“Mamie’s Blues”

Mamie Desdunes

1879-1911

She was good natured, a fine dresser, and extremely popular with the sporting crowd.

-Charles Edward Smith, quoting Jelly Roll Morton, 1940

She was pretty good looking—quite fair and with a nice head of hair. She was a hustling woman. A blues-singing poor girl. Use to play a pretty fair piano in those dance halls on Perdido Street. When Hattie Rogers or Lulu White would put it out that Mamie was going to be singing at her place, the white men would turn out in bunches and the whores would clean up.

–Bunk Johnson, 1949

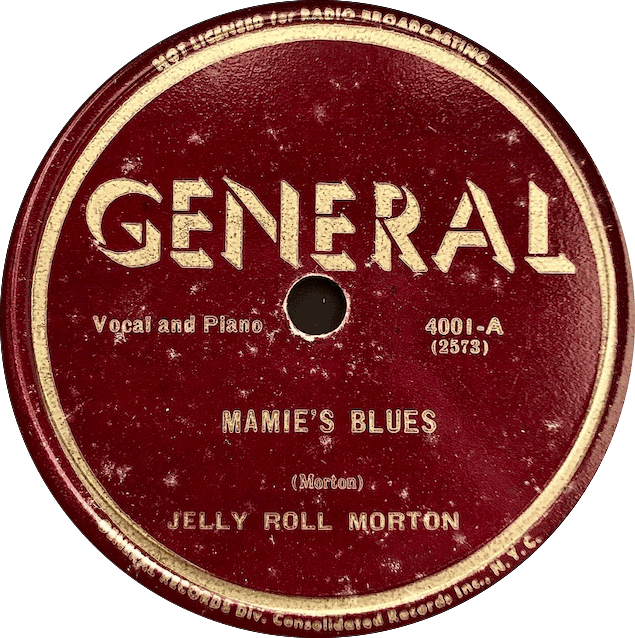

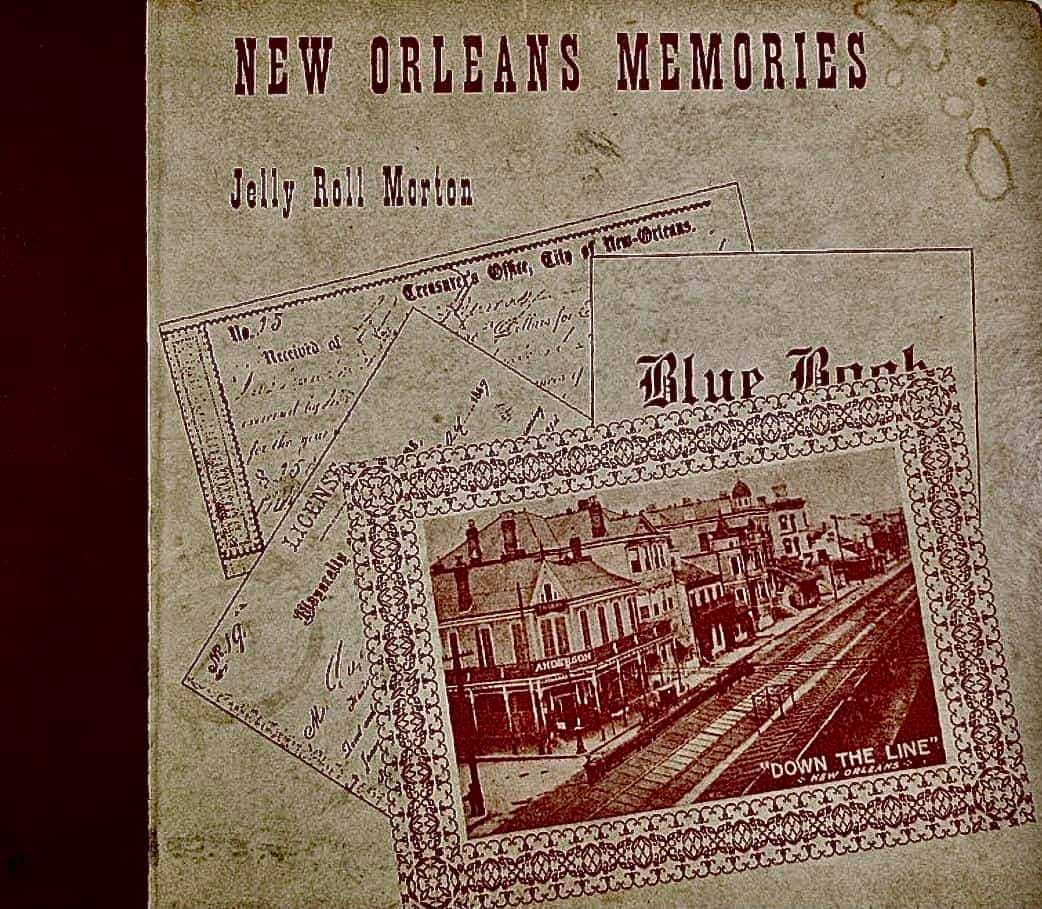

On December 16, 1939, Jelly Roll Morton recorded in New York City a song to be part of a collection of musical pieces that General Records would release as an album of 78 rpm records entitled New Orleans Memories.

In the recording studio it was only Morton and his piano, just like it had been in the beginning when he was a teenager playing piano in the brothels of Storyville, New Orlean’s legally-sanctioned red light district. This particular song had been around for ages and was usually called the “219 Blues”.

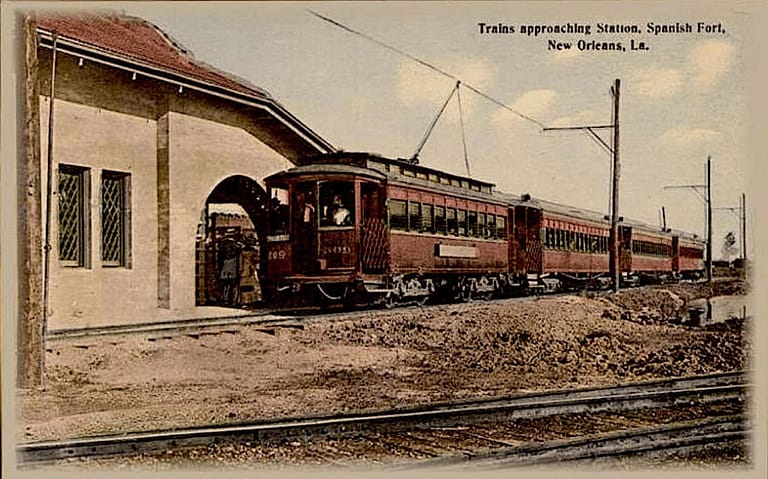

Morton explained that the 219 was the train that “took the gals out on the T&P [Texas and Pacific railroad] to the sporting houses on the Texas side of the circuit… [and] the 217 on the S.P. [Southern Pacific] through San Antonio and Houston brought them back to New Orleans.” This is actually one of the earliest Blues songs. Morton chose to call it “Mamie’s Blues” after the woman he learned it from, Mamie Desdunes.

That was a wise decision.

This is the first Blues I no doubt heard in my life. Mamie Desdunes, this is her favorite Blues. She could hardly play anything else more, but she really could play this number. Of course, to get in on it, to try to learn it, I made myself the “can rusher”.

“Can rusher”? In the early 1900s in New Orleans before beer was sold in bottles teenage boys were paid to take empty buckets and cans to the saloon to fill with beer, and then haul back for thirsty drinkers—hence the song from that time period, “My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It”.

For many listeners, “Mamie’s Blues” by itself is worth the price of admission to “New Orleans Memories”. Since 1940, music commentators have singled out the song for its haunting qualities. Once you hear Jelly Roll Morton sing “Mamie’s Blues”, you won’t forget it. His interjection, “Her ‘feets’ was wet”, can break your heart.

Morton’s biographer William J. Schaffer sums it up best: “The single track justified the the whole set of recordings … [it being] as simple and inexhaustible as a haiku ….”

For many listeners perhaps part of the mystique of the song was the mystery of Mamie Desdunes, herself. Who was this woman?

Once, we knew very little about her except for the few clues Morton threw out during the song.

Today, fortunately, we have some concrete facts as to Desdunes’ life, along with reasonable conjectures that come with them. New information has been gleaned from various sources, including census records, newspaper articles, New Orleans street directories, and rediscovered old interviews with jazzmen who were Mamie’s contemporaries.

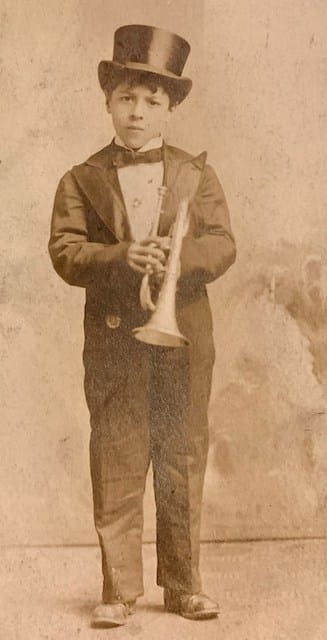

We know for example that Mamie was born “Mary Celina Desdunes” in New Orleans in 1879, to Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes, a prominent Black Creole politician and writer, and to Clementine Walker, her father’s Black mistress. The couple would have four children together, with Mamie being the eldest. Her half-brother Daniel, from the legitimate side of the family, was a well-known New Orleans musician and bandleader.

Clementine died when Mamie was twelve, and she was raised by her grandmother. How much interaction Mamie had with her father we don’t know. Given the long-term relationship between Rodolphe and Clementine, there must have been contact between father and daughter.

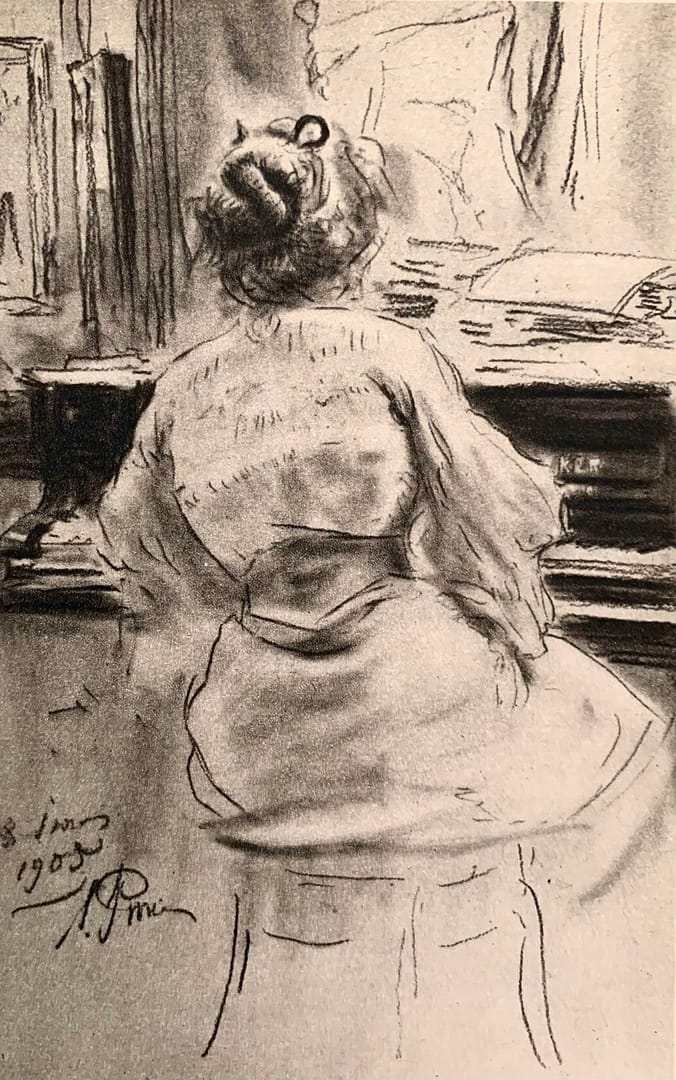

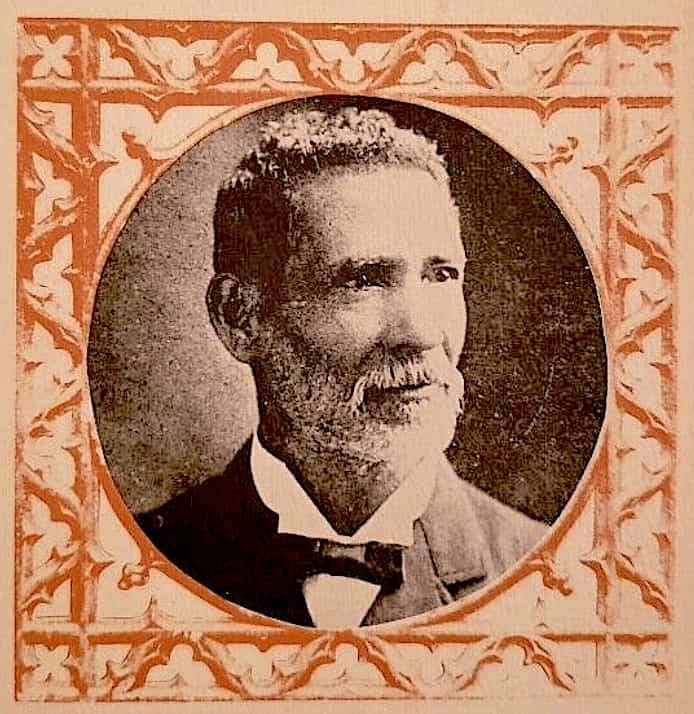

Mamie Desdunes’ father Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes (1849-1928).

We know for example that Mamie was born “Mary Celina Desdunes” in New Orleans in 1879, to Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes, a prominent Black Creole politician and writer, and to Clementine Walker, her father’s Black mistress. The couple would have four children together, with Mamie being the eldest. Her half-brother Daniel, from the legitimate side of the family, was a well-known New Orleans musician and bandleader.

Mamie Desdunes’ father Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes (1849-1928).

Clementine died when Mamie was twelve, and she was raised by her grandmother. How much interaction Mamie had with her father we don’t know. Given the long-term relationship between Rodolphe and Clementine, there must have been contact between father and daughter.

Pronouncing “Desdunes”.

Mamie Desdunes, like Jelly Roll Morton, was descended from French Haitian Creoles who fled the Haitian Revolution in the early 1800s. The Desdunes family carried to New Orlean their French heritage in the form of both customs and language. The French pronunciation of Desdunes is “day-doon”. Yet Morton, who grew up in French-speaking homes doesn’t pronounce it that way. He seems to be saying “dez-doon”. Perhaps the pronunciation of the Desdunes name had already been corrupted by Southern speakers by the time Morton came along and he was simply following suit. Whatever the reason for the change, his take on the name sounds charming.

We know that Mamie married warehouse worker George Dugue (Degay) from Mississippi about 1898. We also know that she was living with him in 1900, but seemed to be living separately from him in the years she worked in Storyville. Apparently she reconciled with him before her death at home from tuberculosis in 1911.

We know that when Mamie was fourteen she was returning home from a family picnic at Spanish Fort on Lake Pontchartrain, and while attempting to jump onto a moving train was run over, suffering a fractured leg and the ultimate amputation of two fingers on her right hand.

In addition to playing piano in the Storyville whorehouses, in all likelihood Mamie worked as a prostitute herself, at least at times, perhaps a reason for the separation with her husband. One musician who regularly played piano in “The District” back in the day, Manuel Manetta, remembered that she had actually worked as a madam in one of the smaller brothels. In a 1908 City directory her occupation was listed as that of “seamstress”. But, in this era, many women who worked in the prostitution trade labeled themselves as “seamstresses” as cover for their real occupations.

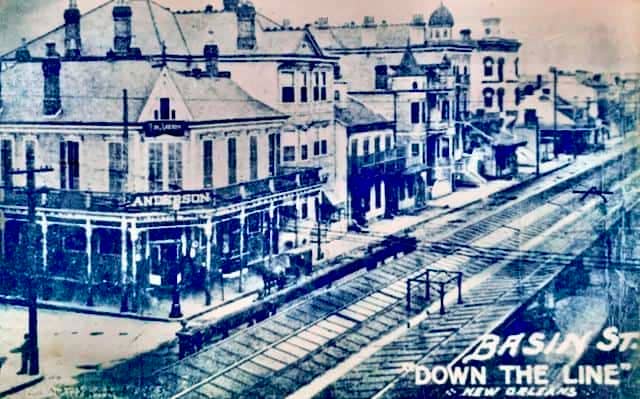

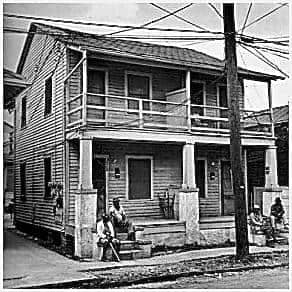

One of the few photographs of Storyville, this one from about 1908.

Finally, we know that at some point Mamie resided in the Garden District as a neighbor of Jelly Roll Morton’s godmother with whom he lived much of his teenage years in New Orleans. There were past connections between the two families. There is no doubt that he knew Desdunes well and that she opened doors for him.

Mamie would be the “older” woman in Morton’s life. Morton claimed to be born in 1885, but scholars believe he was born in 1890, meaning there was a 5-10 year age difference. There is no doubt that he knew Desdunes well. It’s possible that Mamie helped the young man initially find work playing piano in some of the same Storyville whorehouses where she worked. It may not have been a coincidence that both played piano at Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall, perhaps the most famed establishment in “The District”.

Mamie Desdunes’s house at 2328 Toledano Street. By street car, it was about two miles from Storyville.

Mamie was known to host parties at her house for fellow Storyville pianists—now forgotten names such as Buddy Carter, Joyce Adams, and Kid Game—and these may been opportunities for the young Morton to establish other contacts at Storyville. Morton never mentioned this. On the other hand, he never mentioned Mamie playing piano in the brothels. Despite his jobs in Storyville, his work as a pimp, and his helping manage whorehouses in Nevada and California, Morton always had old-fashioned attitudes towards sex, and was very protective to women with whom he was close. The most he would say about Mamie is that she ran with the “sporting crowd”.

Mamie was known to host parties at her house for fellow Storyville pianists—now forgotten names such as Buddy Carter, Joyce Adams, and Kid Game—and these may been opportunities for the young Morton to establish other contacts at Storyville. Morton never mentioned this. On the other hand, he never mentioned Mamie playing piano in the brothels. Despite his jobs in Storyville, his work as a pimp, and his helping manage whorehouses in Nevada and California, Morton always had old-fashioned attitudes towards sex, and was very protective to women with whom he was close. The most he would say about Mamie is that she ran with the “sporting crowd”.

Mamie Desdunes’s house at 2328 Toledano Street. By street car, it was about two miles from Storyville.

The difference in styles between the two entertainers would have been obvious: while both sang dirty lyrics for male patrons in keeping with the ambiance of a brothel, Morton was also a hotshot pianist who could play instrumentals fast and furious, while Desdunes, because of her missing fingers, concentrated on slower pieces such as Blues, and emphasized her singing. If Bunk Johnson’s assessment of her popularity is correct, surely the patrons where she played didn’t mind.

For an absorbing on-line visit to the world of Storyville, please check out The Historic New Orleans Collection at this link:

If we can’t always see Desdunes clearly in the darkness of the past, at least now we can focus on the broad outlines of her life. If we squint our eyes, she will come into view for a few seconds. She was a talented Black woman, who, in her short life span, lived a full life on her own terms and influenced the musical ambitions of a teenager named Ferdinand Joseph Lamothe, later known as Jelly Roll Morton.

The exact extent of the relationship between Desdunes and Morton, piano teacher and pupil—or perhaps more —we will never know. But it transcended mere friendship.

Towards the end of Jelly Roll Morton’s recording of “Winin’ Boy Blues” for the General Records session, Morton moans, “Oh ____!”, the last word not being clear in the recording itself. Charles Edward Smith who was at the recording session heard him moan: “Oh Mamie!” Almost forty years later, she was still on his mind.

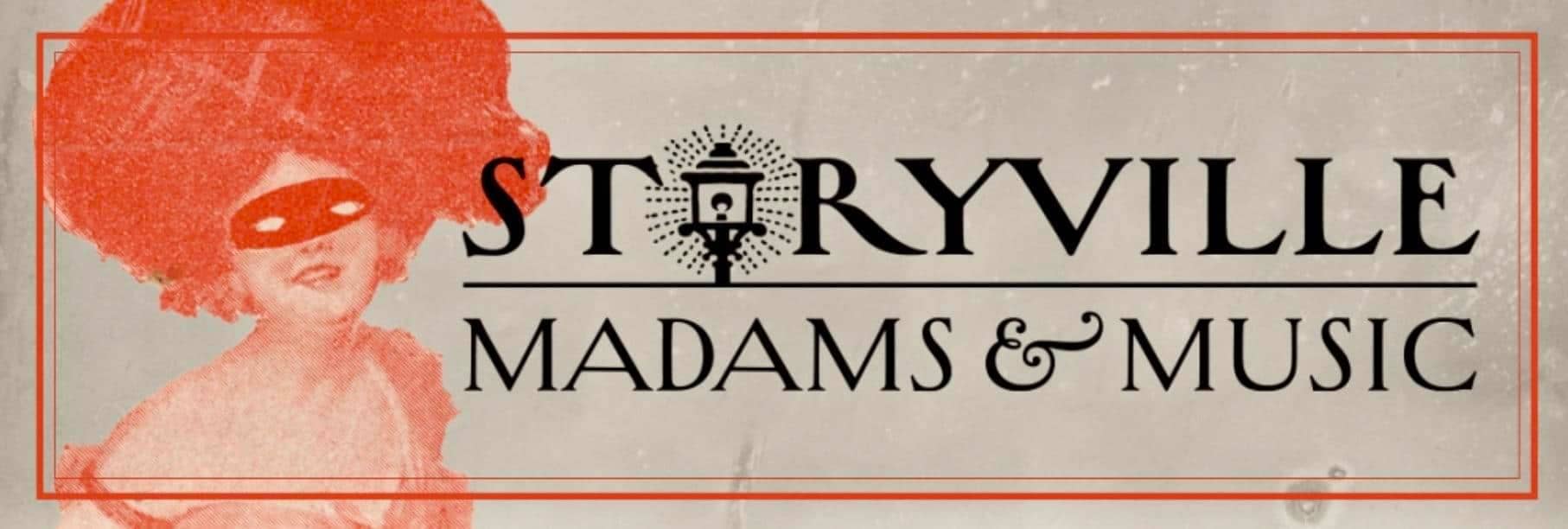

Some of the music that Jelly Roll Morton recorded for the “New Orleans Memories” album he had already released numerous times since 1923, on 78 rpm records, transcription discs, and piano rolls, both as solo and band pieces. But he only recorded “Mamie’s Blues” twice, once for the Library of Congress in 1938, and later for General Records in 1939. As will be heard, the two versions are quite different.

In the Library of Congress version of the song, Morton adds more sexually suggestive verses such as, “I’ve got a husband, I’ve got a kid man too.” For Mamie, the kid man, “looks like he sets my natural soul free.” It’s understandable as to why Morton didn’t use such verses on his later commercial recording.

There are two distinct piano styles between the two versions. Morton uses his more ornate “Spanish-tinged” piano style for the Library of Congress recording, while he played a simpler, Blues-style piano on “New Orleans Memories”. This begs the question: which was the version he learned as a boy from Mamie Desdunes? It is probable that Desdunes, who was acknowledged as a Blues singer and not a jazz musician, stuck closer to the simpler style that Morton played for General Records. Further, with two fingers missing, it would have been difficult for her to incorporate Morton’s Spanish-tinged elements.

Mamie’s Blues

Jelly Roll Morton

Library of Congress recording

Washington D.C., May-July, 1938

Mamie’s Blues

Jelly Roll Morton

General Records 4001

New York City, December 18, 1939

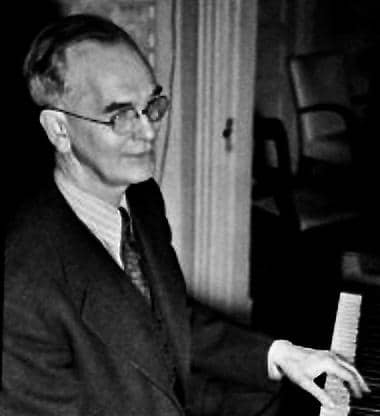

Jelly Roll Morton was a great composer, musician, bandleader, and raconteur, but a famously poor businessman. Many songwriters and composers suffered at the hands of the publishing companies in the 1920s and 1930s, but Morton particularly so.

Although Morton complained to whoever would listen that publishers stole payments and royalties for his music, in reality it was at least partially his own fault because he didn’t pay close attention to details in the contracts he signed. Except in music itself Morton was never a “detail man”. This was not so much a worry during flush times when money was flowing in. But the Great Depression and changes in musical tastes ended those good times for Morton, and by the General Records session he was drawing limited royalties, and, being strapped for cash, he was pawning his few remaining assets.

Fortunately for Morton he was befriended by Roy Carew, a businessman who had worked in New Orleans in the early 1900s and had fallen in love with the City’s jazz music. Carew would not meet Morton until 1938, when the down-on-his-luck musician was playing piano at a small club in Washington D.C., where Carew was then living.

Early in the friendship, Carew assisted Morton—unsuccessfully, it turned out—in trying to get back-payments owed Morton by his early publishers. More successfully, Carew and Morton started the Tempo Music Publishing Company in order to protect Morton’s future interests in music recorded in the Library of Congress and General Records sessions. Carew ran the company out of his home.

Below is the 1948 edition of Tempo’s “Mamie’s Blues”, complete with the lyrics sung by Jelly Roll Morton for General Records. Sadly, Morton died before this came out.

This rare piece of sheet music was originally in the collection of music historian Rudi Blesh, co-author of They All Played Ragtime.

In copywriting “Mamie’s Blues” in 1939 and 1940, Morton could have claimed for himself authorship of the song–afterall, General Records had listed Morton as the composer on the record label. But he didn’t. Following the General Records session, Morton wrote a letter to Roy Carew regarding copyright matters for “Mamie’s Blues”, wanting to ensure that Desdunes got credit for the song:

Mamie Desdune(s) wrote “Mamie’s Blues” in the late 90s. I don’t like to take credit for something that don’t belong to me. I guess she’s dead by now & there would probably be no royalty to pay, but she did write it.

Thanks to Morton the song “Mamie’s Blues” would always belong to Mamie Desdunes.

Ironically, in the year before Morton died in 1941, Carew was now having to assist him in attempts to also pry royalty payments out of General Records for “Mamie’s Blues” and the other music he had recorded for the company.

When the thirty-two year old Mamie Desdunes died in New Orleans of tuberculosis in 1911, Morton, long gone from the City, was a little-known entertainer traveling the country in search of fame and fortune, the first which he eventually clinched, while to his horror he would watch the second slip through his fingers.

At the time of her death, Mamie was only a fringe figure in the history of Storyville. Soon she would be forgotten altogether. But in time she would be brought back to life and immortalized by the boy she taught to play Blues piano, and who as a man recorded “Mamie’s Blues”.

There is one other glimpse of Mamie, a sad one if true. In researching his biography of Jelly Roll Morton, Alan Lomax found himself going through a family photograph album with Danny Barker, New Orleans musician and jazz historian. Barker came from an old New Orleans family, many members being prominent musicians. In fact, Barker grew up in the same ward as Jelly Roll Morton; he would later play banjo in Morton’s band. As Lomax remembered, Barker pointed to the faded photograph of a “sweet-faced Creole girl”:

There is one other glimpse of Mamie, a sad one if true. In researching his biography of Jelly Roll Morton, Alan Lomax found himself going through a family photograph album with Danny Barker, New Orleans musician and jazz historian. Barker came from an old New Orleans family, many members being prominent musicians. In fact, Barker grew up in the same ward as Jelly Roll Morton; he would later play banjo in Morton’s band. As Lomax remembered, Barker pointed to the faded photograph of a “sweet-faced Creole girl”:

That’s Mamie Desdoumes, a cousin of mine. That’s what she looked like before that pimp got hold of her. She was the family darling. Then she disappeared. He had taken her out of town. Then later he put her to work for him in one of those houses in Storyville. They often held the girls against their will. Well, Mamie tried to escape one night. She jumped out of a second-story window and broke her hip, so that she was always deformed after that. Then she couldn’t get away. Later she became famous for the blues.

Perhaps it was then that she began to sing:

Two nineteen done took my baby away

Two nineteen took my babe away

Two seventeen bring her back someday

Stood on the corner with her feets just soakin’ wet

(Her feets was wet)

Stood on the corner with her feet soakin’ wet

Beggin’ each an’ every man that she met

If you can’t give a dollar, give me a lousy dime

Can’t give a dollar, give me a lousy dime

I want to feed that hungry man of mine

Photos of Mamie Desdunes’ house, Roy Carew, and Danny Barker are from the internet. All other photos and ephemera, including the “Mamie’s Blues” sheet music, are from the Bowman collection.