesman, Blind Lemon Jefferson.

As a publicity tool, the use of portrait labels on 78s was fairly common among record companies in the 1920s and 1930s. What makes the three Paramount portrait labels stand out is the beauty, and the thoughtfulness that went into their design—characteristics, frankly, Paramount wasn’t generally noted for.

The fact that Paramount only produced three such records between 1924, when the “Ma” Rainey 78 came out, and 1932, when the company went under in the Great Depression, suggests that the use of portrait labels was a nice gimmick that didn’t necessarily increase record sales. Otherwise, there would have been more.

Today, copies of the issues are rare. The “Ma” Rainey 78s shows up at auction occasionally. Less frequently seen is the one for Blind Lemon Jefferson. As for the Rev. J.O. Hanes 78, sales of it must have been low in comparison to the other two, because today it is his record that surfaces most infrequently. Moreover, he was not invited back to the recording studio.

Paramount portrait labels and 78 sleeve graphics are from the Bowman collection.