ORDÉN POSTAL

DE DISCOS

MEXICANOS 78 RPM

Mail Order

Mexican

78 RPM Records

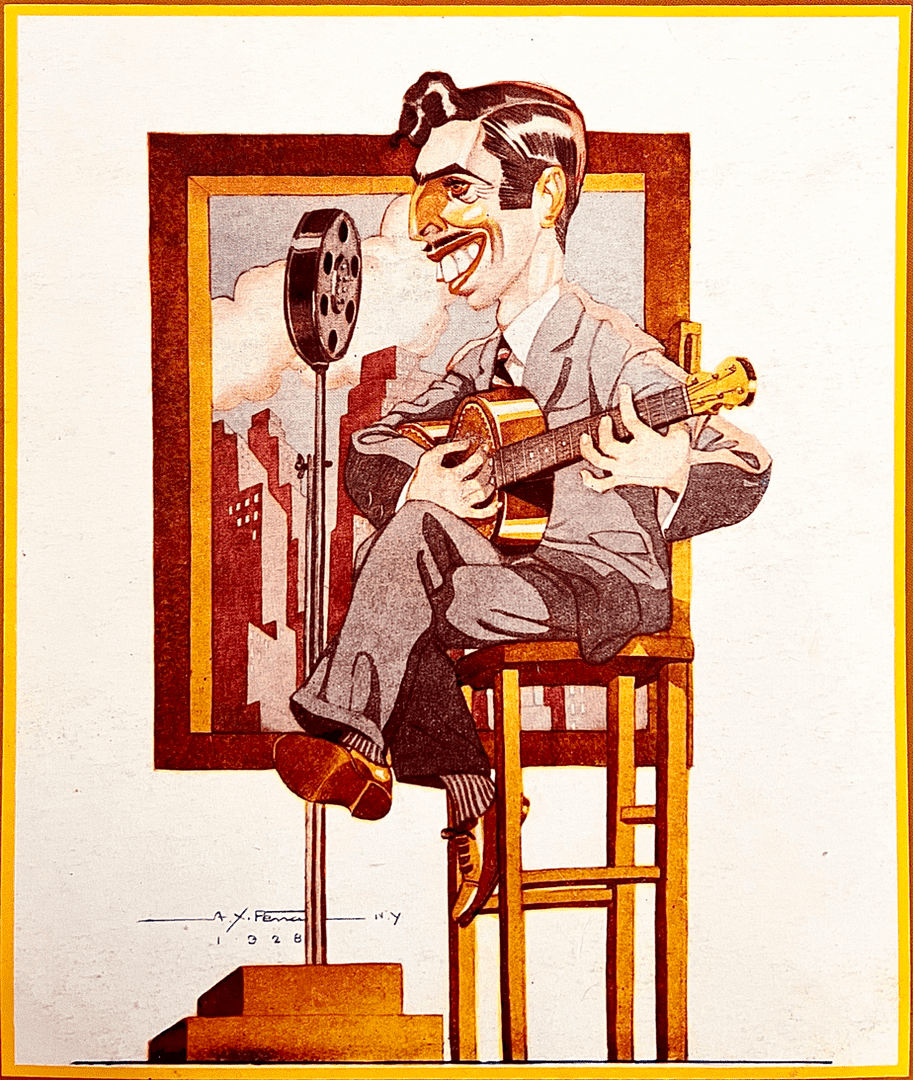

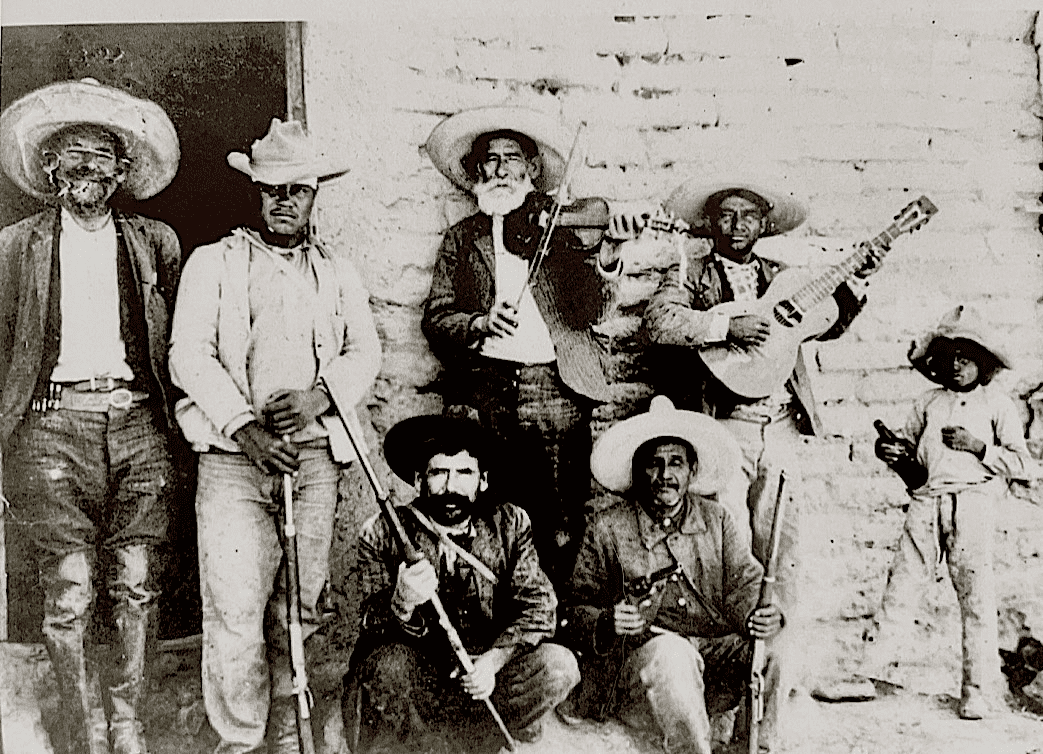

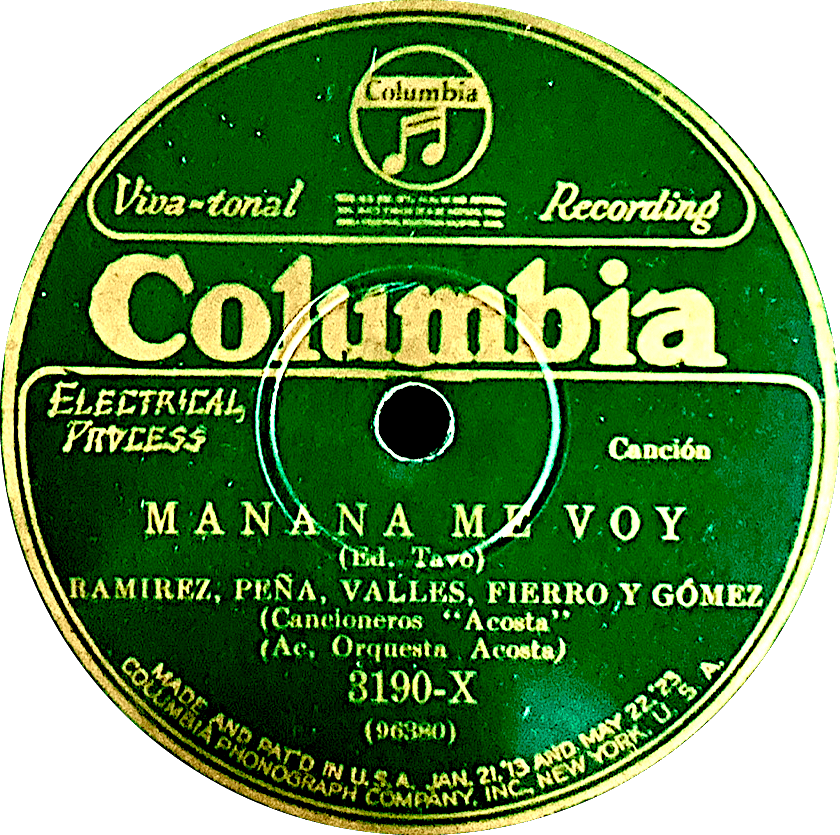

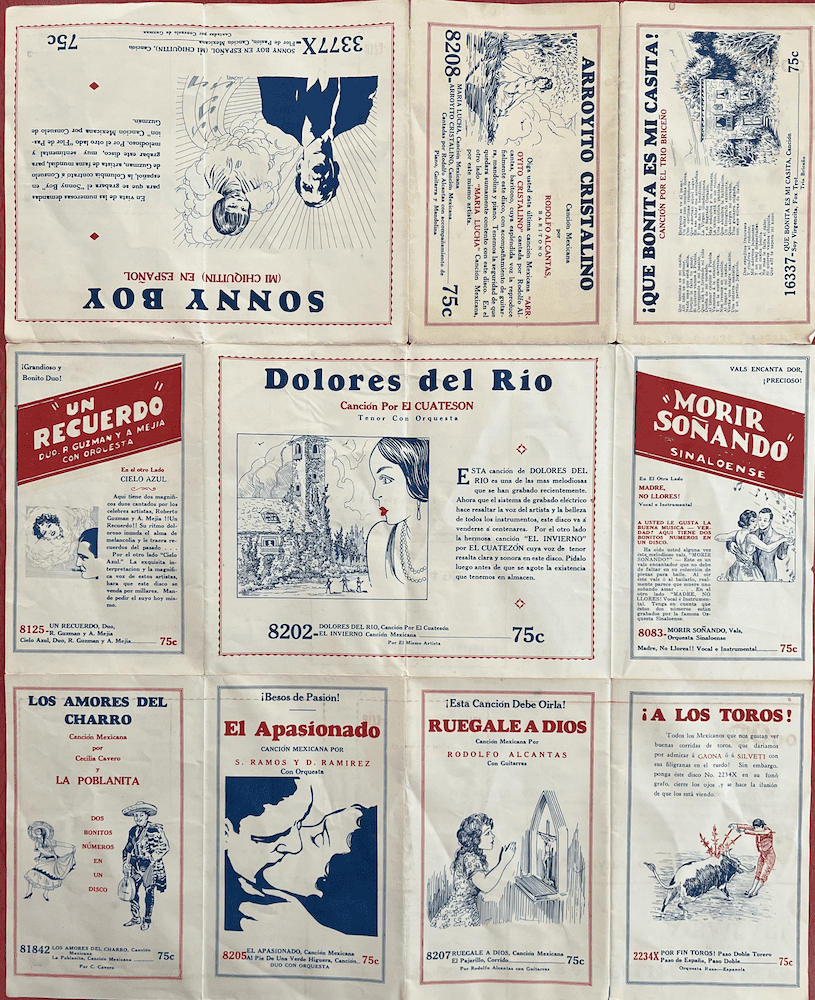

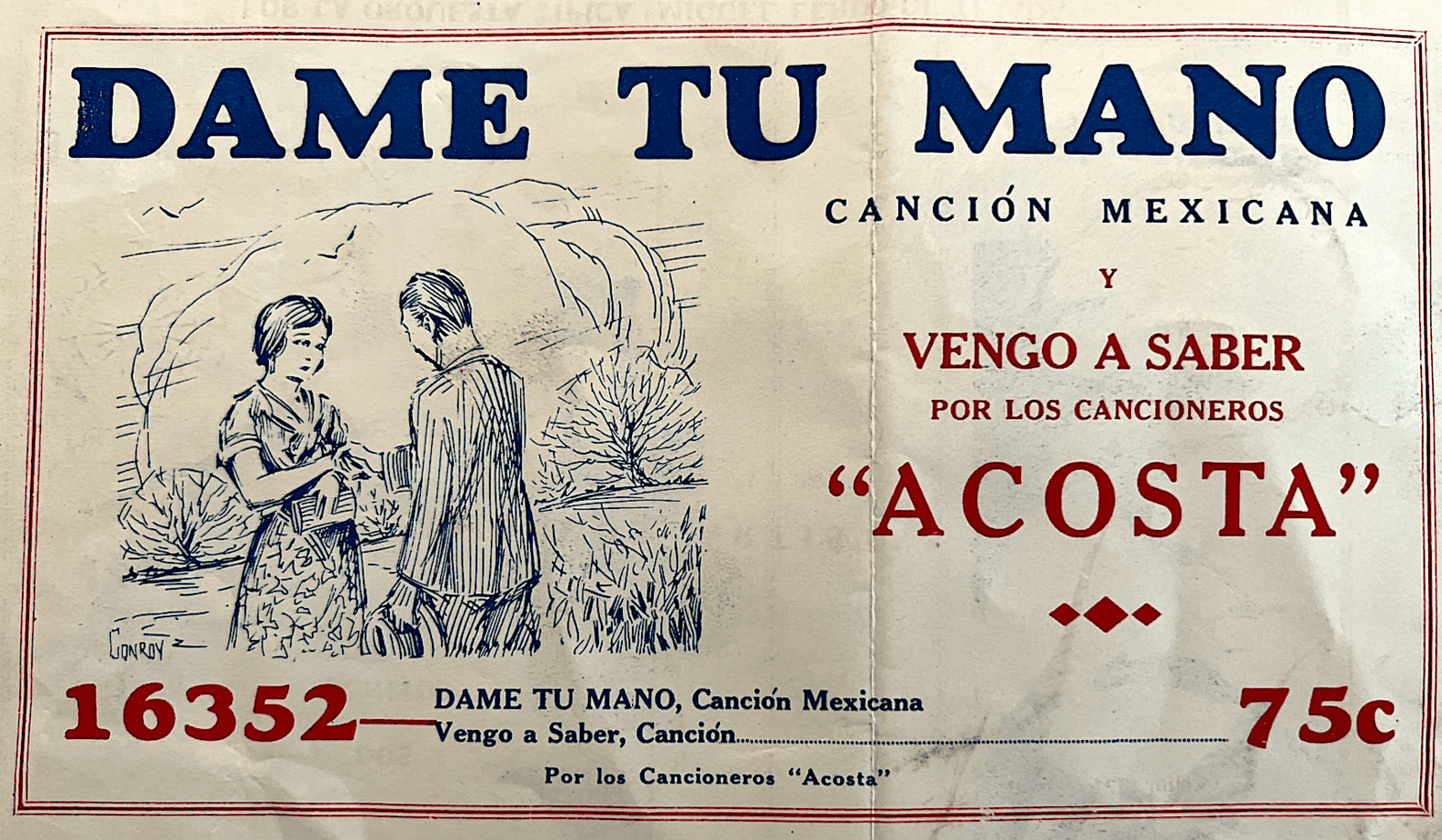

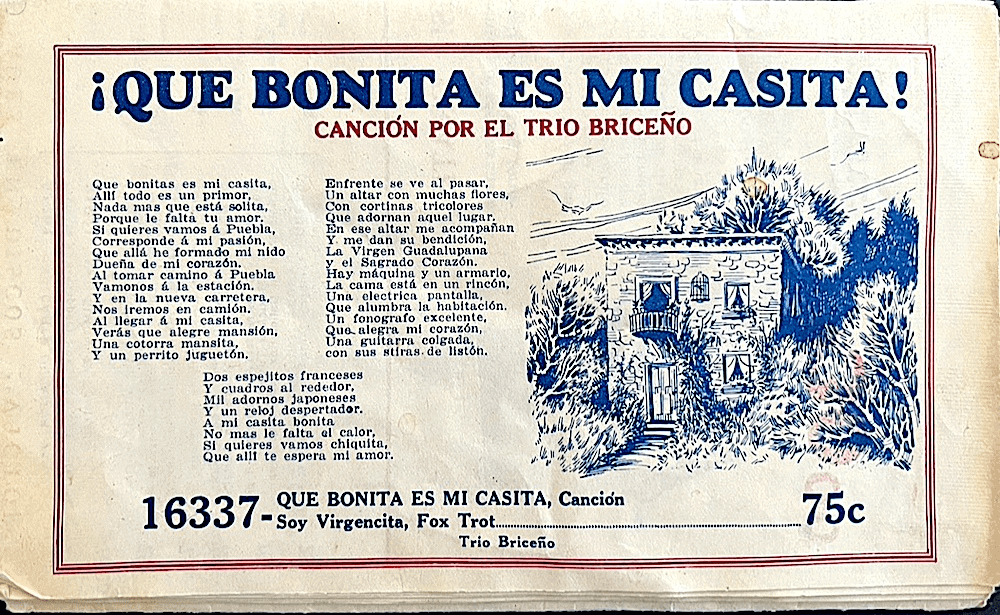

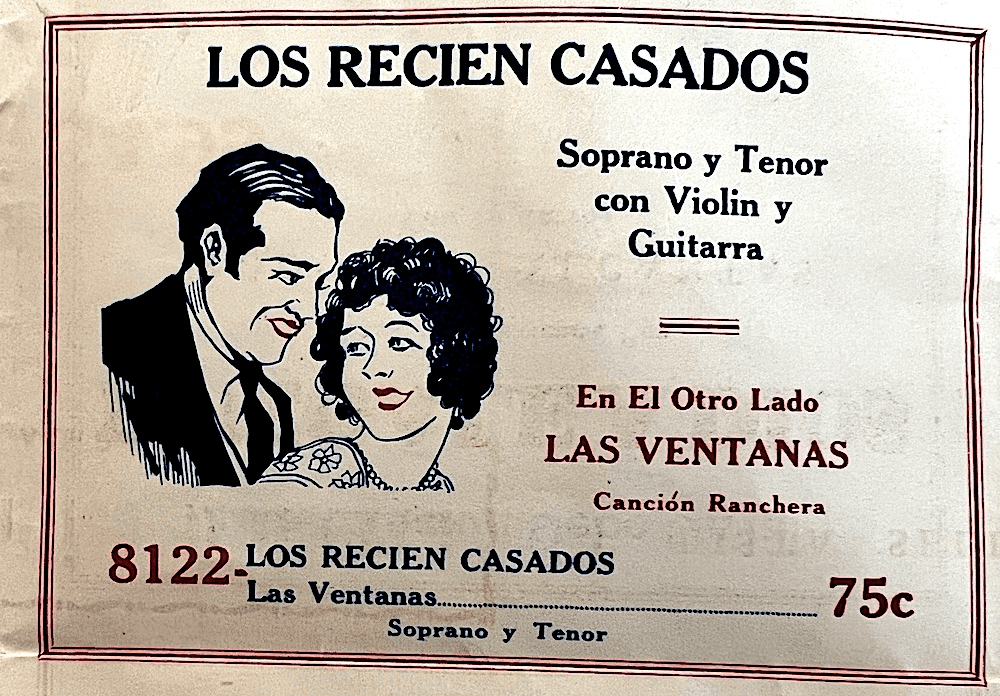

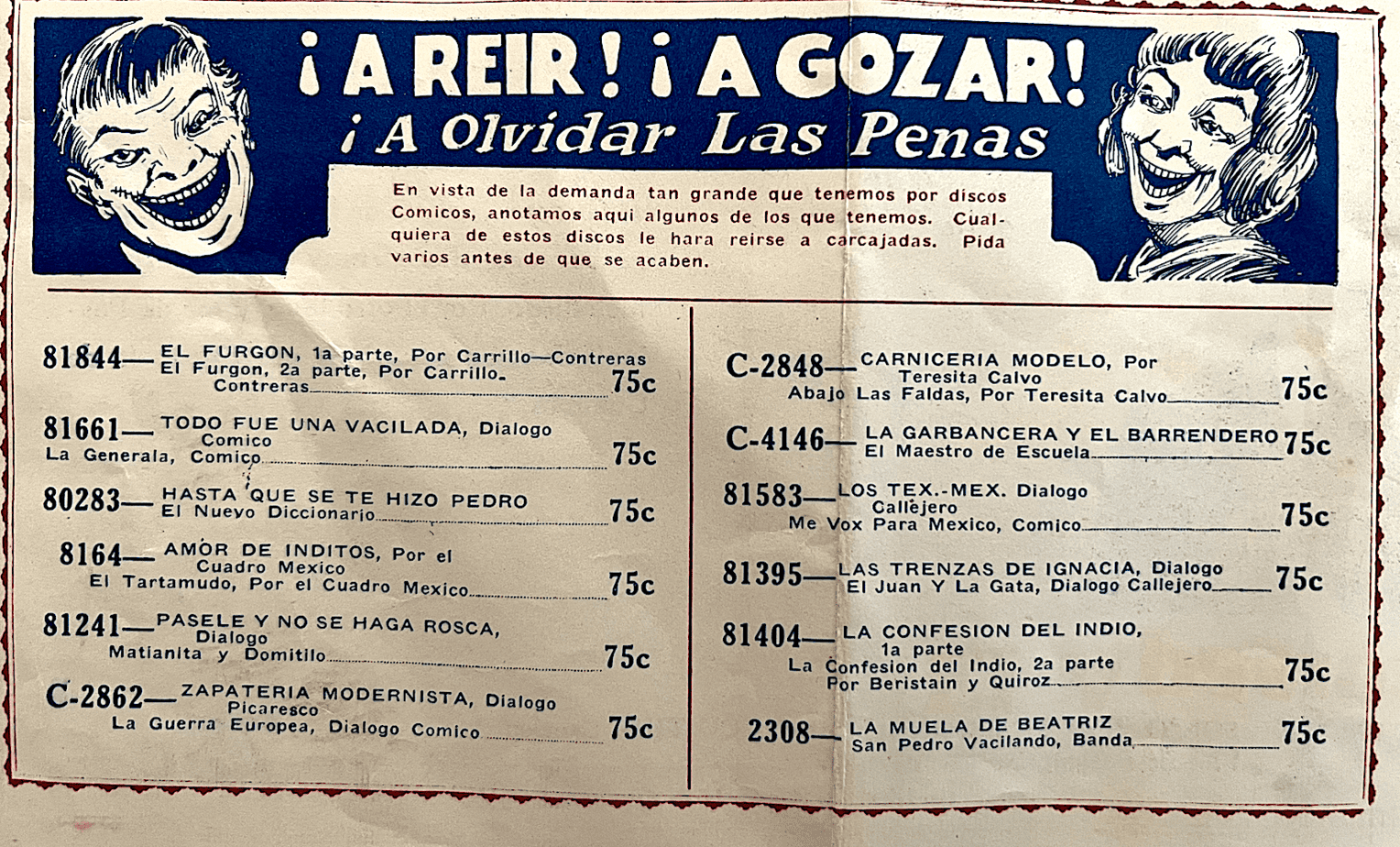

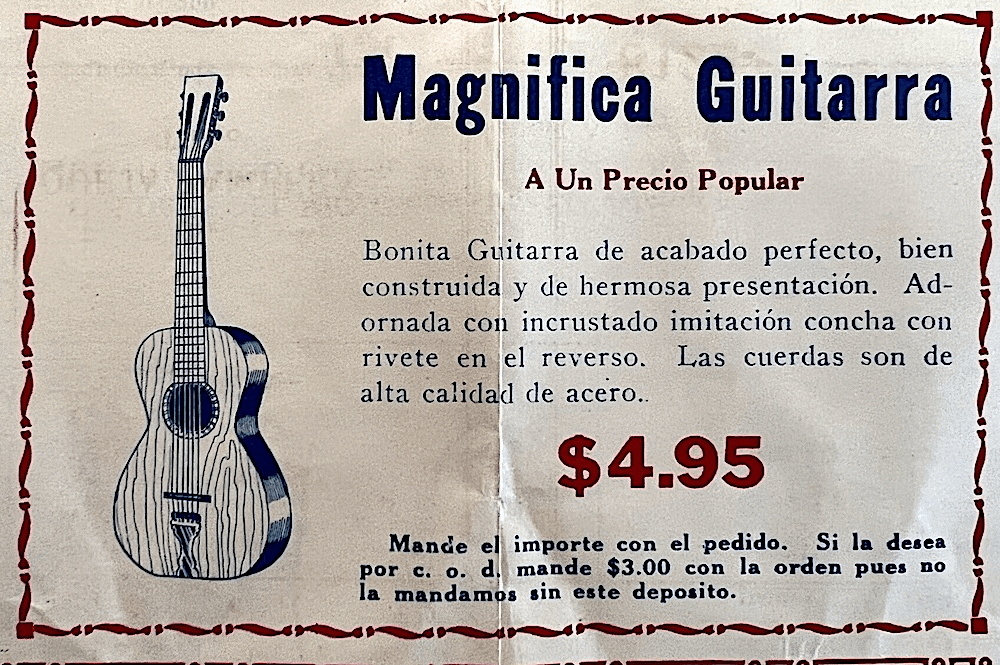

Above is one of many illustrations for an advertising foldout that was distributed about 1928 by the St. Louis Music Co. for the mail-order sale of 78 rpm records by Mexican recording artists. In addition to selling Mexican 78s, the business also sold country and Blues records

In the city of St. Louis today there exists St. Louis Music, a business founded in 1922 for the sale of violins and other musical instruments. This is probably the same business. Because many early music stores sold not only instruments, but also radios, phonographs, and 78s, the mail-order sale of records may have been a sideline business for the store.

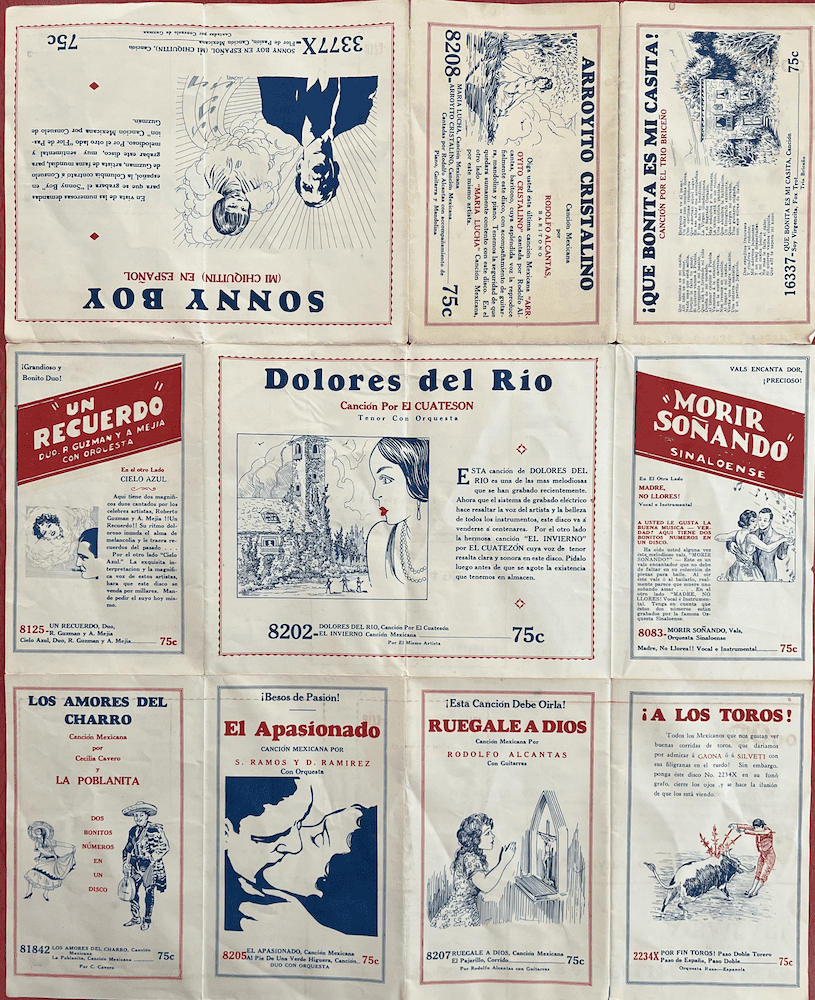

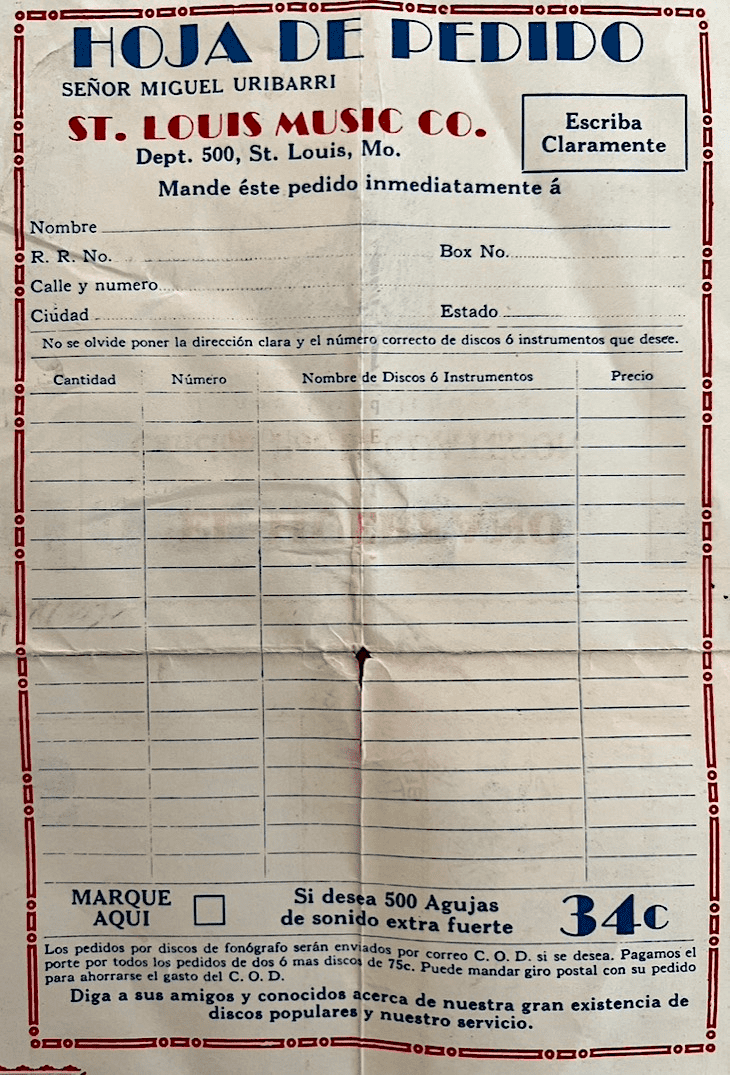

When opened, the Mexican record advertising foldout, printed in red and blue ink on white paper, is approximately 24 x 30 inches. Almost one hundred years old, it is starting to show its age. It was designed to be mailed in an envelope. Selected recordings are highlighted by bold graphics and all told, there are about 130 Mexican records listed that the prospective buyer can choose from.

CLICK ON ABOVE IMAGE TO VIEW THE UNFOLDING OF THE ADVERTISEMENT.

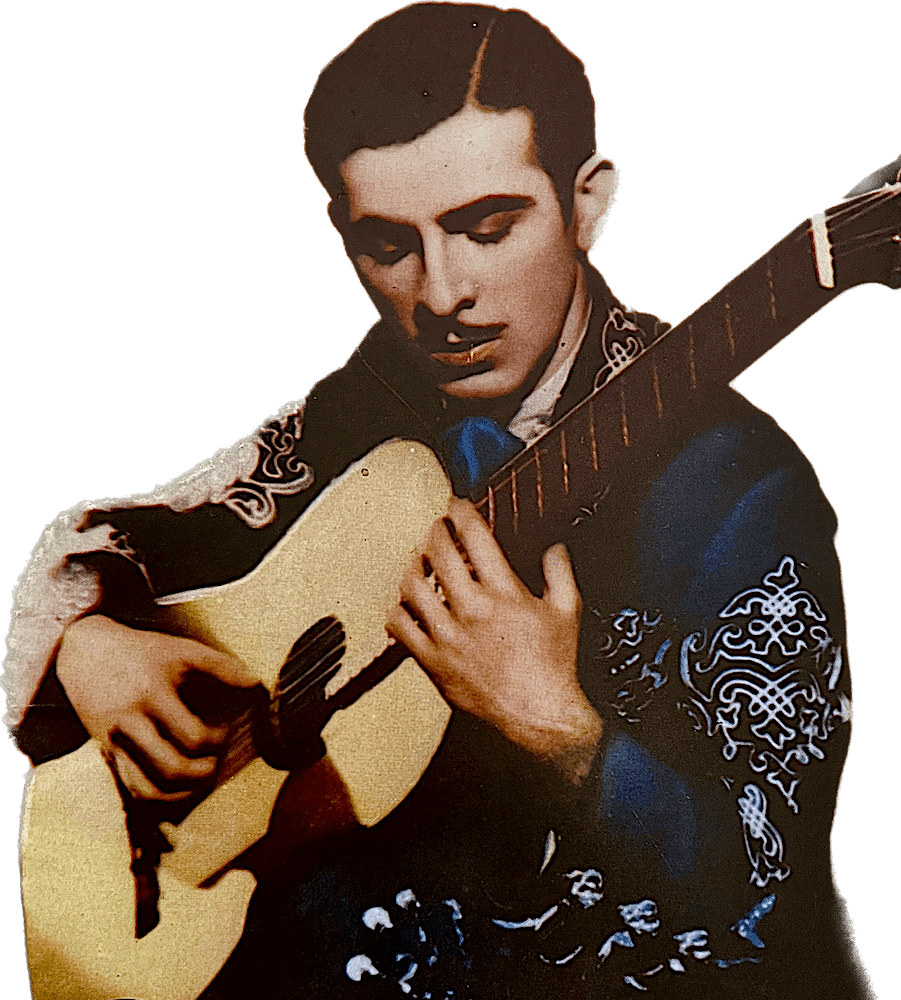

GUTY CARDENAS

This unique item was found in an El Paso antique store twenty-five years ago.

Tiendas de Discos Versus Correo

Record Stores Versus Mail

Much of the story behind this advertisement is unknown, there being limited information available about the making, marketing, and distribution of Mexican records in the United States in the 1920s.

But such sales of 78s by mail-order were not unique in this country, nor limited to any one ethnic group or type of music. Record customers, regardless of the color of their skin, ordered records through the mail with great frequency in the 1920s, and these sales were immensely profitable for the recording companies and the numerous mail-order record distributors located throughout the country.

In particular, mail-order sales served the needs of customers in rural areas and other sections of the country where retail outlets selling 78s were limited or non-existent.

In larger towns and cities records were sold in general stores, book stores, furniture stores, music instrument stores, etc. In such communities the customer had more opportunities to go record shopping, with many stores giving the customer a chance to listen to a record before buying it.

Even in a big city, however, the largest stores could only stock a limited number of 78s, hence, a retailer always had on hand the latest record flyers, pamphlets, and catalogs to hand to their customers. Any record listed could be ordered through the store. Record buyers quickly became familiar with the concept of obtaining 78s through the mail.

Mexican Record Catalog

COLUMBIA RECORDS DOMINATED THE RECORDING OF MEXICAN MUSIC IN THE 1910s, 1920s, AND EARLY 1930s. THE ARTISTS SHOWN IN THIS 1930 CATALOG ARE, FROM TOP TO BOTTOM: SALVADOR y CONSUELO QUIROZ; CONCHITA PIQUER TONADILLERA; AND RUBIO y MARTINEZ.

Ever mindful of the need to cater to their various ethnic markets for record sales, all of the major record companies routinely issued specialty catalogs. For Mexican 78s sometimes a catalog would be devoted exclusively to those discs, although often a company would put out a catalog for “Spanish” music that would include records by artists from Spain, the Caribbean, South America, Central America, and Mexico. To order records from a company catalog, you had to place your order through a store selling records.

Only in the largest cities or large centers of Mexican and Mexican-American populations, were there record stores that specialized in Mexican music. In Los Angeles, for example, La Casa de Musica (Repertorio Musical Mexicano) was founded in 1915 by Mexican immigrant Mauricio Calderón. As Calderón exhorted in a 1918 newspaper advertisement:

Mexicans: This store was established exclusively for your patronage. No other place could serve you better because we, in a word, treat you like Mexicans and compatriots.

In addition to 78s, La Casa de Musica sold phonographs and musical instruments, and became a hub for Mexican musical entertainment in southern California. By the 1930s it was serving as a go-between for local Mexican American artists and the recording companies. It remained in business until the mid-1940s.

Many such Mexican music stores offered mail-order services for purchasing Mexican records.

Explains Chris Strachwitz, founder of Arhoolie Records:

There were many retailers of Mexican 78s in the 1920s (and beyond!). You can find their ads in the Spanish language newspapers of that era—in La Prensa [San Antonio] and La Opinión [Los Angeles], for example. Of course in those days they all did mail-order.

Música y Copradores

Music & Buyers

In rural areas and in many parts of the United States where record stores selling Mexican 78s were non-existent, Mexicans and Mexican-Americans had limited shopping opportunities for the music they desired. Mail-order services, such as those of the St. Louis Music Co., therefore, played a critical role in connecting Mexican and Mexican-American customers with Mexican records.

So, how did someone wishing to buy Mexican records find a mail-order distributor? The most common advertising venue for these companies was the Spanish-language newspapers published in the United States, especially in the border states and in large cities such as New York City and Los Angeles.

It’s worth noting that not only the mail-order distributors, but also the major record companies themselves advertised their latest Mexican records in both English and Spanish-language newspapers.

Simply mail your request for a catalog, and you will quickly receive a listing of available 78s. Fill out your order form, drop it in an envelope with payment, and soon your Mexican records will be delivered by the postman to your doorstep or to your local post office.

As early as 1904, major record companies first began recording Mexican music in Mexico City, finding it a lucrative addition to their recording portfolios.

The dangerous upheavals of the Mexican Revolution, beginning in 1910 and lasting throughout the decade, temporarily soured American businesses recording in Mexico. The record companies brought Mexican musical artists into the United States to record their music. Even with the return of the American recording crews to Mexico in the 1920s, it was now clear that there was a large demand for Mexican records recorded by Mexican artists north of the border.

By the 1920s, Mexican records were recorded by the major American recording companies primarily in either Mexico City or New York City, although occasionally recording sessions took place in other cities such as Chicago or Los Angeles.

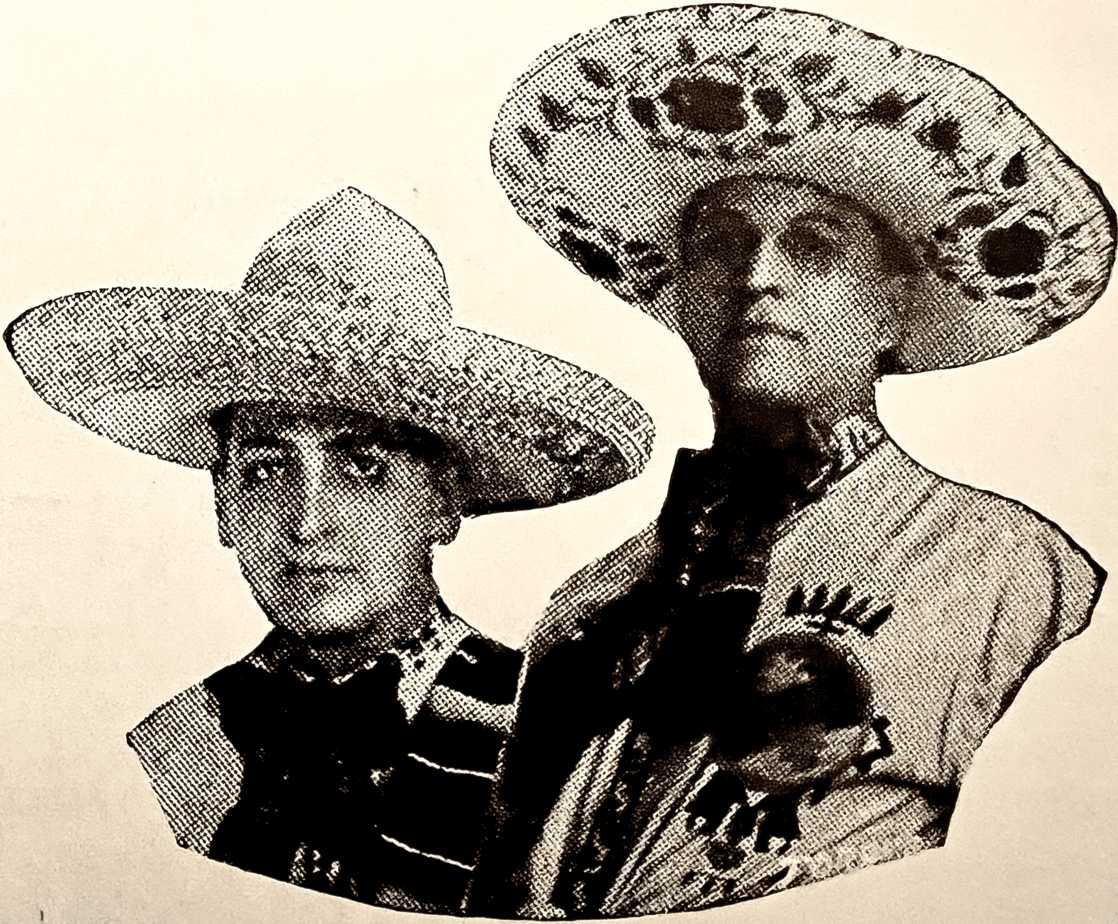

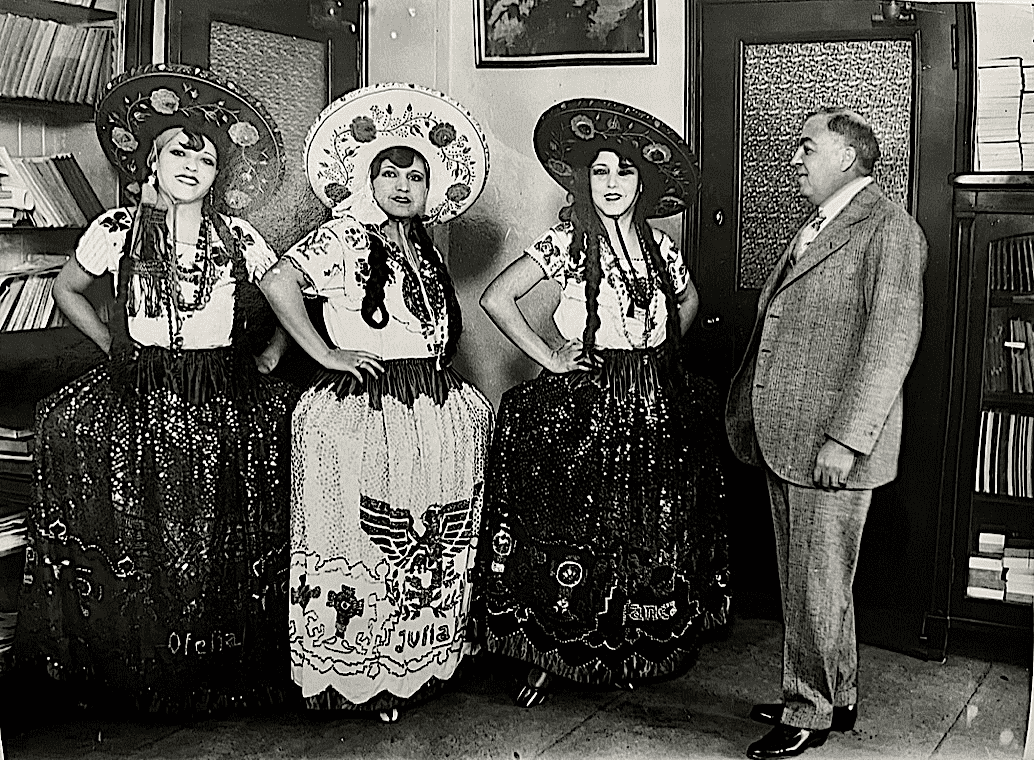

Most of the Mexican singers and musicians who made records resided in Mexico and often traveled to the United States to record. One example was the Trio Garnica Ascencio, a pioneering Mexican vocal group who popularized romantic trios in the 1920s. The group toured Mexico and the United States attired in the traditional “china poblana” dress style as shown below. This 1928 news photo was taken in New York City shortly the singers’ arrival from Mexico. Their schedule included both touring and recording. Their 78s were marketed on both sides of the border.

At the same time that members of the Trio Garnica Ascensio were recording for Victor Records in the United States, their friend Guty Cárdenas was recording nearby for Columbia Records. On occasion he would accompany them on piano.

Cárdenas may have been Columbia’s best selling Mexican artist between 1928 and 1932. Having lived fast and died young, he remains popular today, a cult figure in Mexican music. Coming from the Yucatan region of southern Mexico, Cárdenas, who wrote many of his own songs, possessed incredible vocal and instrumental talents, recording everything from traditional Mexican folk songs to Mexican fox trots. For several years he resided in New York City, cultivating a successful musical career and marrying an American. He eventually returned to Mexico City only to meet a mysterious death, shot in a local bar. He was twenty-six years old.

Record listings for both the Trio Garnica Ascensio and Guty Cárdenas are found in the St. Louis Music. Co. flyer.

The American mail-order companies primarily marketed records to Mexican and Mexican-American customers on the north side of the U.S.-Mexico border. The residents of Mexico had easier access to stores selling Mexican records, and, therefore, were less likely to need a mail-order service.

But there was another reason that the mail-order companies primarily focused on Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in the United States:

The Mexican working class groups north of the Rio Bravo [Grande], unlike their counterparts in Mexico, had direct access to the new technology and a credit system that allowed them to become the earliest consumers of traditional phonographic recordings. A study made during the 1920’s by anthropologist Manuel Gamio shows the widespread existence of phonographs in Mexican communities in the United States: even “in poor huts made of wood and tin, with thatch, canvas, or heterogeneous materials … the phonograph is frequent.” Furthermore, Gamio demonstrated that according to Mexican customs declarations, phonographs and discs were the items most frequently found in the possession of returning immigrant workers.

Guillermo Hernandez, historian

In the 1910s and early 1920s Mexican workers in the United States frequently purchased 78s of traditional “corridos”—or ballads—spawned by the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), perhaps because such workers often came from Mexico’s border states, areas disproportionately affected by the war.

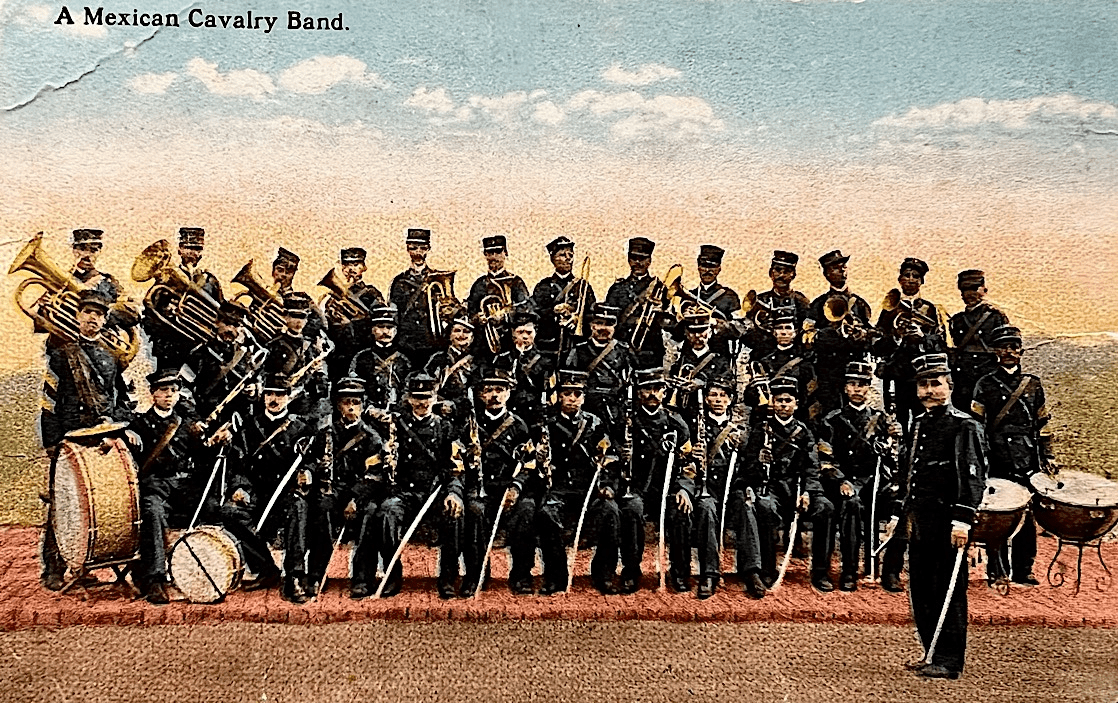

Also in these early days the formal music of military and municipal brass bands was very popular with Mexican immigrants.

Mexican Military Bands

They weren’t just military bands. They could also be municipal bands. And police bands. Originally they were brass bands, but in time would come to include woodwinds and strings. They were extremely popular in Mexico, having been based on European band models, and in time their popularity would extend across the border and throughout the United States, rivaling in popularity American bands such as that John Phillip Sousa.

Beginning in the 1880s, the Mexican government began sending these bands to the United States as a matter of cultural awareness. This became a surprisingly popular goodwill gesture with many such bands traveling north, and once across the border fanning out throughout the United States, playing at music halls, exhibitions, conventions, fairs, and other entertainment venues. The advent of the railroads facilitated traveling, while the advent of recorded music on cylinders and 78s allowed the music to spread throughout the United States, making the music available to those unable to attend live concerts.

In Mexico the sounds of the military bands were familiar to citizens of all economic walks of life. Because most Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the United States in the early decades of the 1900s were immigrants, they too were familiar with this music. What did change in the United States, however, was that White audiences likewise became fans Mexican bands.

The music played by the military bands was a potpourri of sounds ranging from pieces built around Mexican folk tunes, compositions of Mexican composers, and European light classical music. Keeping up with the times, the conductors would come to incorporate more and more sounds of American popular music, yet there remained a formality to the music. These were, after all,

THE ABOVE 12-INCH 78 RPM RECORD WAS RECORDED BY VICTOR IN MEXICO CITY IN 1907, ALTHOUGH THIS IS A LATER REPRESSING. FELIX DIAZ MARCH WAS WRITTEN BY VELINA M. PRESA CASTRO, WHO WAS DIRECTOR OF THE POLICE BAND OF MEXICO CITY. WHY FELIZ DIAZ WAS SO HONORED IS A MYSTERY GIVEN THAT EVEN HIS UNCLE, PRESIDENT PORFIRIO DIAZ, SHOWED LITTLE RESPECT FOR HIM. DURING THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION, TIME AND AGAIN, FELIZ DIAZ INVARIABLY PICKED THE WRONG SIDE IN THE CONFLICT. HE NEVER WON A BATTLE AND SPENT MUCH OF HIS LIFE IN EXILE FROM MEXICO.

They weren’t just military bands. They could also be municipal bands. And police bands. Originally they were brass bands, but in time would come to include woodwinds and strings. They were extremely popular in Mexico, having been based on European band models, and in time their popularity would extend across the border and throughout the United States, rivaling in popularity American bands such as that John Phillip Sousa.

Beginning in the 1880s, the Mexican government began sending these bands to the United States as a matter of cultural awareness. This became a surprisingly popular goodwill gesture with many such bands traveling north, and once across the border fanning out throughout the United States, playing at music halls, exhibitions, conventions, fairs, and other entertainment venues. The advent of the railroads facilitated traveling, while the advent of recorded music on cylinders and 78s allowed the music to spread throughout the United States, making the music available to those unable to attend live concerts.

In Mexico the sounds of the military bands were familiar to citizens of all economic walks of life. Because most Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the United States in the early decades of the 1900s were immigrants, they too were familiar with this music. What did change in the United States, however, was that White audiences also became fans of Mexican bands.

THE ABOVE 12-INCH 78 RPM RECORD WAS RECORDED BY VICTOR IN MEXICO CITY IN 1907, ALTHOUGH THIS IS A LATER REPRESSING. FELIX DIAZ MARCH WAS WRITTEN BY VELINA M. PRESA CASTRO, WHO WAS DIRECTOR OF THE POLICE BAND OF MEXICO CITY. WHY FELIZ DIAZ WAS SO HONORED IS A MYSTERY GIVEN THAT EVEN HIS UNCLE, PRESIDENT PORFIRIO DIAZ, SHOWED LITTLE RESPECT FOR HIM. DURING THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION, TIME AND AGAIN, FELIZ DIAZ INVARIABLY PICKED THE WRONG SIDE IN THE CONFLICT. HE NEVER WON A BATTLE AND SPENT MUCH OF HIS LIFE IN EXILE FROM MEXICO.

The music played by the military bands was a potpourri of sounds ranging from pieces built around Mexican folk tunes, compositions of Mexican composers, and European light classical music. Keeping up with the times, the conductors would come to incorporate more and more sounds of American popular music, yet there remained a formality to the music. These were, after all, bands that wore military uniforms. Perhaps the heyday of these bands was 1905 through 1925. They performed and recorded extensively. But taste in music was changing and the formality of this music lost out to the sounds of singers and bands performing more popular music in the Mexican and Mexican American communities in the United States.

bands that wore military uniforms. Perhaps the heyday of these bands was 1905 through 1925. They performed and recorded extensively. But taste in music was changing and the formality of this music lost out to the sounds of singers and bands performing more popular music in the Mexican and Mexican American communities in the United States.

The 1930 Columbia catalog, above, was still listing recordings by the military bands; however, 78s by these bands were no longer available in the St Louis Music Co. mail order form. Musical trends were changing.

By the 1920s, however, Mexican musical tastes were changing as they were influenced by the new musical sounds coming from the United States.

In Mexico in the 1920s, phonographs and 78s were purchased primarily by the upper class which influenced the type of 78s sold. In the United States, however, Mexicans and Mexican Americans of all social classes bought them and they sought a broad selection of Mexican music, as shown in the St. Louis Music Co. advertising foldout.

What can we learn in reviewing the advertisement from the St. Louis Music Co.?

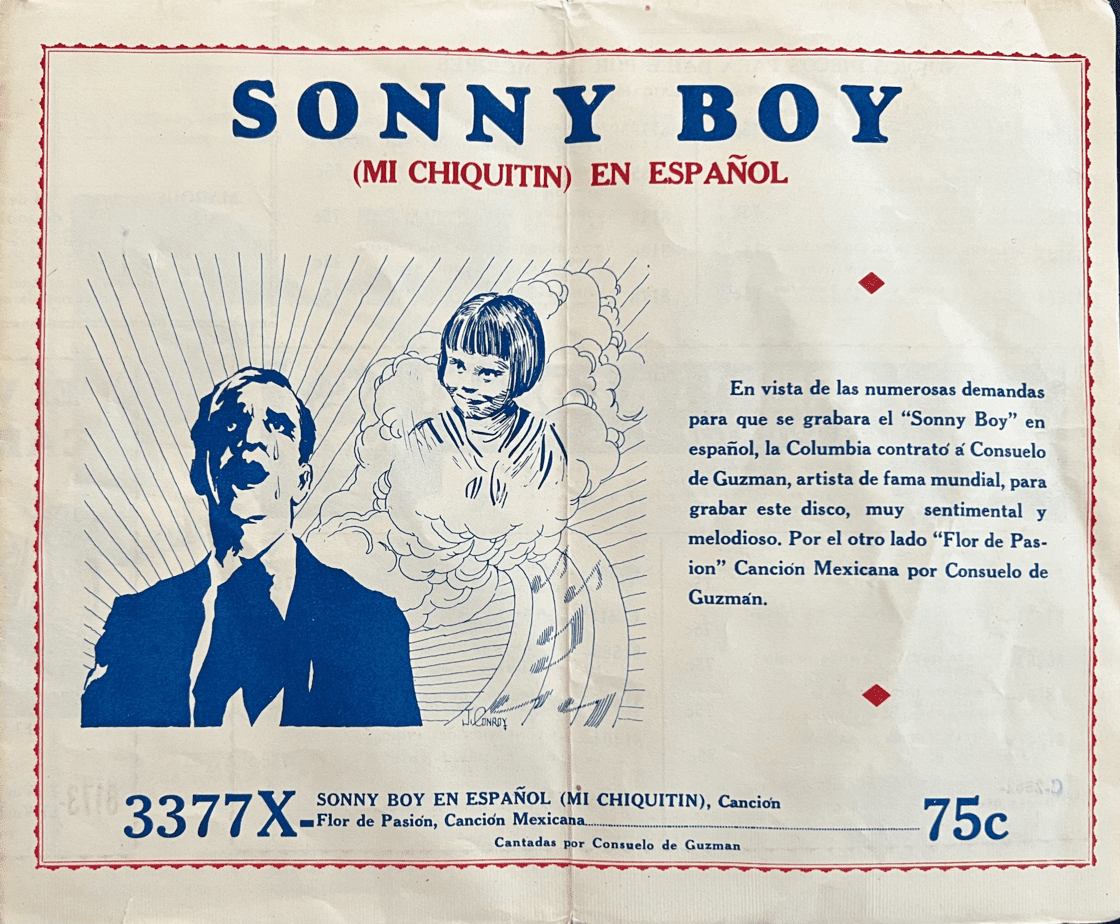

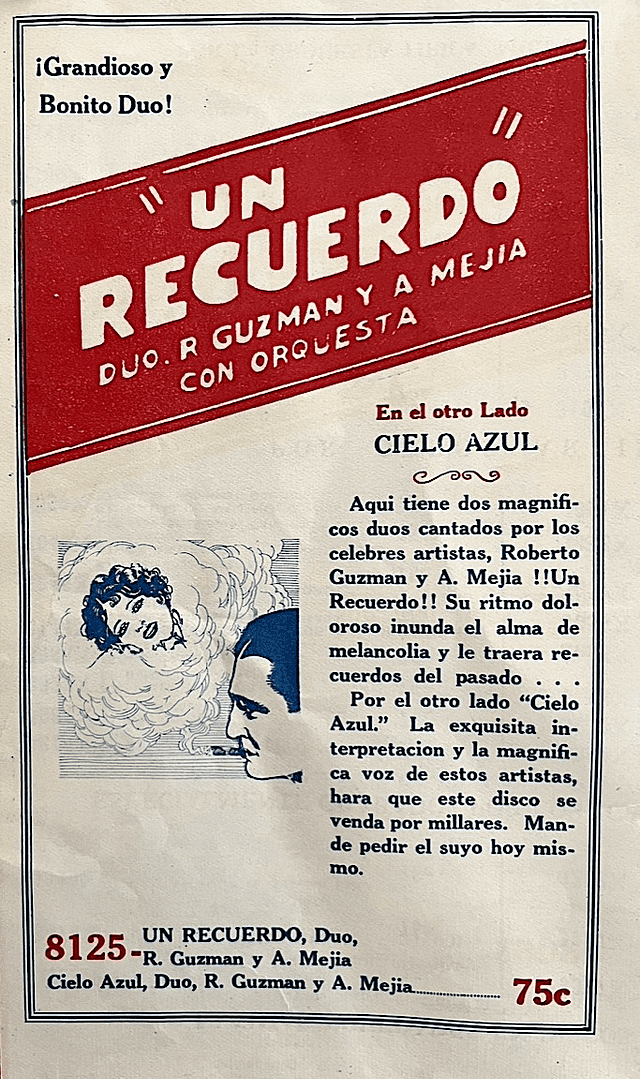

Tastes in Mexican music are obviously changing. The older corridos of the more rural musicians are listed, just not prominently. The music highlighted by the illustrations includes pop songs, rancheras, and dance music. In one case, Al Jolson’s popular song of the day, “Sonny Boy”, has been transformed into a Spanish tearjerker. Mexican music is gradually absorbing American culture. Significantly, there is a large number of female artists.

Also highlighted in the advertisement is Mexican-born, Hollywood actress Delores Del Rio. Del Rio had never recorded—or acted—in her native Mexico. It was her Hollwood career that led Del Rio into a recording studio to sings songs in Spanish. It was her Hollywood career that later would allow her to return to Mexico to act in Mexican movies.

Chris Strachwitz, founder of Arhoolie Records, listened to a dozen or so of the listed 78s: “I can tell that the company’s focus was on the more affluent or high tone middle class Mexicans or Mexican-Americans rather than the more lower working class—reflected in both the artists heard and the song selection! Most of the ads I have collected cater to the more average Mexicanos.”

Regarding the record labels advertised in the St. Louis Music Co. flyer, discographer and music historian Dick Spottswood noted: “Looks like a local [St. Louis] dealer who handled Columbia, Victor, Okeh and Vocalion. Brunswicks are conspicuously missing. It’s from 1928 [based on the record numbers].”

Miscellanous 78 rpm Record Labels

For Mexican Music

When marketing to ethnic groups the American record companies and 78 distributors often resorted to simple, graphic, and sometimes garish pen-and-ink art to advertise their records, and that’s true with this advertisement. But in this case, if it was designed by a Mexican artist then his influence in style may not be coming from the example of the well-known “race record” advertisements in the Chicago Defender, but rather from Mexico, itself, with its own wild tradition of graphic arts for marketing to the lower and middle classes.

There doesn’t seem to have been any data collected as to who in the Mexican and Mexican-American families in the United States did the record buying. The major record companies through market research collected information that showed in White families it was the wife or woman-of-the-house who purchased records for the family. Perhaps this was because traditionally they were the ones who handled the budget and shopped for the family. Although information was more antidotal, the record companies likewise believed the same held true in Black families.

So who bought the 78s in Mexican and Mexican-American households?

Perhaps in earlier days it was men who purchased records devoted to military and police bands, as well as songs of the Mexican Revolution. But times had changed by 1928. The types of music offered in the St Louis Music Co. advertisement, as well as the illustrations used, suggest the company was marketing its records and services to women. Dancing and romance were in the air—and would soon be spinning on the phonograph. No doubt in Mexican and Mexican American families, just like their Black and White counterparts, it was women who did the bulk of the family shopping, and it was these same women who bought most of the records.

Imágenes Seleccionados

Selected Images

Below are selected images from the St. Louis Music Co. mail-order foldout.

Images with Content

Epilogo

Epilogue

[B]y 1940 the majority of Spanish-speakers north of the border were no longer recent immigrants from Mexico, as was the case earlier in the century when the first large wave of Mexican immigrants entered the United States in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Neither were they primarily descendants of the small number of nineteenth-century Mexicans. By World War II, the majority of Spanish-speakers in the Southwest were U.S. born and raised, and unlike an earlier, immigrant generation which still dreamt of returning to Mexico–the Mexican Dream–this new generation identified itself as Mexican-Americans and aspired to the American dream ….

Mario T. Garcia, historian

The advent of the Great Depression in 1929, the year after the St. Louis Music, Co. advertisement was released, would by the early 1930s rewrite the rules for making, marketing, and selling 78 records. Already by the late 1920s radio and motion pictures with sound had begun taking business away from the record companies. In the United States, with a quarter of the population out of work during the Great Depression, the purchase of records became an unaffordable luxury, particularly for working-class Mexicans and Mexican Americans.

During these worst-of-times, 78 record sales plummeted as much as ninety percent. Eventually the record market would rebound as the economy recovered. But it also changed. During the 1930s record companies aided the recovery by slashing record prices and adopting new marketing strategies.

One change in marketing 78s in the Mexican and Mexican American communities was the emphasis on new border and regional sounds, the emergence of Tex-Mex music along the Rio Grande border, and the development of regional Mexican music styles in California.

Many new Mexican families in the United States in the 1920s found musical comfort from the more traditional music of Mexico. But as immigrants established roots in the United States they developed their own music incorporating musical sounds from Mexico with styles heard north of the border. The record companies picked up on this. The Mexican music sold in the United States in the 1920s was from artists residing in Mexico, whereas by the 1930s much of the music sold would be recorded by artists residing in the United States.

Special thanks for the assistance of Russ Shor, Dick Spottswood, Chris Strachwitz, and Dan Vernhettes.

Also, special thanks to Los Místicos de Oro de la Música de Antaño.

For those interested in early Mexican and Mexican-American music, an excellent resource is The Strachwitz Frontera Collection: https://frontera.library.ucla.edu/

Note: the St. Louis Music Co.’s Mexican record advertising foldout is from the collection of Dan Moss. All other ephemera and 78 record labels are from the Bowman collection, except the La Casa de Musica record label sticker that came from the Arhoolie Foundation’s Frontera Collection Archives.