JELLY ROLL MORTON’S

NEW ORLEANS MEMORIES

Few jazzmen have risen so high, only to fall so low as Jelly Roll Morton.

In the 1920s in Chicago, Morton had been a successful jazz composer, recording artist, and bandleader, introducing New Orleans jazz to the world. But by the 1930s in New York and Washington D.C., his fortunes had fallen. Now, he survived on small jobs, here and there, and visits to the pawn shops. And he schemed to return to the top.

Sadly, Jelly Roll Morton would never return to the top of the music world, if the “top” is measured in dollars and record sales. Instead, in the late 1930s he would do something more important: securing his status as one of the founders and early giants of jazz. And, in the process, he told the story of how New Orleans gave birth to jazz.

Before he died in 1941, Morton would have the opportunity to record again. He would have recording sessions leading full jazz bands composed of some of his favorite New Orleans musicians. But those 78s sold only in modest numbers.

More importantly, Morton had two recording opportunities to sit down at a microphone and piano to tell his story through words and music: memories of coming of age and witnessing the beginnings of jazz on the streets of New Orleans and in the Crescent City’s Storyville District where, as a teenager, he had played piano in the best bordellos. He was a living witness to this bygone era of the early 1900s. Who better than Morton, a natural-born storyteller, to recollect such history?

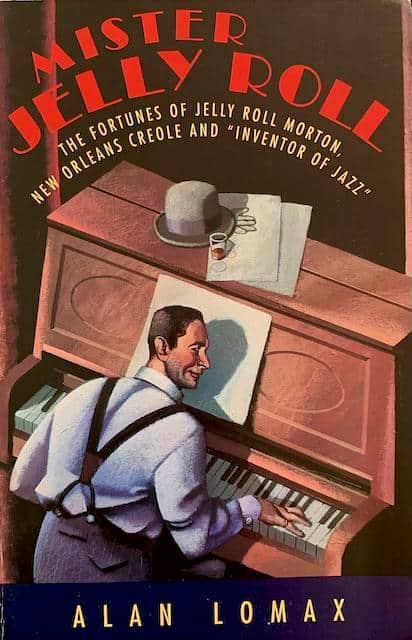

In 1938, in Washington D.C., Alan Lomax, on behalf of the Library of Congress, brought Morton into the Coolidge Auditorium with its concert grand piano and his transcription disc machine. Over a number of sessions, Morton recorded for almost nine hours.

These sessions would provide Lomax with the core material for his important 1950 book on Morton, “Mister Jelly Roll”. For Morton, they would provide a dress rehearsal for his commercial recordings made the following year for General Records: “New Orleans Memories, Jelly Roll Morton”.

Alan Lomax at Library of Congress in late 1930s.

Lomax was a helpful guide in his interviews of Morton, giving him free rein to recall the New Orleans of his youth, to tell his wonderful stories, and to punctuate them with piano and song. Only when venturing into the more salacious material, gleaned from working the whorehouses, did Morton hesitate. But the bottle of whiskey on the piano provided the needed encouragement.

Jelly Roll Morton told an amazing story. But it was one that few would hear during his lifetime because of a desire by the Library of Congress to protect sensitive ears.

Eventually, parts of the recordings were issued on LPs, but it would not be until 2006 that Rounder Records issued the complete unexpurgated 1938 recordings on CD.

The three General Records solo sessions in December, 1939, would be different. With the Library of Congress recordings Morton had been able to tell his story, but with direction and guidance. Now he would tell the story by himself, his way. He would compress that same story into the grooves of five 78s—a half hour’s worth of music. But that was all the time that Morton needed. He would part the mists and transport the listener back to those early days in New Orleans.

Jelly Roll Morton in 1939.

Morton needed to tell this story one last time because he knew that he was dying. He would, in fact, be dead in a year and a half.

Just prior to the Library of Congress recordings, Morton had been stabbed in the chest outside a night club he was working in Washington D.C. The incident was never satisfactorily explained. The wound compounded previously existing heart problems. Although we do not hear his weakness in the record grooves, by the time of the General recording sessions Morton was a very sick man, at times gasping for breath.

On Thursday, December 14, 1939, Jelly Roll Morton went into the Reeves Recording Studios in New York to record eight sides, of which three were rejected. Two days later, he recorded five more sides, with one rejected. Two days after that he recorded one more side. General Records now had ten sides to release in a 78 rpm album, a new format becoming increasingly popular in the late 1930s.

The bulk of these recordings focused on piano players and jazzmen whose music influenced Morton during his youth in New Orleans. From the 78 rpm grooves we hear the variety of sounds that eventually would be woven into a new music called jazz.

Jelly Roll Morton becomes our music teacher. All for the cost of a mere $5.50. Interestingly, that price would equate to about $100 today.

Morton was generally not lavish in praise of fellow musicians. Hence, it was high praise indeed for those he referenced during these recording sessions, of course interpreting their music through his own ears, voice, and fingers.

In the Storyville brothels, Scott Joplin’s ragtime piano pieces had always been popular, and Joplin’s “Original Rags” would remain one of Morton’s favorites. But he doesn’t play it like Joplin. Rather, he takes the original and transforms it into his own creation.

On a jaunt to Florida during his teens, Morton befriended a superb pianist, Porter King, and later composed “King Porter Stomp” in his honor.

In 1939, the modern listener would have known “King Porter Stomp” as a great Swing hit by the Benny Goodman band from a few years earlier.

In “The Naked Dance” Morton played homage to the great Tony Jackson. Jackson, like Morton, played piano in the Storyville brothels, where on special occasions a “naked dance” would be performed for the clientele. From Jackson, the younger Morton would learn “style”—be it piano playing, singing, or clothing. For Morton, Jackson would always be the best.

“Michigan Water” was another favorite of Tony Jackson. Clarence Williams, a fellow Storyville pianist, published it and took composer credit. But, in truth, this was one of the earliest blues, in circulation long before Williams got ahold of it.

Some pianists influenced Jelly Roll Morton’s playing technique. But the piano player who perhaps penetrated most deeply into Morton’s soul, was an attractive young woman ten years his senior, Mamie Desdunes. She was a friend of Morton’s godmother and was one of the few women who played piano in the Storyville brothels. And like Morton, she was a light-skinned Black Creole.

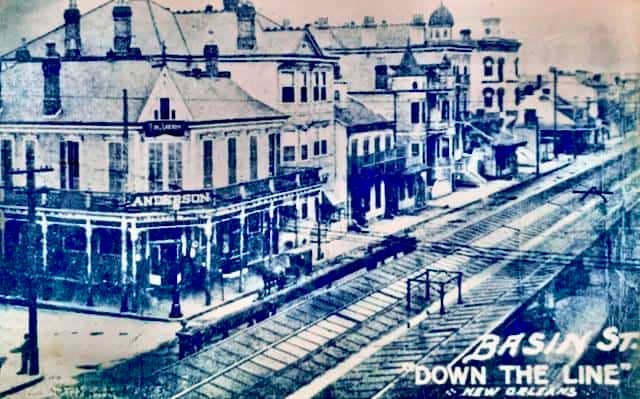

The Storyville mansions in about 1910. This is the row of Storyville bordellos that advertised the most exclusive services, always with a piano playing in the background. Both Mamie Desdunes and Jelly Roll Morton played at these opulent houses along Basin Street.

Desdunes performed with a limitation. She had lost two middle fingers on her right hand in a train accident. But that didn’t affect her playing the blues. As Morton explained: “This is the first blues I no doubt heard in my life. Mamie Desdunes, this was her favorite blues. She hardly could play anything else more, but she really could play this number.”

The common name of the song was “2:19 Blues”. But Morton chose to call it “Mamie’s Blues”. Whether or not Mamie truly wrote the song, we don’t know. But Morton was sure that she had. Knowing that Mamie was long dead, he could have easily taken composer’s credit for the song in 1939. Instead, he made sure that the credit went to Desdunes.

Mamie Desdunes died in New Orleans in 1911, at 32 years of age of tuberculosis—and of perhaps a life lived too fast. Jelly Roll Morton never forgot her. Anyone hearing his plaintive tribute will not forget her either.

Blues singer Jimmy Rushing from Count Basie’s band had this take on the song: “If you took everything Jelly Roll ever did, rolled it together, squeezed it, you’d come up with ‘Mamie’s Blues’…. [T]hat man is singing from his heart, and there ain’t nobody could have done it better.”

To make it real, Morton played piano without using two middle fingers on his right hand.

Another blues recorded by Morton was “Don’t You Leave Me Here”. When Morton claimed composer credit for a song, as he did here, he wasn’t implying that he had literally written the song from scratch, but rather he had taken older folk verses and melodies, rearranged and polished them until ready for copyright and publication. That’s what he did here, a common practice in his era.

Another musician who Morton resurrected from the dead was the legendary cornet player Buddy Bolden who led the first New Orleans jazz band, the sounds of which Morton never forgot hearing as a teenager. “Buddy Bolden’s Blues” had been Bolden’s theme song and a definite crowd pleaser. Morton “cleaned up” the lyrics for the recording session.

Morton would write and record “Mister Joe”, dedicated to his friend Joe “King” Oliver, one of Buddy Bolden’s successors. Two great New Orleans cornet players—Bolden and Oliver. It was King Oliver in Chicago who introduced New Orleans jazz to the world in 1923 with his 78 rpm recordings for Gennett Records.

In “The Crave”, Morton demonstrated his belief that what made great jazz was the judicious inclusion of the sounds of Cuba and the Caribbean which he called the “Spanish tinge”. He had heard and played the components of it all of his life in New Orleans.

Morton wrote the final version of “The Crave”, an upbeat, yet moody, sensuous piece in California in the 1910s. Interestingly, on his Library of Congress version of “Mamie’s Blues”, he also played it with that Cuban—or habanera—beat.

The “Winin’ Boy Blues” was Jelly Roll Morton’s theme song in New Orleans. Morton was indeed the Winin’ Boy.

Despite its prominent role in Morton’s career, his time in New Orleans as a professional pianist playing in the brothels, clubs, saloons, and other music venues, was brief. During the same period of playing piano in Storyville, he was also frequently on the road performing with touring groups and playing piano in red light districts from New Orleans to Florida.

In 1910, at perhaps twenty years old, he would leave New Orleans one last time. After that, he would return only in his memories.

Despite his limited time performing in the Crescent City he was later remembered by old-timers, who in recalling Morton would invariably recall his song, the “Winin’ Boy Blues”. Except the song that they remembered was called the “Windin’ Boy”, as in “winding boy”. And it wasn’t about wine, but about sex. It was Jelly Roll Morton boasting of his sexual prowess, “winding” being a euphemism for sexual intercourse.

Ten songs. Each a history lesson. Each a small gem. Jelly Roll Morton had recorded his memories of New Orleans for the last time.

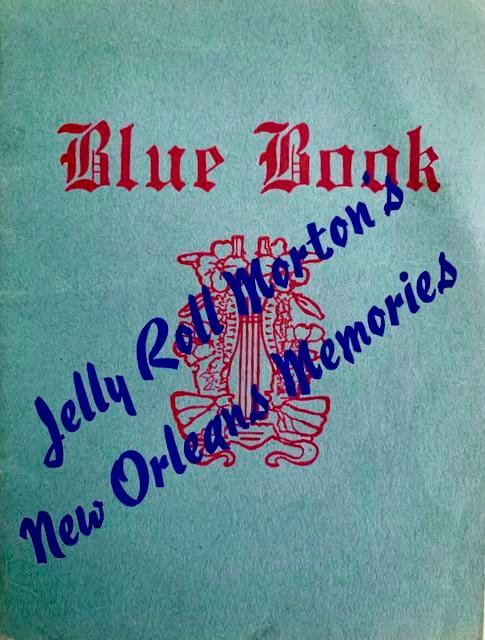

Charles Edward Smith, a young White jazz writer, worked with Morton in producing the General recording sessions. With Morton’s help, Smith wrote a booklet to accompany the album. The booklet provided Morton’s memories of the old New Orleans, as well as giving a commentary for each song.

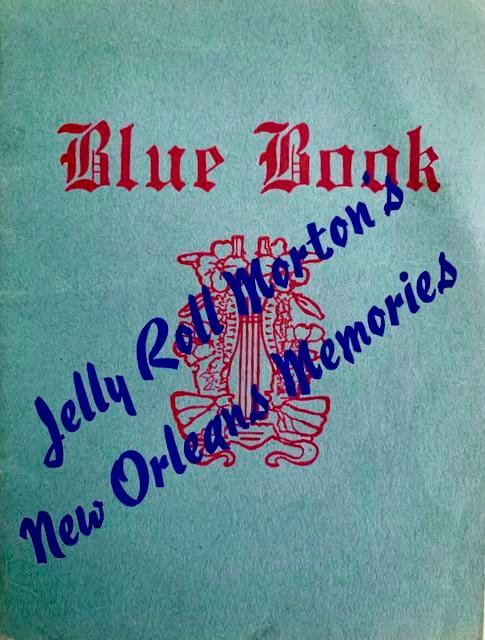

This booklet has proved invaluable to music historians, because they now have Morton giving his own history and interpretation of his songs. As an inside joke, the booklet was printed with the album title superimposed over a facsimile of one of Storyville’s notorious “Blue Books”—guides to finding the best brothels in The District, including previews of the delights they had to offer.

Morton had great hopes that sales of “New Orleans Memories” would enhance his precarious finances. Sales of the album were good. Unfortunately, being a small label, General’s own financial status was shaky. Morton received little compensation for his efforts.

In 1946, General Records shut its doors. But, that didn’t end “New Orleans Memories”. By now it had become a classic album, praised by jazz critics who recognized its historical uniqueness.

When General Records shut down, it sold its assets to Commodore Records. The most important assets Commodore acquired in the deal were the masters to “New Orleans Memories”. The company would quickly release a 78 rpm album of “New Orleans Memories” on its own label.

Soon after, the new vinyl 33 1/3 rpm microgroove records began arriving on the market. Commodore re-issued the album in this new format, too. The album stayed on the market until the advent of CDs in the late 1980s.

Morton had great hopes that sales of “New Orleans Memories” would enhance his precarious finances. Sales of the album were good. Unfortunately, being a small label, General’s own financial status was shaky. Morton received little compensation for his efforts.

In 1946, General Records shut its doors. But, that didn’t end “New Orleans Memories”. By now it had become a classic album, praised by jazz critics who recognized its historical uniqueness.

When General Records shut down, it sold its assets to Commodore Records. The most important assets Commodore acquired in the deal were the masters to “New Orleans Memories”. The company would quickly release a 78 rpm album of “New Orleans Memories” on its own label.

Soon after, the new vinyl 33 1/3 rpm microgroove records began arriving on the market. Commodore re-issued the album in this new format, too. The album stayed on the market until the advent of CDs in the late 1980s.

“New Orleans Memories” was issued on CD by a number of companies. “Last Sessions: The Complete General Recordings” issued by Verve in 2006 is the one to have, comprising not only the original ten issued sides, but also two of the unissued sides: “Sporting House Rag (Perfect Rag)” and “Animule Dance”. Plus, it contains the band sides that Jelly Roll Morton recorded for General Records.

Today, “New Orleans Memories” remains available through a number of streaming services.

Of course, the best way to hear the album is on the original 78 records.

With the exception of the Rodolphe Lucien Desdune’s photo, in Mamie Desdune’s section, all other items and ephemera are from the Bowman collection.