MEMPHIS MINNIE

versus

JOE LOUIS

Thursday, August 22, 1935

Chicago:

In one corner, the undisputed recording champion of the Blues world, weighing in at 120 pounds, “Kid” Douglas—the Queen of the Blues, but best known to her legion of fans as “Memphis Minnie”!

And in the other corner, fresh off his win in Yankee Stadium over Italy’s former heavyweight champion, Primo Carnera, weighing in at 198 pounds is “The Brown Bomber” from Detroit, Joe Louis!

In any contest, the smart money was always bet on Memphis Minnie. She was tough, agile, and resourceful. As fellow bluesman Johnny Shines remembered: “Any men fool with her, she’d go for them right away. She didn’t take no foolishness off them. Guitar, pocket knife, pistol, anything she get her hand on she used.”

Another bluesman who performed with her in Chicago, Homesick James, remembered, “[t]hat woman was tougher than a man. No man was tough enough to mess around with her …. She was a fighter.”

Publicity photo of Memphis Minnie from mid to late 1930s.

Boxing champ Joe Louis may have won all of his thirteen prizefights in 1935, but he never had to go one-on-one against Memphis Minnie. Luckily, he wouldn’t need to, as she was one of his biggest fans.

From 1935 to 1939 a number of Blues singers and musicians would record songs dedicated to the fighting skills of Louis, but Memphis Minnie was one of the first into the recording studio.

On August 22, 1935, she recorded for Vocalion Records her impassioned paean: “He’s In The Ring (Doing That Same Old Thing)”. And like Joe Louis she didn’t pull her punches.

Hey, you people going out tonight,

Let’s go to see Joe Louis fight.

And if you ain’t got no money,

Buddy, go tomorrow night.

‘Cause he’s in the ring now, boys he’s doing that same old thing.

Well, you know Joe Lou carries a mean left.

You know he do!

And he carries a mean right.

And if he hits you with either one,

Sends a charge from a dynamite.

He’s in the ring, boys, doing the same old thing.

I’m a-tellin’ all you prizefighters,

Don’t play Joe for no fool.

After he hits you with that left hook,

Same as a kick from a Texas mule.

He’s in the ring, boys, doing the same old thing.

Joe Louis is a two-fist fighter,

And he stands six feet tall.

And the bigger they come,

He says, the harder they fall.

He’s in the ring, oh! Doing the same old thing.

I’d chance my money with ‘im!

Boys I only had ten hundred dollars,

And I laid it up on my shelf.

I bet everybody passed my house,

In one round Joe would knock ‘em out.

He’s in the ring, mmmmmmmmmmmm!

Doing the same old thing.

I wouldn’t even pay my house rent.

I wouldn’t buy me nothing to eat.

Joe Louis says, “Take a chance with me,

I’m gonna put you on your feet.”

In the ring. He’s still fightin’!

Doing the same old thing!

Memphis Minnie wasn’t known for recording topical songs involving real individuals, so her boosterism of Joe Louis was unusual. Out of approximately 200 songs between 1929 and 1953, she only recorded—in addition to this song—one about an aggressive White lawman (“Reachin’ Pete”), and another that commemorated the death of Ma Rainey (“Ma Rainey”).

Otherwise, her songs generally revolved around men and women with their affairs of the heart—and parts lower. They were “tough gal” stories generally pertaining to sex, the need for it, or lack of it; cheating men or man-stealing women; and the tricks of the trade of prostitution—something of which Memphis Minnie could speak with authority.

Memphis Minnie wrote most of the songs that she recorded Although there is no writer credit on the 78 label for “He’s In The Ring (Doing That Same Old Thing)”, there is every reason to believe that she wrote this one too.

It is obvious when listening to both the issued version of “He’s in the Ring (Doing That Same Old Thing)”, as well as the unissued take recorded the same day, that this song is not Memphis Minnie’s standard fare. Here, emotion is literally pouring out of her voice. Joe Louis is her lover, son, and hero. At times her pride in him is so intense that the power of her voice overwhelms the microphone and recording equipment. It’s as if she is belting out a sanctified gospel song, finding redemption in the young fighter’s prowess in the ring.

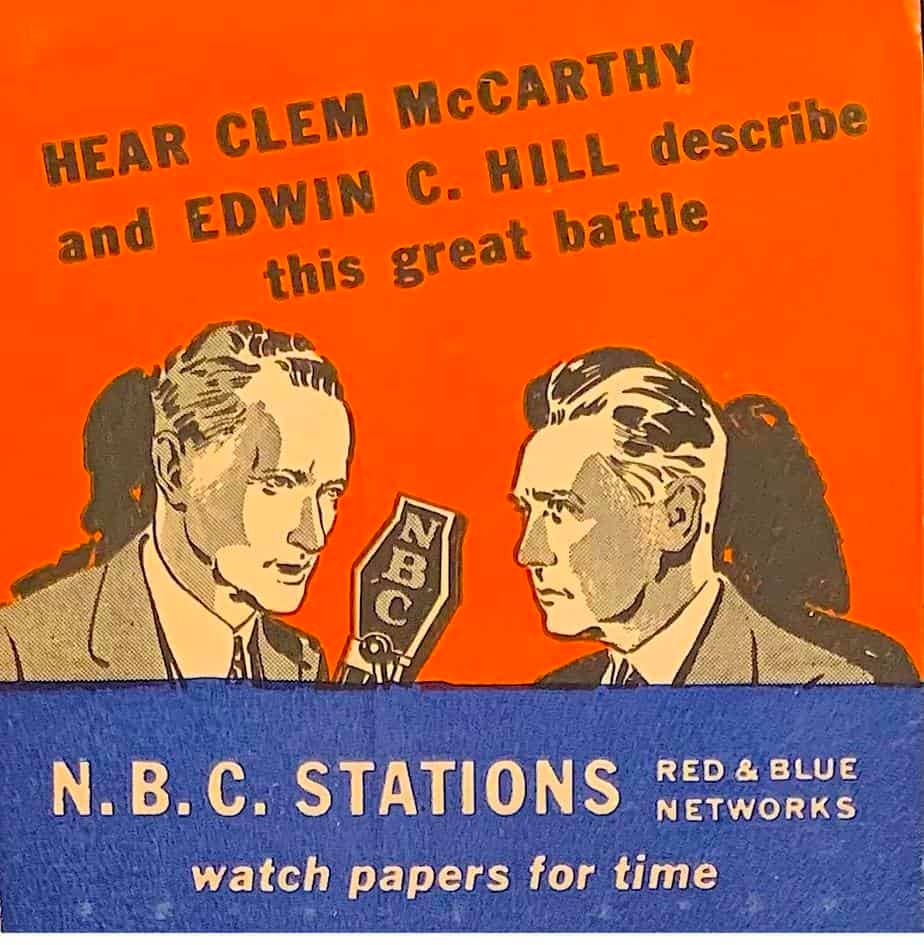

In 1935 Joe Louis was just beginning his ascent. His most famous fights were still to come. He would not become “Heavyweight Champion of the World” for two more years, but he had already earned his status as “The Brown Bomber”.

It is difficult today to fully grasp the importance of the twenty-one year old boxer to the Black community in the 1930s. Black men and women throughout the United States recognized that Joe Louis was in a unique position to break down racial barriers in the country. In time, the unequaled symbolism of Louis would be recognized worldwide.

Perhaps poet Langston Hughes explained it best:

Each time Joe Louis won a fight in those depression years, even before he became champion, thousands of black Americans … would throng out across the land to march and cheer and yell and cry because of Joe’s one-man triumphs. No one else in the United States has ever had such an effect on Negro emotion—or on mine. I marched and cheered and yelled and cried, too.

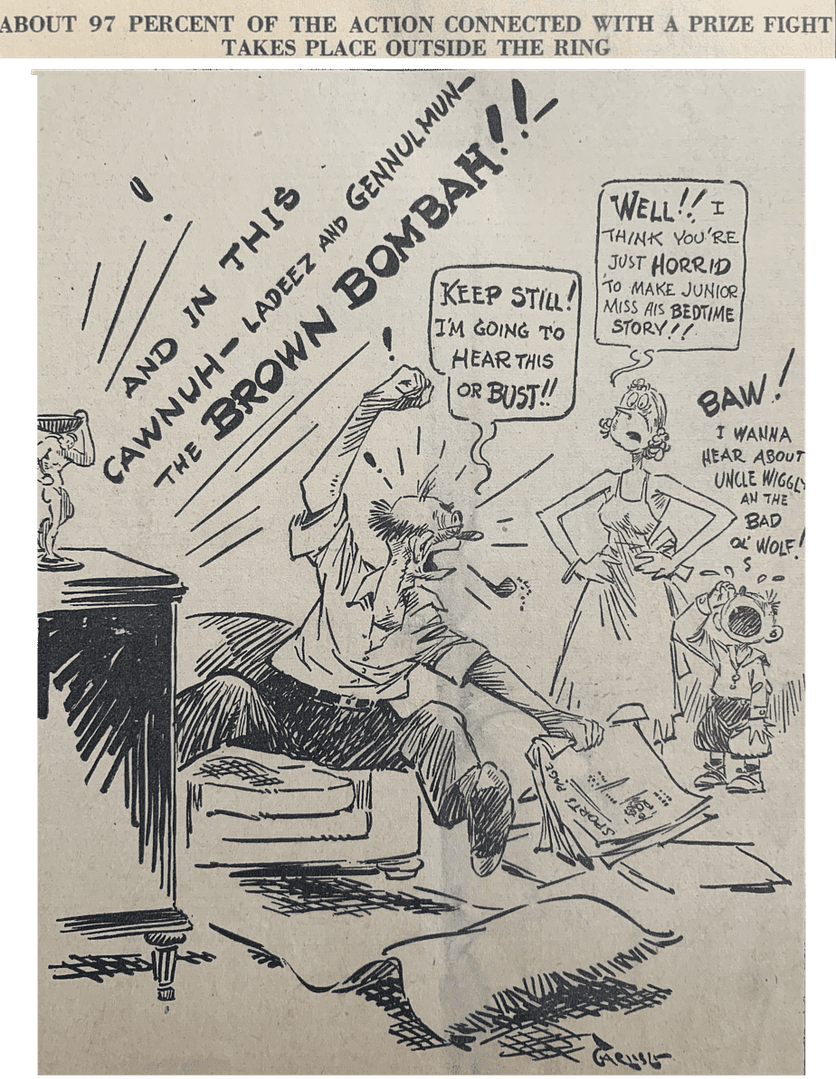

Even Whites were starting to take notice of Joe Louis in 1935, as seen below:

Newspaper cartoon from 1935.

Although Memphis Minnie was seventeen years older than Joe Louis, the two had much in common.

Both were born in the South: she, probably in northern Mississippi (although she claimed Algiers, Louisiana, as her birthplace); and he, in northern Alabama. Both were born into impoverished, sharecropping families. Neither had much education. Both relocated to the North at an early age: Memphis Minnie to Chicago—after spending time on Beale Street in Memphis; and Louis to Detroit. However, both would spend much of their lives on the road. Both rose to the top of their respective professions, and each stayed there much longer than most of their contemporaries.

Memphis Minnie was born Lizzie Douglas, but she changed her name to “Kid” Douglas when she first performed. A record executive later coined the name “Memphis Minnie”. Joe Louis was born Joe Louis Barrow. When “Barrow” was accidentally dropped early in his career, his handlers realized the name “Joe Louis” had a ring to it. So it stuck.

Today, we remember Joe Louis as one of a triumvirate of the greatest heavyweight boxing champions of the twentieth century; Louis, along with fellow Black fighters Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali, promoted the rights of their fellow Black citizens through both their words and actions.

Louis is particularly celebrated for giving Hitler his comeuppance in 1938 when he decisively defeated Nazi Germany’s “great white hope”, Max Schmeling, at Madison Square Gardens, a match of political significance that was followed around the world.

But there was an earlier fight of political significance where Joe Louis walked away the victor, thus further endearing him to Blacks in this country.

In 1935, Italy began a bullying diplomatic campaign against Ethiopia, one that would soon escalate into a horrifying war in which the modern Italian army used machine guns, aircraft bombers, and other new weapons against Black Ethiopian tribesmen. Blacks in the United States took notice. When Joe Louis defeated Italian fighter Primo Carnera in a knockout on June 25, 1935—two months before the Memphis Minnie recording—many Blacks saw it as a defeat of Italy’s strongman and Fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini.

Joe Louis in his early years as a prizefighter.

In 1936, Joe Louis would lose his first fight to Max Schmeling—one of only three losses out of his total 69 professional fights. The following year Louis would win the title of “Heavyweight Champion of the World”, which he would hold until 1949—a record in itself. But being champion wasn’t enough. What Louis, the Black community, and no doubt Memphis Minnie yearned for was a rematch against Germany’s Schmeling. They got it in 1938. In what became known as “The Battle of the Century”, Louis battered Schmeling. The boxing match lasted just over two minutes. Schmeling may have suffered the physical pain, but it was the Nazi’s doctrine of White superiority that took the bigger hit.

As for Joe Louis: he was simply in the ring, doing that same old thing.

After recording “He’s In The Ring (Doing That Same Old Thing)”, Memphis Minnie and her two sidemen, Black Bob on piano and Bill Settles on string bass, would turn their attention to an infectious, upbeat instrumental. The mix is such that if Memphis Minnie was playing guitar, you don’t hear it. Supposedly she was playing spoons, but likewise they are hard to hear. What you do hear from her are lively vocal encouragements to Black Bob and Settles, whose string bass sometimes gets lost in the mix. What we really have is Black Bob’s energetic piano playing. But that’s enough—his playing is a tour de force.

“Joe Louis Strut” would be issued as the flip side of “He’s In The Ring (Doing That Same Old Thing)”.

Just why this instrumental was called “Joe Louis Strut” is a mystery. Because it was recorded at the same time as “He’s In The Ring (Doing That Same Old Thing)”, the title was probably just a marketing ploy by Vocalion to sell more 78s to Joe Louis fans.

And there were millions of them.

Postscript: Joe Louis’ epic win over Max Schmeling in “The Battle of the Century” in 1938 has often been viewed as a battle between the Free World and the Nazis. Hitler’s publicists certainly touted it as such in the days leading up to the match. But not Schmeling. He was a German, but not a Nazi. He refused Nazi honors, and hid two Jewish children from Nazi mobs. Broke at the end of World War II, Schmeling rebuilt his finances working for Coca Cola. He and Joe Louis became friends. Schmeling would financially help the often financially-strapped Louis in his later years.

With exception of the Memphis Minnie photo, all other ephemera is from the Bowman collection.