FREDDIE KEPPARD

“Walk It Sweet Mamma That’s All”

To be [a musician who is] remembered past one’s time requires the further assistance of one’s musical children and grandchildren, of recordings, critics, collectors, scholars, and, in general, the simplifying myths which allows us to live with the past.

Lawrence Gushee

I never heard a man that could beat Keppard—his reach was so exceptional—both high and low, with all degrees of power, great imagination, and more tone than anybody, . . .

[Freddie Keppard’s] Creole Band was tremendous. They really played jazz.

Jelly Roll Morton

It’s the 4th of July, 1913. Buddy Bolden, the first “King” of the cornet in New Orleans, has been in the insane asylum for the past six years. Joe Oliver, polishing his cornet, is waiting on the sidelines to seize the “King’s” crown for himself.

A young Buddy Bolden, about 1894-1895.

The Original Olympia Jazz Band, after five years in existence, is still one of the best Black bands in New Orleans, playing both sweet dance numbers, as well as the hot, “ratty” style music that “King” Bolden pioneered. The Olympia band is looking to the future, already advertising itself as a “jazz” band, rather than a staid novelty or ragtime group. Good marketing!

And Freddie Keppard—now “King” Keppard, Bolden’s successor and current leader of the Olympia band—is uneasily trying to hold on to Bolden’s old crown.

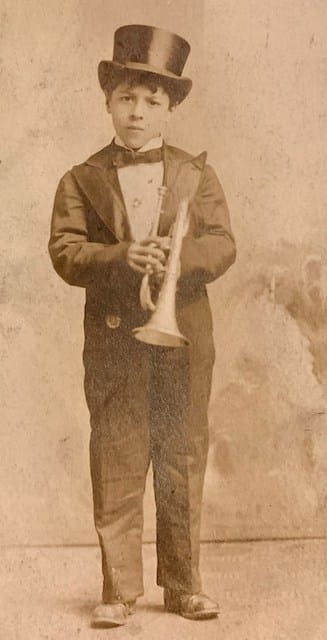

A candid photo of a young Freddie Keppard from about 1913. The uniform suggest that it was taken in New Orleans, where band members often wore uniforms, a spillover from the 1800s.

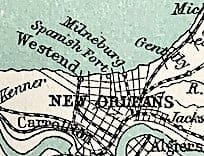

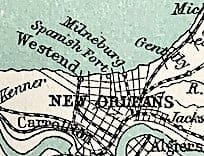

Milneburg, one of the resort communities on Lake Pontchartrain close to New Orleans, becomes alive on weekends and holidays. Trains run from downtown to the lake shore. Buildings erected on piers are rented out for fishing parties, picnics, and family or club gatherings.

A candid photo of a young Freddie Keppard from about 1913. The uniform suggest that it was taken in New Orleans, where band members often wore uniforms, a spillover from the 1800s.

Milneburg, one of the resort communities on Lake Pontchartrain close to New Orleans, becomes alive on weekends and holidays. Trains run from downtown to the lake shore. Buildings erected on piers are rented out for fishing parties, picnics, and family or club gatherings.

Music from New Orleans bands is a constant in Milneburg, as well as nearby Spanish Fort and Westend. Black bands play for Black audiences and White bands play for White audiences, but once music escapes its confines it pollinates all bands in the vicinity, with White and Black musicians picking up sounds and styles from one another. And as music is wafting in the air, vendors are moving through the crowds selling beer and food.

Keppard and his band are regular performers at Milneburg picnics on Saturdays and Sundays, as well as holidays. In fact, Keppard has been playing in bands at Milneburg since he was a young boy playing guitar.

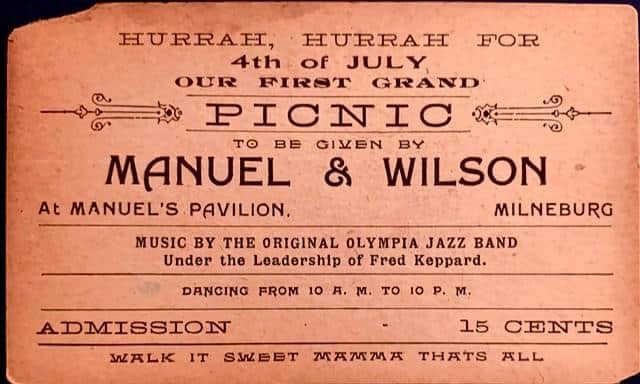

Sometimes the Olympia band is booked in advance like for this Fourth of July engagement at Manuel’s Pavilion. Tickets are printed. Other times the

Keppard and his band are regular performers at Milneburg picnics on Saturdays and Sundays, as well as holidays. In fact, Keppard has been playing in bands at Milneburg since he was a young boy playing guitar.

band shows up and starts playing off the boardwalk, near where passengers disembark from the trains. Then if people like the sound they will hire the Olympia band for their picnic. As many as twenty to thirty bands might be playing at Milneburg on a given day.

Sometimes the Olympia band is booked in advance like for this Fourth of July engagement at Manuel’s Pavilion. Tickets are printed. Other times the band shows up and starts playing off the boardwalk, near where passengers disembark from the trains. Then if people like the sound they will hire the Olympia band for their picnic. As many as twenty to thirty bands might be playing at Milneburg on a given day.

Twenty-three-year old Keppard and his Original Olympia Jazz Band are accustomed to nighttime performances, so to play a twelve-hour engagement —only 15 cents for twelve hours of great music!—starting at 10 o’clock in the morning can be a challenge, especially with the rising Louisiana heat and humidity. Note: 15 cents in 1913 would be the equivalent of $4.50 today.

Frederick Keppard was born February 27, 1890, near what would soon become New Orleans’ legalized red-light district, Storyville. Keppard is a light-skinned Black Creole, proud of his French heritage. He uses the French pronunciation of his name with the silent “d”. French is his first language and he will retain a Creole accent for the rest of his life. In New Orleans he is called “Fred”.

Keppard doesn’t walk, he struts; wearing the best suits, he commands attention. He is often called “haughty” by his peers. He is funny and talks very loudly. Sometimes he is deemed “lazy”. At times his overconsumption of alcohol leads to clowning on stage although audiences seem to like this. Unlike many contemporaries, Keppard doesn’t work a day job. He just makes music. He moves through life at his own speed and seems to answer to no one.

A photo of Freddie Keppard showing him at his first communion at age ten. In his youth, boys in New Orleans dressed in short pants. His older brother Louis, who also became a musician and band leader, remembered that because children were not allowed in the Storyville District, in order to fool the police when they visited he and Freddie would find long pants to wear. Then to legitimize their purpose in Storyville they shined shoes while all the time absorbing the beautiful musical sounds spilling out of the buildings. This was to be Freddie’s real music education.

Even though he can’t read music at this stage of his career, Keppard is a man of immense talent on the cornet, and he knows it. His many fans know it, too. It was clear that once Buddy Bolden was gone that Freddie Keppard would inherit his crown, so he is now “King” Keppard. In fact, in addition to playing in the Olympia band, he sometimes plays in The Eagle Band, Buddy’s old band. But being “King” may not last, New Orleans being so full of wonderful horn players eager to move up.

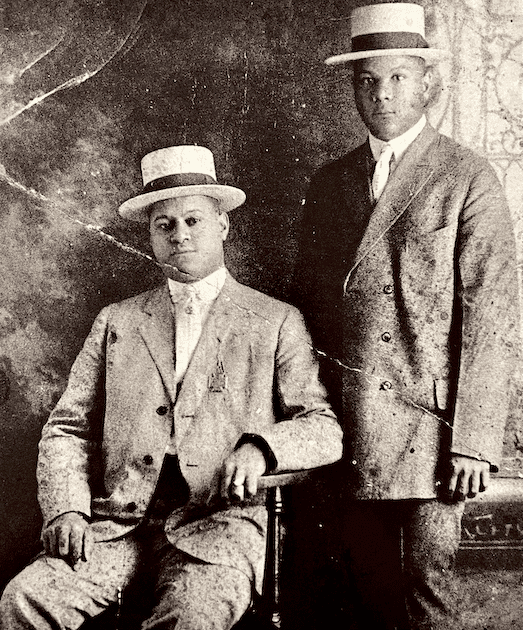

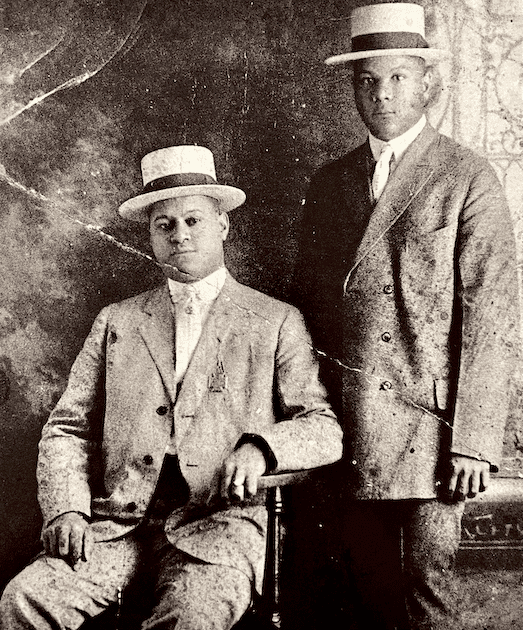

The two well-dressed young men are Freddie Keppard (seated) and his younger New Orleans friend Sidney Bechet, who will become one of the great jazz saxophonists. Lawrence Gushee and Dan Vernhettes suggest this was taken circa 1917-1918, but given the youthful appearances of both musicians, it is possible it was taken before Keppard left New Orleans in 1914.

As his band starts warming up on this 4th of July morning, Keppard does what he is doing more often these days. He reaches into his pocket for his flask of gin.

The two well-dressed young men are Freddie Keppard (seated) and his younger New Orleans friend Sidney Bechet, who will become one of the great jazz saxophonists. Lawrence Gushee and Dan Vernhettes suggest this was taken circa 1917-1918. But given the youthful appearances of both musicians, it is possible to have been taken before Keppard left New Orleans in 1914.

The motto at the bottom of the picnic ticket – -“Walk It Pretty Mamma That’s All” – – is, perhaps, a reflection on Freddie Keppard’s attitude towards life, his insouciance. He ranks the joys of living in the following order: music, alcohol, and women. In time, alcohol will gain the number one spot.

As his band starts warming up on this 4th of July morning, Keppard does what he is doing more often these days. He reaches into his pocket for his flask of gin.

The motto at the bottom of the picnic ticket – -“Walk It Pretty Mamma That’s All” – – is, perhaps, a reflection on Freddie Keppard’s attitude towards life, his insouciance. He ranks the joys of living in the following order: music alcohol, and women. In time, alcohol will gain the number one spot.

The faded picnic ticket is a unique look at a time and place that will soon vanish: that period in New Orleans when the saloons, clubs, and brothels of Storyville with their perfumed corruption provide musical venues for the city’s early jazz greats; and when notable jazz groups play for free on sidewalks, inside city parks, atop truck beds and wagons, and while marching in parades. It’s a time when most of the city’s jazz fathers have yet to hit the road to California and Chicago.

Soon they will. Soon Freddie Keppard will.

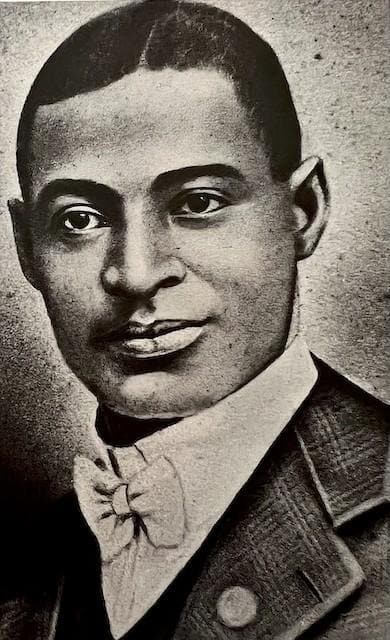

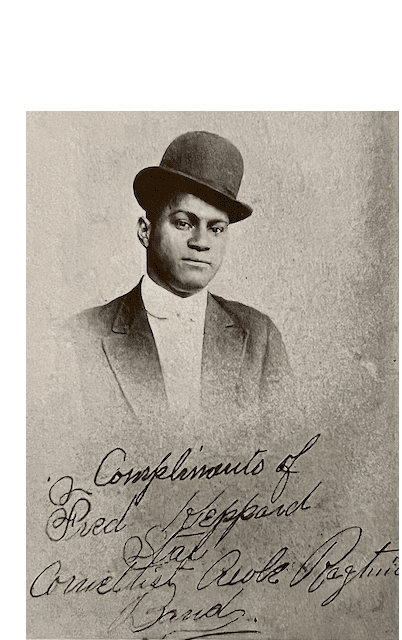

Another photo showing Freddie Keppard as a dapper dresser. Like the previous photo it may have been taken in New Orleans before he left for California. It’s likely that this is how Keppard looked at the time of the picnic at Manuel’s Pavilion in Milneburg.

Another photo showing Freddie Keppard as a dapper dresser. Like the previous photo it may have been taken in New Orleans before he left for California. It’s likely that this is how Keppard looked at the time of the picnic at Manuel’s Pavilion in Milneburg.

The ticket came from La Belle Nouvelle Antiques on Magazine Street in New Orleans. It was part of a collection of similarly faded jazz band tickets, the others being from the late 1910s. Unfortunately, the Keppard ticket is not dated by year although it must be earlier.

A good estimate as to when the picnic took place is 1913. By that time—given his stellar horn playing—Keppard had risen to a leadership role in the Olympia band, a group that had begun as a collective. It was also around 1913 that Joe Oliver bested Keppard in a musical “cutting contest” in Storyville, thereby being crowned as the new king, “King” Oliver. Also 1913 is the last 4th of July that Keppard lives in New Orleans, so the picnic can’t have occurred any later.

Joe Oliver in 1915, a couple of years after he bested Freddie Keppard in a “cutting contest” in Storyville, thereby claiming the title of “King”. Evidently Keppard didn’t carry a grudge because later he would play for “King” Oliver’s band in Chicago, anticipating the powerful second chair cornet role that Louis Armstrong would later fill in 1922.

In 1914 Keppard left New Orleans for good to play in California with the groundbreaking Original Creole Orchestra, a popular Vaudeville band that would introduce the new jazz sounds of New Orleans to much of the United States. Perhaps Keppard’s trip to California was also his abdication of his crown. Kings have to go somewhere when they are forced off their thrones.

Joe Oliver in 1915, a couple of years after he bested Freddie Keppard in a “cutting contest” in Storyville, thereby claiming the title of “King”. Evidently Keppard didn’t carry a grudge because later he would play for “King” Oliver’s band in Chicago, anticipating the powerful second chair cornet role that Louis Armstrong would later fill in 1922.

In 1914 Keppard left New Orleans for good to play in California with the groundbreaking Original Creole Orchestra, a popular Vaudeville band that would introduce the new jazz sounds of New Orleans to much of the United States. Perhaps Keppard’s trip to California was also his abdication of his crown. Kings have to go somewhere when they are forced off their thrones.

The remains of an early photo of the “Original Creole Orchestra“. This shot would be used for advertisements. Freddie Keppard is second from left, top row. Bass player Bill Johnson (far right, top row) founded the band, and when he later joined King Oliver he probably brought with him his old band’s name, resulting in one of the most famous band names of all time: “King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band. Ironically neither Johnson nor Oliver was a Creole.

As for the Original Olympia Jazz Band, by the late 1910s it was led by famed bandleader and music publisher A.J. Piron. So if the picnic ticket was really from that later period it would read that the band was “under the direction of A.J. Piron”. Not Keppard.

Like Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver, once Keppard left New Orleans and its oppressive racism he would never return home, although he would keep his legal address at his mother’s house when he was on the road. The South was too dangerous for a Black man with his talent and temperament. Keppard would spend the next four years touring with the Original Creole Orchestra, traveling up and down the West Coast, into Canada, down the East Coast, and into the Midwest.

“Big Eye” Louis Nelson DeLisle (seated) and Freddie Keppard about 1917 while members of the “Original Creole Band”. Did Keppard really play the small slide cornet? Maybe. Horn maker C.G. Conn advertised the instrument for Vaudeville and jazz bands, because of its “startling glissando and novelty effects.”

Notice that Freddie Keppard bills himself as the “Star Cornetist ‘Creole Ragtime Band’”. The name of the “Original Creole Band” was modified from time to time. Keppard liked wearing derbies, because he could use them as cornet mutes.

The wear and tear of being on the road constantly, plus Keppard’s increased drinking and his growing unreliability, broke up the band in Chicago in 1918. Keppard decided to stay. He married Saraphine “Sadie” Campbell from New Orleans, and made Chicago his home for the next fifteen years. Until health problems ended his music career by 1931, Keppard performed in numerous bands in the Chicago area. In fact in 1920 Keppard briefly played in King Oliver’s band in Chicago. Two “Kings” on the same stage!

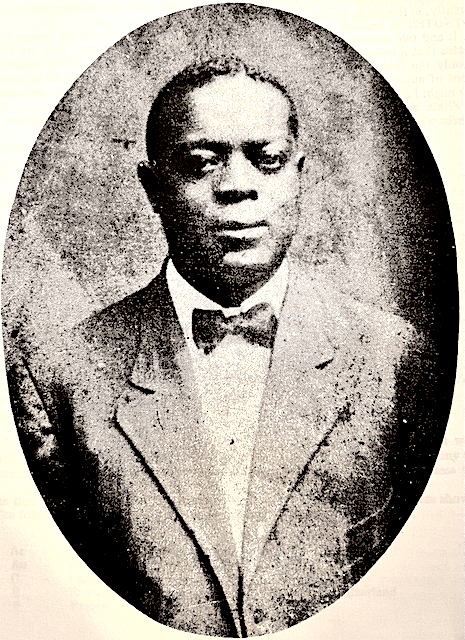

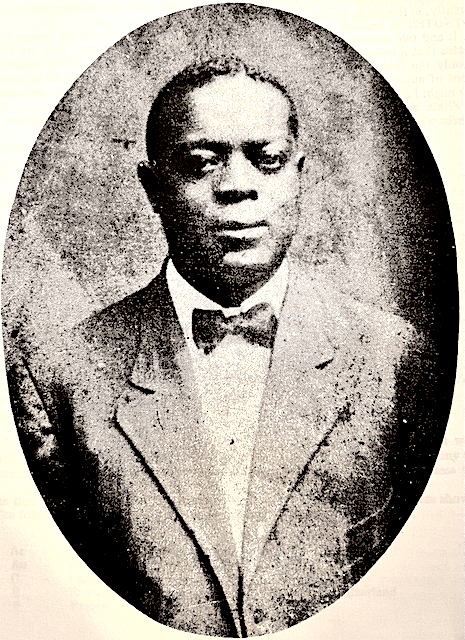

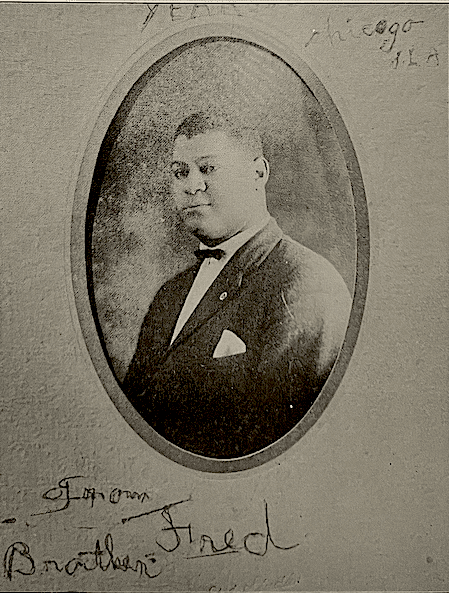

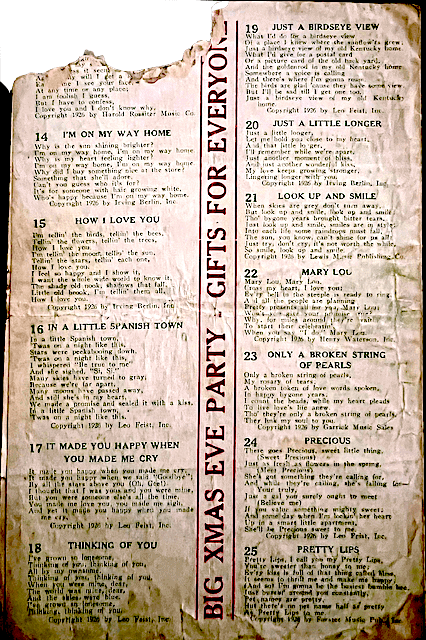

It’s not clear if this is a photo that Freddie Keppard sent to his brother Louis from Chicago when he was still in the “Original Creole Band” or if this studio portrait was taken after the breakup of the band. This appears to be a slightly older Keppard after he had relocated to Chicago.

The big question puzzling 78 record collectors and jazz historians has long been what Freddie Keppard sounded like in his formative years in New Orleans such that he would be crowned “King” in his late teens. What, in fact, did he sound like playing with the Olympia band performing on the Fourth of July? Was he really that great? Some contemporaries, like Sidney Bechet and Jelly Roll Morton, said yes. Others, like Louis Armstrong, said no.

It’s not clear if this is a photo that Freddie Keppard sent to his brother Louis from Chicago when he was still in the “Original Creole Band” or if this studio portrait was taken after the breakup of the band. This appears to be a slightly older Keppard after he had relocated to Chicago.

Stories have long circulated that a record company—perhaps Victor, the largest record company of the day—approached the Original Creole Orchestra in 1916. There are a number of versions about why Keppard declined to go into the recording studio for an historical event, the making of the very first jazz record. One story relates that when told the recording fee for the band would only be $25, Keppard laughed: “Hell! I drink that much gin in a day!”

The big question puzzling 78 record collectors and jazz historians has long been what Freddie Keppard sounded like in his formative years in New Orleans such that he would be crowned “King” in his late teens. What, in fact, did he sound like playing with the Olympia band performing on the Fourth of July? Was he really that great? Some contemporaries, like Sidney Bechet and Jelly Roll Morton, said yes. Others, like Louis Armstrong, said no.

Stories have long circulated that a record company—perhaps Victor, the largest record company of the day—approached the Original Creole Orchestra in 1916. There are a number of versions about why Keppard declined to go into the recording studio for an historical event, the making of the very first jazz record. One story relates that when told the recording fee for the band would only be $25, Keppard laughed: “Hell! I drink that much gin in a day!”

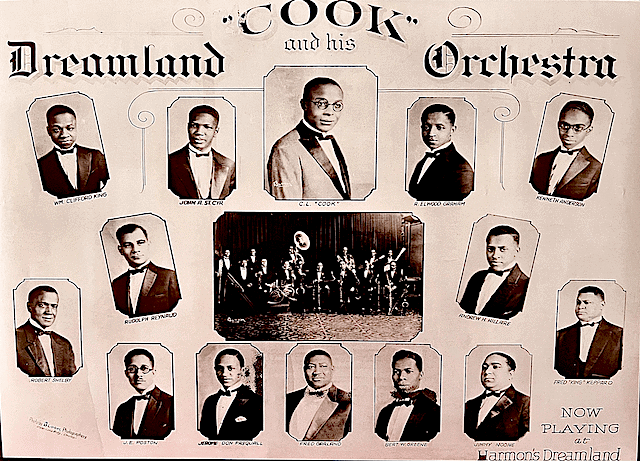

Keppard finally did record in the 1920s: first with Erskine Tate’s Vendome Orchestra in 1923; and later with “Doc” Cook’s various bands between 1924 and 1926. These were examples of the best Chicago Black dance bands of the day. He may have even recorded with a couple of other bands, but no one is positive.

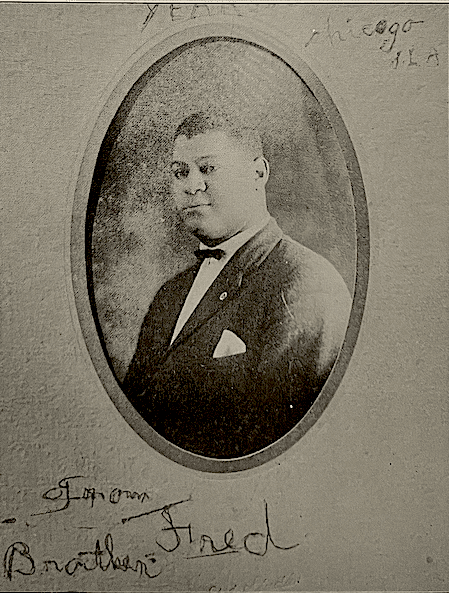

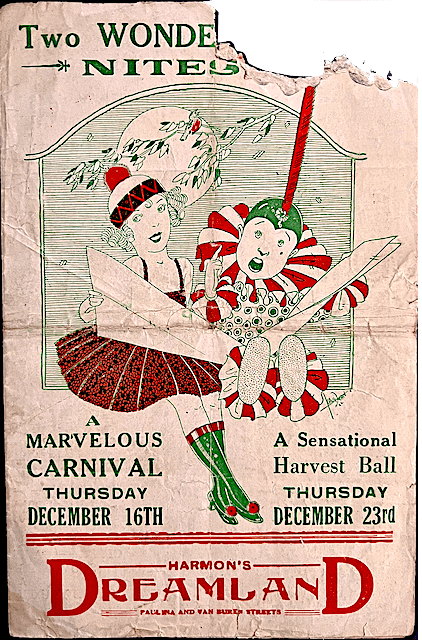

Keppard never stayed long in any Chicago band in the 1920s, but he did seem to have a preference for Charles L. “Doc” Cooke’s band, Cook and his Dreamland Syncopators (Orchestra), a sometimes “jazzy” band that played for White audiences as the house band at Harmon’s Dreamland Ballroom. He played for Cooke at various times between 1924 and early 1927, and was likely playing with the band at the two special events advertised below.

“Doc” Cooke had a college degree in music and filled his dance bands with some of the best jazz players of the day. Most of his band arrangements were written scores, but Keppard was the exception, and Cooke left it to him to improvise his assigned measures.

Oldtimers who remembered the young Freddie Keppard in New Orleans could not reconcile their memories with the new sounds heard on the records of Vendome Orchestra and “Doc” Cooke’s bands. Was that really Keppard? They often attributed the perceived change to Keppard being past his prime and in deteriorating health.

Keppard’s music on these 78 records is, in fact, excellent for what it was: second chair cornet solos adding brief jazzy filagrees to the music, a role much like that later performed by Bix for the Whiteman band. But we recognize Bix’s greatness because we have also heard him on 78 records when he is let loose and leading his own groups. That’s not the case with Keppard. With these 78s he is playing the role of a company man.

Perhaps one reason Freddie Keppard enjoyed playing with “Doc” Cooke’s band was because it reunited him with his old buddy from New Orleans, Jimmie Noone. Noted for his smooth clarinet style, Noone was on the verge of emerging as one of the most popular Black dance band leaders for White audiences in Chicago with his Apex Club Orchestra, and in the process becoming an important recording artist for the Vocalion label. Aside from both musicians being from New Orleans and roughly the same age, their other connection was that Keppard and Noone’s sister had lived together in the Crescent City.

Perhaps one reason Freddie Keppard enjoyed playing with “Doc” Cooke’s band was because it reunited him with his old buddy from New Orleans, Jimmie Noone. Noted for his smooth clarinet style, Noone was on the verge of emerging as one of the most popular Black dance band leaders for White audiences in Chicago with his Apex Club Orchestra, and in the process becoming an important recording artist for the Vocalion label. Aside from both musicians being from New Orleans and roughly the same age, their other connection was that Keppard and Noone’s sister had lived together in the Crescent City.

The closest we have to what Keppard sounded like in his early days in New Orleans is on only one record, this one made in 1926 for the Paramount Record Company. We are lucky to have it.

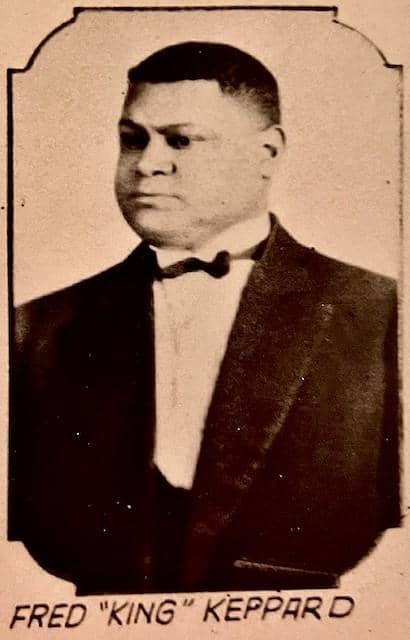

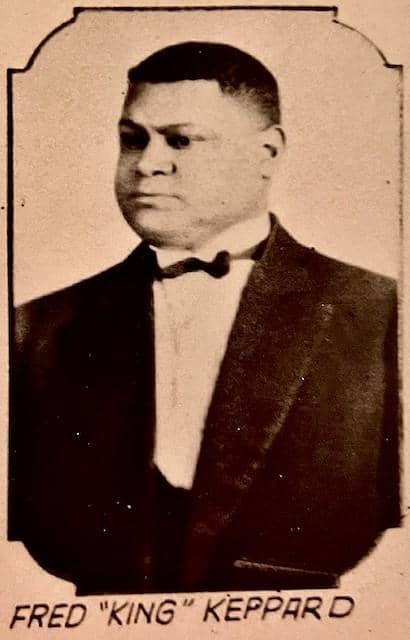

This photograph was probably taken close to the time that Freddie Keppard went into the Paramount studio in 1926. Keppard often looked self-assured, even cocky in earlier photos. But here he seems pensive. He is already starting to put on weight, and is probably beginning to realize that he’s facing serious health issues.

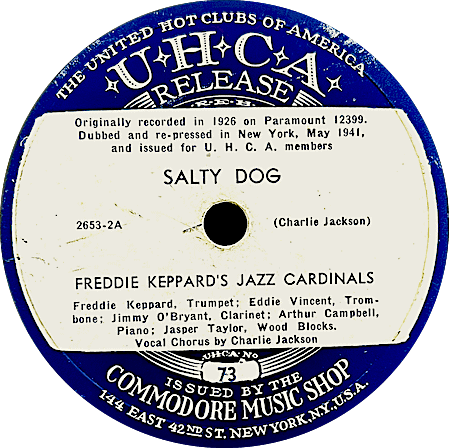

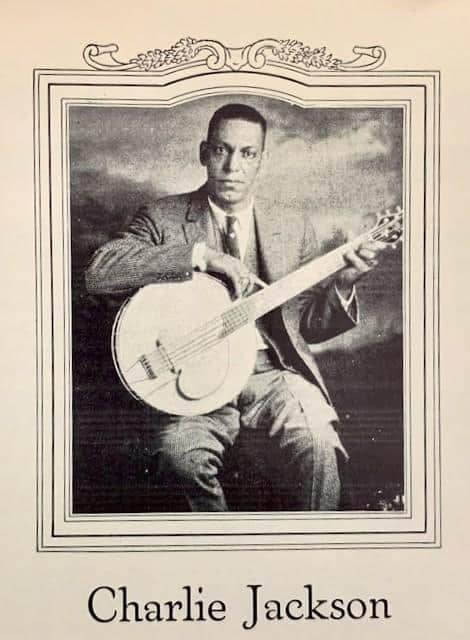

Like the other records he played on, this session was held in Chicago. Unlike the other ones, however, rather than playing with Northern musicians this time Keppard was re-united with fellow New Orleans friends: Johnny Dodds, clarinet; “Papa” Charlie Jackson, vocals; and Eddie Vincent, trombone—Vincent had been a fellow member of the Original Creole Orchestra; plus two non-New Orleans musicians, Jasper Taylor on wood blocks, and Arthur Campbell on piano.

This photograph was probably taken close to the time that Freddie Keppard went into the Paramount studio in 1926. Keppard often looked self-assured, even cocky in earlier photos. But here he seems pensive. He is already starting to put on weight, and is probably beginning to realize that he’s facing serious health issues.

Like the other records he played on, this session was held in Chicago. Unlike the other ones, however, rather than playing with Northern musicians this time Keppard was re-united with fellow New Orleans friends: Johnny Dodds, clarinet; “Papa” Charlie Jackson, vocals; and Eddie Vincent, trombone—Vincent had been a fellow member of the Original Creole Orchestra; plus two non-New Orleans musicians, Jasper Taylor on wood blocks, and Arthur Campbell on piano.

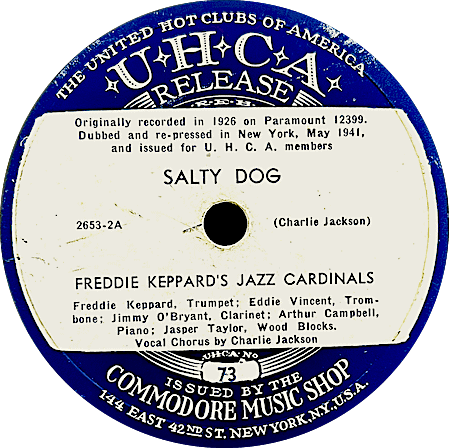

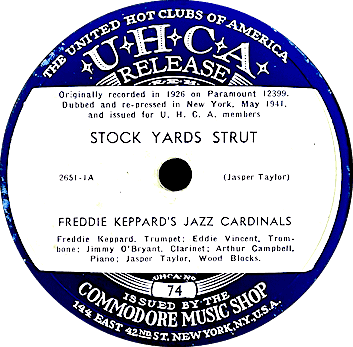

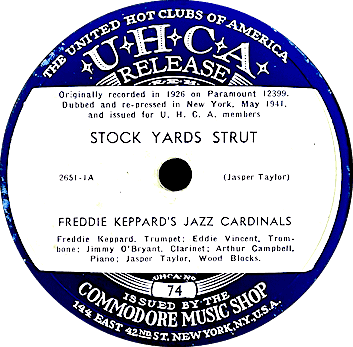

Issued by Paramount as “Freddie Keppard and His Jazz Cardinals”, this is the only record Keppard made under his own name. The two sides are “Stock Yards Strut”, and the perennial favorite, “Salty Dog”.

Reissue from 1940s of Take 1 of “Salty Dog”.

Reissue from 1940s of Take 1 of

“Salty Dog”.

Reissue from 1941 of Take 2 of “Salty Dog”. The label mistakenly shows Jimmy O’Bryant on clarinet instead of Johnny Dodds.

Reissue from 1941 of Take 2 of “Salty Dog”. The label mistakenly shows Jimmy O’Bryant on clarinet instead of Johnny Dodds.

Reissue from 1941 of “Stock Yards Strut”. Only one take was made of this tune. The label mistakenly shows Jimmy O’Bryant on clarinet instead of Johnny Dodds.

Reissue from 1941 of “Stock Yards Strut”. Only one take was made of this tune. The label mistakenly shows Jimmy O’Bryant on clarinet instead of Johnny Dodds.

Both Keppard and singer Charlie Jackson no doubt remembered hearing “Salty Dog” from the days of their youth in New Orleans, a song that got dirtier as the night wore on. What, after all, was a “salty dog”? Jelly Roll Morton remembered Bill Johnson, leader of the Original Creole Orchestra, playing it in the early days in a New Orleans’ three-piece band, so Bill Johnson may have been Keppard’s connection to the song.

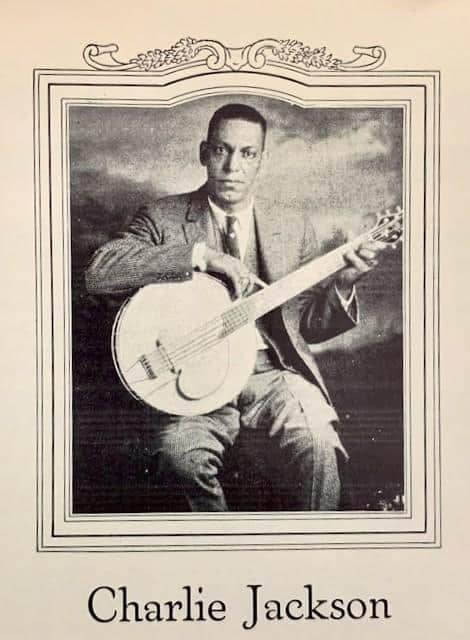

“Papa” Charlie Jackson in a Paramount Records advertising photo, circa 1925.

“Papa” Charlie Jackson, in fact, had two years earlier recorded his own version of “Salty Dog Blues” for Paramount, and it was a bestseller. Although he claimed writing credits, his real role here was to turn explicit lyrics into slightly risqué ones, and let us know that “Papa Charlie done sung this song!”.

It’s the second side of the 78, however, that we really want to listen to. Although it was written by

“Papa” Charlie Jackson in a Paramount Records advertising photo, circa 1925.

“Papa” Charlie Jackson, in fact, had two years earlier recorded his own version of “Salty Dog Blues” for Paramount, and it was a bestseller. Although he claimed writing credits, his real role here was to turn explicit lyrics into slightly risqué ones, and let us know that “Papa Charlie done sung this song!”.

It’s the second side of the 78, however, that we really want to listen to. Although it was written by Jasper Taylor, the band’s percussionist from Arkansas, Stock Yards Strut could as well have been penned by a New Orleans musician fifteen years earlier. In fact, it bears structural similarities to the old New Orleans standard, “Tiger Rag”.

It’s a tour-de-force for Keppard, reminding today’s listener of what it must have been like to have heard the power and beauty of his cornet in his early days in New Orleans.

Candid snapshot of Freddie Keppard from about 1925. This is the point where alcohol and health problems started to seriously impact his life and career, although not necessarily his music. His last known recording session was in 1927, although he continued to perform live until the end of 1930.

It’s a tour-de-force for Keppard, reminding today’s listener of what it must have been like to have heard the power and beauty of his cornet in his early days in New Orleans.

Candid snapshot of Freddie Keppard from about 1925. This is the point where alcohol and health problems started to seriously impact his life and career, although not necessarily his music. His last known recording session was in 1927, although he continued to perform live until the end of 1930.

This photo shows Lil Hardin Armstrong and her band, “Lil’s Hot Shots” from the late 1920s. Freddie Keppard holds what appears to be a trumpet rather than his usual cornet, and looks none too healthy.

What old-timers remembered about Keppard’s horn style in New Orleans was its precision. Each note was played clear, loud, and directly on the beat: Ta Ta Ta Ta Ta ….

This photo shows Lil Hardin Armstrong and her band, “Lil’s Hot Shots” from the late 1920s. Freddie Keppard holds what appears to be a trumpet rather than his usual cornet, and looks none too healthy.

What old-timers remembered about Keppard’s horn style in New Orleans was its precision. Each note was played clear, loud, and directly on the beat: Ta Ta Ta Ta Ta …. You hear that on Stock Yards Strut. That’s the influence of ragtime. King Oliver and Louis Armstrong, developing their cornet styles later, were more influenced by the Blues, with its slur notes coming in slightly behind the beat. Keppard’s is an earlier style.

You hear that on Stock Yards Strut. That’s the influence of ragtime. King Oliver and Louis Armstrong, developing their cornet styles later, were more influenced by the Blues, with its slur notes coming in slightly behind the beat. Keppard’s is an earlier style.

Although Milneburg is years in his past, here Keppard has the freedom to play for himself and recall his youth, plus remember those days when he was indeed “King” Keppard in New Orleans. This is the Keppard music that the old-timers would have remembered approvingly. Unfortunately, this 78 was a poor seller, meaning few people heard it. 78 Quarterly estimates there are only ten copies of the original in the hands of collectors.

By 1926, when Stock Yards Strut and Salty Dog were recorded, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band had already waxed the seminal Gennett sides that would come to define the sound of early New Orleans jazz; and Louis Armstrong was now in the process of redefining the sound of jazz altogether with his Hot Five 78s.

The great Freddie Keppard was relegated to being a historical footnote.

Walk it Sweet Mamma That’s All

No one bothered to interview Freddie Keppard during his lifetime. Whether he would have given an interviewer the time of day is another issue. After all, what did talking about music have to do with playing music?

With Keppard we are left with a few facts, a few more recollections by old-timers, maybe a dozen sepia-tinged photos, a handful of aged 78 records that were recorded way too late, and a lot of myths.

We are also left with a fading 15 cent ticket for a Fourth of July picnic in Milneburg.

Freddie Keppard’s working days as a Chicago musician ended in 1931. No longer physically able to play his cornet, he died in Chicago on July 15, 1933, of alcoholism (cirrhosis), tuberculosis, obesity, and probably diabetes. He was 43 years old.

Post Script: Louis Armstrong was a kid in New Orleans when Freddie Keppard was at the top of his game. Their relationship in later years was often fraught with tension. By 1931, Armstrong was at the pinnacle of the musical world and Keppard was at the lowest rung. Armstrong’s band was leaving Chicago for a tour when Louis told the driver to stop at an old apartment building. He and his band spilled out of the cars, entered the brownstone, and climbed the flight of stairs to pay their respects—and say their goodbyes—to a man who had influenced all of jazz, Freddie Keppard.

Note: the Keppard picnic ticket, the Harmon’s Dreamland advertisement, the “Papa” Charlie Jackson photo, Cook and His Dreamland Orchestra poster (reproduction), and all 78 record labels are from Bowman collection. Most of the other photos have been reproduced many times and come from various sources. Three are rarely seen and are worth noting: the photo of a 10-year old Freddie Keppard was taken from the book Jazz Puzzles, No. 1, by Dan Vernhettes and Bo Lindstrōm, as well as the Keppard photo taken about the time of the Paramount recordings. The photo that Keppard sent to his brother was taken from Bill Russell’s New Orleans Style. All come from the Hogan Jazz Archive Collection at Tulane University and had originally belonged to Louis Keppard.