DEATH OF CARRANZA

The 1920s was the heyday for the recording of topical ballads, particularly dramatic stories highlighting the adventures, achievements, or tragic deaths of brave heroes.

No sooner did bold newspaper headlines appear than both amateur and professional songwriters were putting pen to paper and rushing their songs to a record company. The goal, of course, was to get out the first 78 rpm record documenting—or commemorating—an historical event. Topical songs were popular with the public, plus lucrative for the record companies.

In the United States during the 1920s the one event that most gripped the public’s imagination was Charles Lindbergh’s successful solo flight across the Atlantic. On May 20-21, 1927, he made the first non-stop flight from New York to Paris. He earned the nickname “Lucky Lindy”, and soon 78s telling his dramatic story were being shipped to record stores throughout the country. One song was even entitled, Lucky Lindy.

Lindbergh lived to tell his tale and receive a hero’s welcome back home with ticker tape parades. Emilio Carranza wasn’t so lucky.

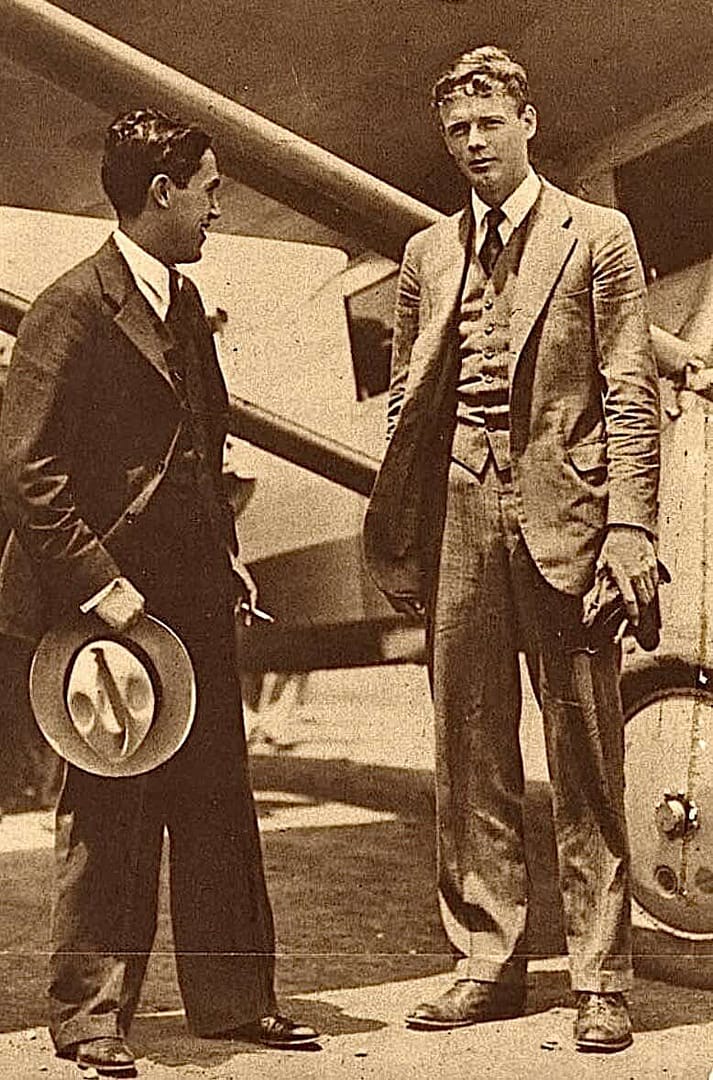

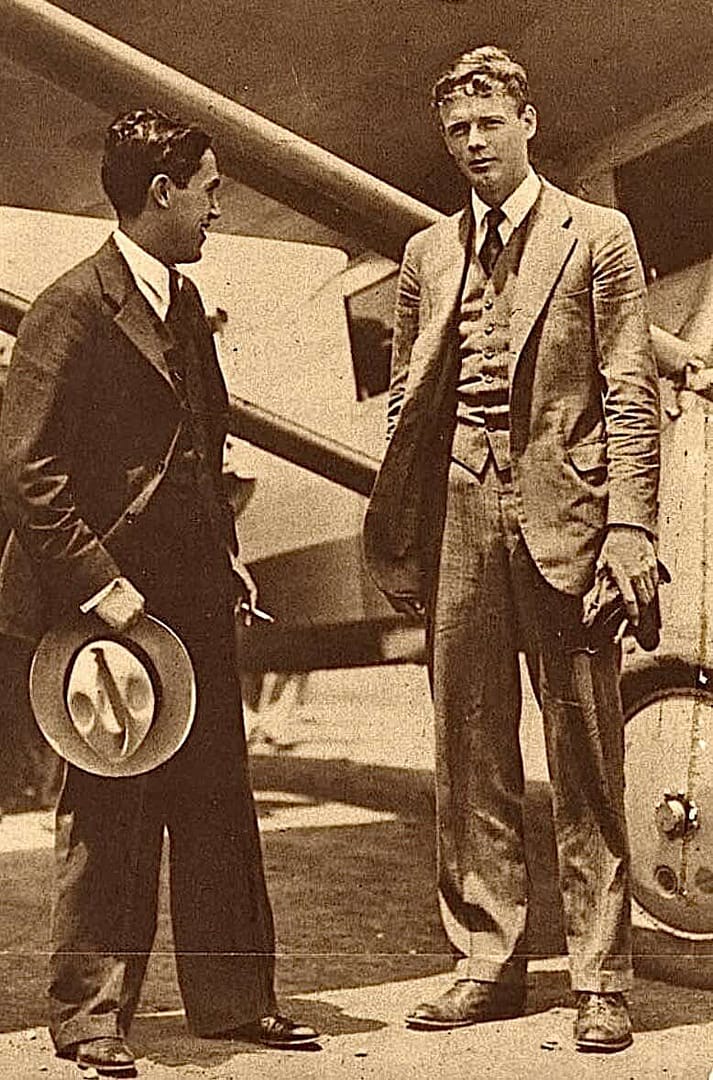

The dapper, uniformed Captain Emilio Carranza is the figure on the right standing in front of his airplane. This photo was taken June 21, 1928, as Carranza was touring the northeast United States following his goodwill flight to Washington D.C. He would die in a plane crash on July 12th, attempting to return to México.

Mexican pioneer aviator Emilio Carranza (1905-1928) had it all: youth; good looks; family connections; endurance and talent; plus the affection of the Mexican public. He was born to be a hero.

Emilio was the great-nephew of Mexican President Venustiano Carranza and the son of a Mexican diplomat serving in the United States, which resulted in his living part of his early life north of the border and becoming fluent in English.

In 1924 he graduated with honors from México’s Heroic Military Academy, shortly afterwards becoming an aviator in the Mexican Army.

Between 1924 and 1928 Carranza became a favorite of the Mexican public for becoming the premier pilot in México in setting long distance flight records in the country. At least one early flight resulted in a serious crash requiring doctors to reconstruct his face.

The 1927 Trans-Atlantic flight by Charles Lindbergh, along with Lindberg’s subsequent flight to México later in the year, prompted Mexican authorities and business interests to propose in 1928 a long-distance “goodwill” flight from Mexico City to Washington D.C. Captain Carranza was designated the pilot of this

The 1927 Trans-Atlantic flight by Charles Lindbergh, along with Lindberg’s subsequent flight to México later in the year, prompted Mexican authorities and business interests to propose in 1928 a long-distance “goodwill” flight from Mexico City to Washington D.C.

Charles Lindbergh and Emilio Carranza became good friends in 1927 after meeting in El Paso.

Captain Carranza was designated the pilot of this historic first which would generate extensive press coverage both in México and the United States. Public fundraising in México, plus a financial contribution by Lindbergh himself, helped fund the undertaking.

Naming his airplane the Mexico “Excelsior”, after the Mexican newspaper promoting the venture, Carranza left Mexico City on June 11, 1928, reaching Washington D.C. the next day where he was feted by American and Mexican officials. He dined at the White House with President Calvin Coolidge. Then he flew on to New York City to once again be honored, this time with a ticker tape parade and Mayor Jimmy Walker handing him the “key to the city”. He shook hands with the funny-man Charlie Chaplin and heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey. Next he gave an honorary review of the cadets at West Point.

Charles Lindbergh and Emilio Carranza became good friends in 1927 after meeting in El Paso.

historic first which would generate extensive press coverage both in México and the United States. Public fundraising in México, plus a financial contribution by Lindbergh himself, helped fund the undertaking.

Naming his airplane the Mexico “Excelsior”, after the Mexican newspaper promoting the venture, Carranza left Mexico City on June 11, 1928, reaching Washington D.C. the next day where he was feted by American and Mexican officials. He dined at the White House with President Calvin Coolidge. Then he flew on to New York City to once again be honored, this time with a ticker tape parade and Mayor Jimmy Walker handing him the “key to the city”. He shook hands with the funny-man Charlie Chaplin and heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey. Next he gave an honorary review of the cadets at West Point.

After being wined and dined throughout the Northeast, Carranza was ready to make his return flight to México. His intent was to fly non-stop from New York City to Mexico City. It would be his last flight. Either the pilot thought he could outrun continuing thunderstorms or could simply plow through them, but neither was the case, his plane crashing July 13th in a pine forest near Mount Holly in southern New Jersey. His body was located the next day.

As so often happens with high profile tragedies, various stories, some probably apocryphal, began quickly circulating to fill in the blanks of as to what happened. After all, why would an experienced pilot tempt fate by flying into a storm? It was a mystery.

Even his friend Lindbergh, according to one story, had urged Carranza to postpone takeoff. Others related that he was under direct orders of his superiors—perhaps worried that Carranza was enjoying the hero’s life too much in the United States—to return to Mexico immediately. Then there was a newspaper article in which a United States senator reported that there had been a plot to kill Carranza.

Carranza’s body was returned to Mexico City with full honors and an outpouring of grief. He was given a national hero’s funeral with an estimated 100,000 mourners marching in the procession. México awarded him the honorary rank of general. Watching the proceedings was his pregnant wife, a bride for only four months.

In Mexico City, Carranza was buried in the National Rotunda of Illustrious Persons. In New Jersey, a memorial, funded by pennies from Mexican students, was erected at the site of the crash to commemorate his death. It still stands.

Several months after Carranza’s death the Trio Ramos from México entered the Vocalion recording studio in Chicago. On October 26, 1928 the musicians recorded with orchestra backing their two-part corrido, telling the final story of the young Mexican aviation hero Emilio Carranza and his flight of death: El Vuelo de Carranza—“El Vuelo de la Muerte”.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

For an insightful documentary on the life and death of Emilio Carranza check out “Flying With Emilio”. See link below:

For more information on the recording of El Vuela de Carranza check out the below link to the Strachwitz Frontera Collection:

https://frontera.library.ucla.edu/recordings/el-vuelo-de-carranza-primera-parte-0

A recent book, albeit brief, detailing the life of Emilio Carranza is:

Leticia Roa Nixon & Rosa Mercedes Pujols. The Mexican Lindberg: Captain Emilio Carranza. Author House. 2011.

All photos are taken from the internet.