The Midnight Special

&

Pistol Pete

When Otto Gray took McGinty’s Oklahoma Cowboy Band to St. Louis in 1926, in order to record for Okeh Records, the band members waxed two sides: Cowboy’s Dream, and Pistol Pete’s Midnight Special. This was the band’s first foray into the recording studio.

Cowboy’s Dream is truly an ensemble effort by the band and a very lovely piece, one giving the listener a feel for what a well-rehearsed string band composed of cowboy musicians could sound like.

The other side of the released 78 record, Pistol Pete’s Midnight Special, was by band member Dave Cutrell, AKA “Pistol Pete”, with—according to the label—“Accomp. by McGinty’s Oklahoma Cow Boy Band”. The only problem is that the band never played on this song. Although the band got credit, it was just Cutrell singing and gently strumming his guitar.

The band, in fact, lost out in making musical history.

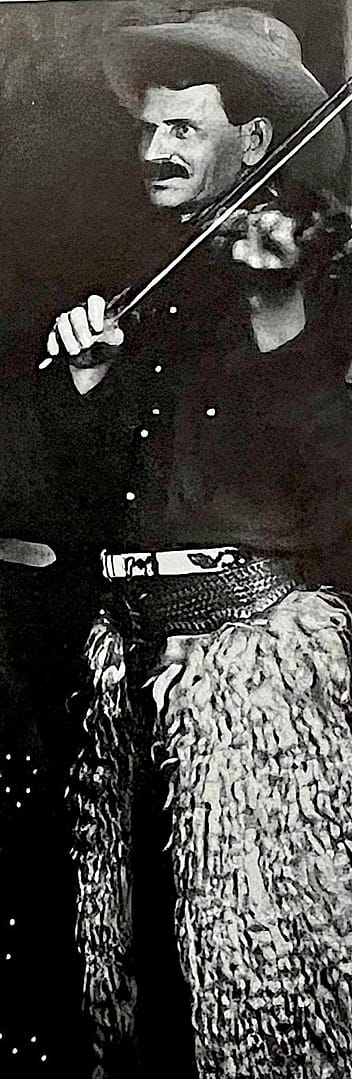

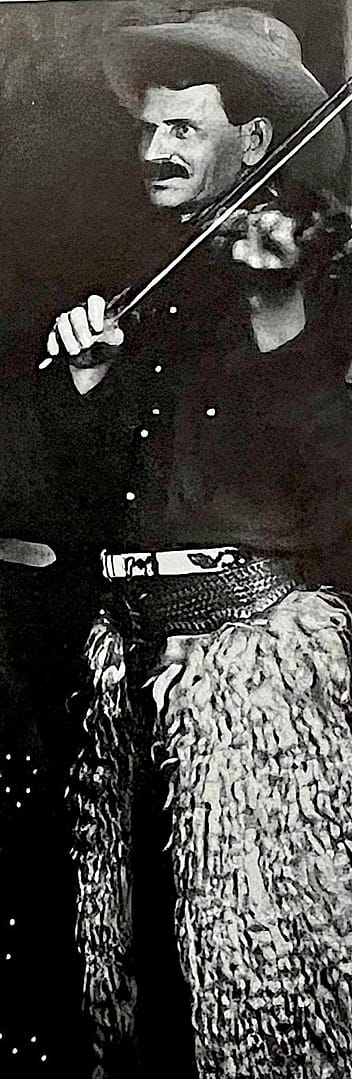

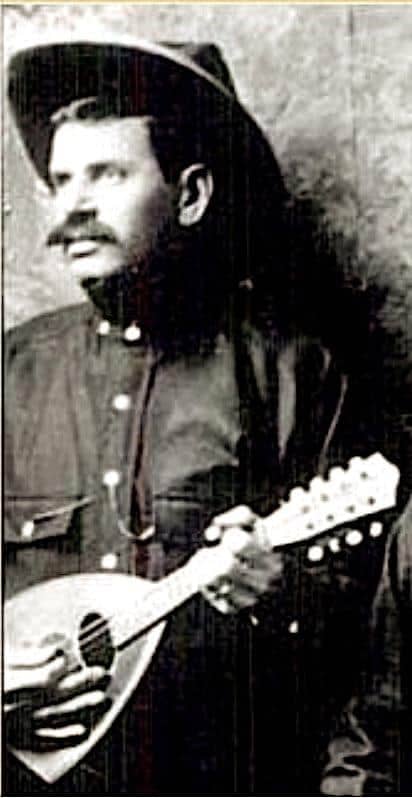

OLD TIME MUSICIAN DAVE “PISTOL PETE” CUTRELL WHILE HE WAS PLAYING WITH McGINTY’S OKLAHOMA COWBOY BAND IN 1926.

When Otto Gray took McGinty’s Oklahoma Cowboy Band to St. Louis in 1926, in order to record for Okeh Records, the band members waxed two sides: Cowboy’s Dream, and Pistol Pete’s Midnight Special. This was the band’s first foray into the recording studio.

Cowboy’s Dream is truly an ensemble effort by the band and a very lovely piece, one giving the listener a feel for what a well-rehearsed string band composed of cowboy musicians could sound like.

The other side of the released 78 record, Pistol Pete’s Midnight Special, was by band member Dave Cutrell, AKA “Pistol Pete”, with—according to the label—“Accomp. by McGinty’s Oklahoma Cow Boy Band”. The only problem is that the band never played on this song. Although the band got credit, it was just Cutrell singing and gently strumming his guitar.

OLD TIME MUSICIAN DAVE “PISTOL PETE” CUTRELL WHILE HE WAS PLAYING WITH McGINTY’S OKLAHOMA COWBOY BAND IN 1926.

The band, in fact, lost out in making musical history.

What makes Pistol Pete’s Midnight Special of particular interest to music historians is that it is the earliest commercial American version of the song that the Black folksinger Lead Belly would popularize in the 1930s as Midnight Special.

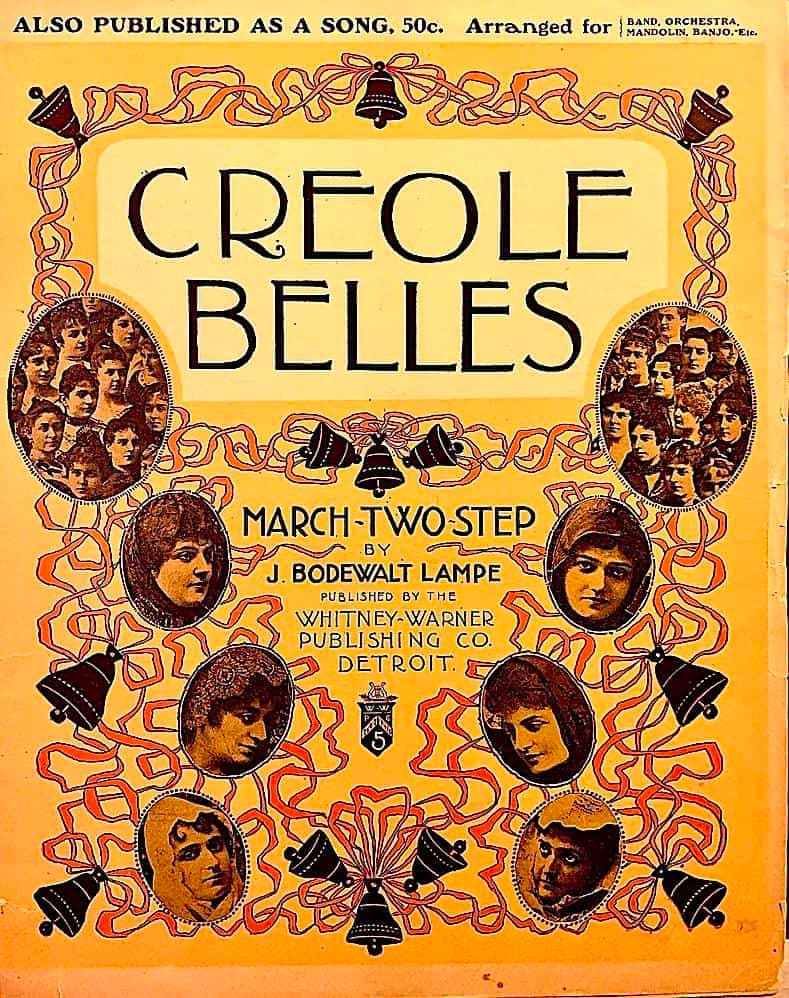

Theories, conjectures, and tall tales abound about what is the meaning of “Midnight Special”. They could fill a book—or at least an extended chapter in a book on folksongs. There’s general agreement that the basis of the song’s melody is derived from a popular tune of the Ragtime Era, Creole Belles, written by J. Bodewell Lampe and George Sidney in 1901.

As early as 1905, snippets of lyrics by Black singers, words that would later become part of “Midnight Special”, were noted by folksong collectors:

Get up in the mornin’ when the ding dong rings

Look at the table—see the same damn thing

Sometime soon after, the Black folk lyrics and the Ragtime Era tune would merge into the famous song we know today:

Let the Midnight Special shine its light on me …

Let the Midnight Special shine her ever-loving light on me

The song details the longings of prisoners confined behind prison walls, with the “Midnight Special” clearly being a train representing dreams of freedom. Although it was crafted by Blacks from numerous “floating verses” in their song world, it would become popular with both Black and White singers, with one of those White singers being Dave Cutrell.

When he joined McGinty’s Oklahoma Cowboy Band, Dave Cutrell was a jack-of-all-trades, a singer and multi-instrumentalist (guitar, mandolin, and fiddle), and someone who fit into the category of “semi-professional musician”. “Pistol Pete” could have been his stage name or simply a nickname based on the luxuriant mustache he sported reminding many locals of a famous Oklahoma lawman—Frank “Pistol Pete” Eaton—who likewise wore a similar trademark mustache.

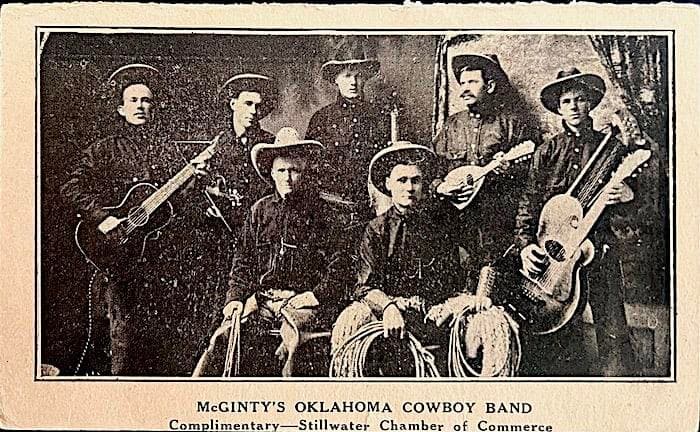

Dave Cutrell, holding his mandolin, is shown in this 1926 photo of Billy McGinty’s Oklahoma Cowboy Band. Cutrell is standing second from the right.

Davis A. Cutrell was born into a large family in Louisville, Kentucky, on September 16, 1878, the son of a miner/farmer. When young, he moved with his family to the Midwest, and by the time he died in 1961, he had lived in Illinois, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma. He left school after the eighth grade. Cutrell married young (and often) and had at least two daughters and one son. One suspects there may have been others, unaccounted children. At some point before 1918 he lost his right eye. During various times in his life Cutrell worked as a laborer, farmer, cook, hotel employee, carpenter, and, of course, musician.

Ironically, despite his playing in a cowboy band, there is no mention of Cutrell ever working as a cowboy; we do know, however, that for a period of time he tried to earn a living as a musician. In the 1930 Federal census his occupation is shown as “musician”, and it was noted that he was employed in an “orchestra”, although because he was residing then in the small town of Cushing, Oklahoma, maybe the census taker meant to write down “band”. He was remembered during the last twenty-five years of his life for his fiddle playing at dances in the Joplin, Missouri area.

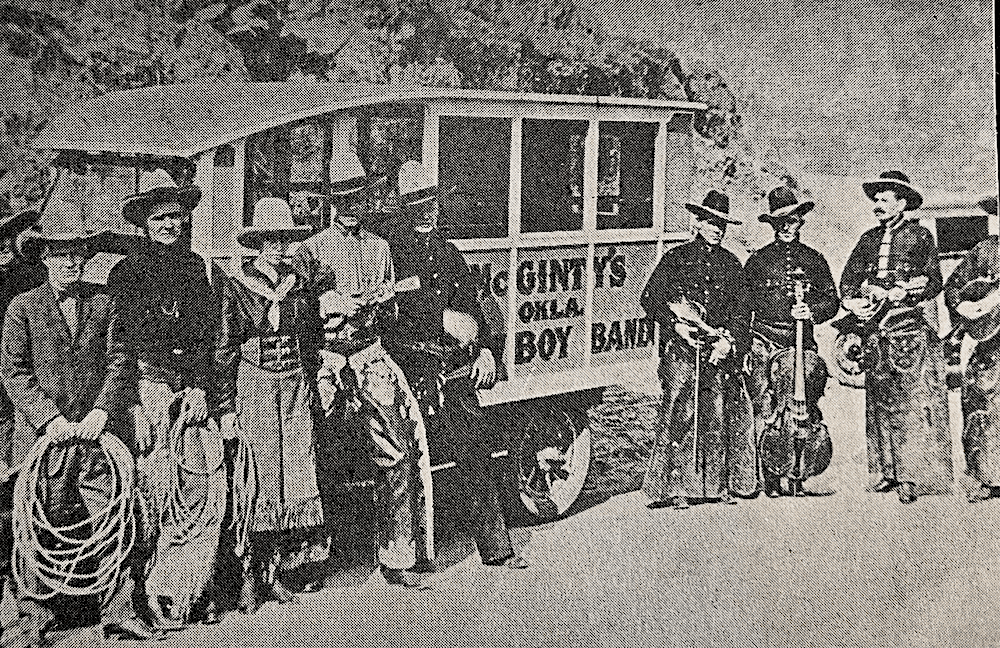

This postcard may show those members of McGinty’s Oklahoma Cowboy Band who traveled to St. Louis in early 1926 to record for Okeh Records. His trademark mustache identifies Dave “Pistol Pete” Cutrell, standing second from right.

Cutrell was not a member of the initial incarnation of the Oklahoma Cowboys; at least the earliest photos of the band don’t show his presence—and with the full, dark mustache he would be hard to miss. Perhaps he was added to the band soon after fame came its way because he was holding himself out as a professional musician, and the band needed a shot of professionalism.

Ultimately Cutrell’s tenure with the Oklahoma Cowboys was brief. He was playing with the band in 1926 when it was under Billy McGinty’s name, but seems to have left once Otto Gray turned it into a permanent touring outfit.

Cutrell’s recorded version of Pistol Pete’s Midnight Special is a fairly close approximation of the song that Lead Belly sang and popularized, such that one’s first thought is that Cutrell got his rendition from a Lead Belly recording. But timewise that can’t be. Lead Belly’s initial recording of Midnight Special for folksong collectors John and Alan Lomax was in 1934, eight years after Cutrell waxed his version.

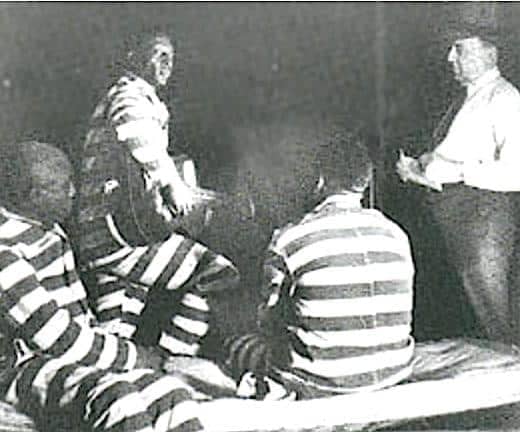

Staged photo of Lead Belly in prison playing guitar for folksong collector John Lomax.

Between 1915 and 1934, Lead Belly served prison sentences in both Texas and Louisiana, and he probably picked up the song from fellow Black inmates, while working on the Sugerland prison farm near Houston.

Lead Belly had been serving time at Sugerland on a murder charge, and the oft-told story is that he sang his way out of prison by performing for Governor Pat Neff when he toured the facility in 1924. One of the songs Lead Belly sang for the governor in his musical plea for freedom was Midnight Special. By early 1925—the same year McGinty’s Oklahoma Cowboy Band was formed—Lead Belly walked out of prison with a pardon in his hand.

Of all the songs he learned at Sugarland, however, by far the most popular was “Midnight Special.” Leadbelly did not write all the song, although he probably did add some elements to it…. Parts of the song were clearly circulating in folk tradition prior to [his} encountering them and he may have known of it prior to his days in Sugarland.

Charles Wolfe & Kip Lornell

Because of the song’s structure and lyrical cadence it could very well have served as a prison farm “work song”, sung and chanted as Black prisoners toiled in the Texas fields. Long before Lead Belly’s final release from prison, “Midnight Special”, the song that he would make famous, had already escaped the walls and chains, making itself popular in the outside world, and that is where Dave Cutrell stumbled upon it.

According to Norm Cohen in his classic study of train songs:

Before long the [Oklahoma Cowboys] were joined by Dave Cutrell, an old-time musician from Drumright, Oklahoma, nicknamed “Pistol Pete.” Cutrell was best known for his rendition of “Midnight Special,” and it was requested of him any time he appeared in concert. In late 1925 or early 1926, Otto Gray of Stillwater took over leadership of the band. Both Gray and McGinty are mentioned in Cutrell’s rendition, recorded in May, 1926.

We don’t know how Cutrell learned Midnight Special, but by the mid-1920s it had spread through much of the country, particularly areas with large Black populations; it had also begun to become popular with White musicians and singers. Perhaps what warranted Cutrell’s recorded version being named after him, Pistol Pete’s Midnight Special, was his making it his own by personalizing the song’s lyrics as he did on the Okeh recording:

Now, Mr. McGinty is a good man,

But he’s run away now with a cowboy band.

Now Otto Gray, is a Stillwater man.

But he’s the manager now of a cowboy band.

Dave Cutrell’s Okeh recording didn’t set the hillbilly music world on fire, and his 78 only sold modestly. But the song must have proved popular with fans of Otto Gray and his Oklahoma Cowboys because the band recorded its own version for Vocalion in 1929, this time with Otto’s son Owen taking the lead vocals. By then, Pistol Pete was long gone.

After Cutrell recorded his version of “Midnight Special” the recording studio doors opened: bluesman Sam Collins recorded the song as The Midnight Special Blues in 1927; “Watts and Wilson”, a White duo out of North Carolina, recorded it as Walk Right in Belmont in 1927; another White artist, Roy Martin, recorded it as North Carolina Blues in 1930; Blues pianist Romeo Nelson recorded it as 11:29 Blues in 1930; hillbilly artist Bill Cox recorded it as Midnight Special in 1933; Black Texas prisoner Ernest “Mexico” Williams recorded it as Midnight Special in 1933 for John Lomax; and Lead Belly recorded his earliest version of Midnight Special in 1934 for Lomax while still serving time in Louisiana’s Angola prison.

Tracking the evolution of folk songs never proceeds along straight lines, with some mysteries invariably left unsolved.

For instance, the most intriguing version of “Midnight Special” was not even recorded in America, but in England in 1926, shortly before Dave Cutrell waxed his rendition. On the Midnight Special, recorded by Greening’s Dance Orchestra—a prolific recording band—for the British Imperial label, is in actuality the earliest recording of “Midnight Special”.

On the Midnight Special is a jaunty, British-sounding dance tune with a Ragtime feel that mixes other music with a recurring and recognizable “Midnight Special” refrain. Just when you begin to wonder if the song is truly a version of our “Midnight Special”, the vocalist jumps in near the end of the music singing: “On the Midnight Special, shine your lights on me ….”

Link to On the Midnight Special:

How this quintessentially American song jumped the waters to England in 1926 is a brain twister. This recording is a far cry from the laconic version Pistol Pete recorded in St.Louis shortly afterwards.

As for Dave Cutrell, Pistol Pete’s Midnight Special was his one and only recording, as well as his only claim to musical fame. The humdrum of daily life had opened briefly for him at age 47, and then it quickly closed. He had waxed an historic record, but it would take music historians looking back in time to recognize it as such. Cutrell simply moved on.

One suspects that besides pursuing a career in music, Cutrell’s other permanent pastime was pursuing women. Perhaps having a nickname like “Pistol Pete”, along with the eye-catching mustache, increased his appeal to the opposite sex. He was handsome, and it seems he lived life as a likable rogue.

Cutrell was 21 years old when in 1898 he married for the first time. His wife, Maud (or Maude) Murphy, was only 16 years old and still in high school. The marriage is a series of puzzles.

Although there was a marriage certificate for the couple, at first glance it seems like the marriage was annulled. The bride kept her maiden name, lived with her parents in Iowa after the marriage for much of her adult life—later living with her younger sister’s family, and never identified herself as being married to Cutrell, except once. Yet, five years after the marriage, in 1903, the couple had a daughter who took her father’s name. The daughter would later make Omaha her home, as would Maud. In 1907 the couple had a second daughter, who also took her father’s name. Then in 1913 they had a son. There is no documentation showing any of the children ever lived with Maud—or Dave. Neither is there documentation of Dave and Maud living together.

Mysteriously in 1916 a Maude Cutrell surfaced in Omaha, identifying herself in a street directory as the widow of Davis Cutrell. Did Maude really think her husband was dead? In 1910 she had been a teacher in Iowa. Now in Omaha she was working as a packer for Morris and Co. Later she would marry a man named John Hurt and reside in Omaha for the remainder of her life.

We don’t know how Dave Cutrell was employed between 1898 and 1918, from ages 21 to 40, other than occasionally working as a laborer. But we know he didn’t die. Surely during this time period there were other relationships, if not marriages. And there must have been plenty of music.

In 1918, Cutrell was managing a hotel in Pemeta, Oklahoma, and living with a Cadie (or Eadie?) Cutrell, who may have been a short-term wife.

It seems likely that Cutrell began his semi-professional music career at least by the early 1920s when he was living in Drumright, Oklahoma. He was working in town in 1920, employed as a restaurant cook. He claimed to be married, but was not living with his wife.

Dave “Pistol Pete” Cutrell joined McGinty’s Oklahoma Cowboys in 1926, and recorded his one record.

In 1930, Cutrell was living in Cushing, Oklahoma, and had remarried. His new wife was twenty one years younger, and was the manager of a local cafe. At that point in his life Cutrell considered his occupation to be as a musician, although he might have helped his wife with cooking at the cafe.

By 1935 Cutrell was living in Galena, Kansas, holding himself out as a carpenter, but with the Great Depression he was barely getting any work.

He was still in Galena in 1940, residing with a “housekeeper” who in reality was probably one of the many women that Cutrell lived with during his life. She was his age, and obviously Cutrell didn’t have the money to employ a housekeeper. In 1942, he was trying to get work through WPA projects in Galena. A year later he was living by himself.

In 1950, he still called Galena his home and now had another wife. He was 72 years old and unable to work. Two years later he was living alone.

Pistol Pete died in a Joplin, Missouri, hospital in1961, following a heart attack at his home in Galena. By then, he was married once again. At the time of his death Cutrell had at least fifteen grandchildren and ten great-grand children. His two daughters by Maud were still alive. He was buried in his hometown.

In death, Dave Cutrell—popular musician, recorder of “Midnight Special”, and “ladies man”—merged with his alter ego, “Pistol Pete”. His cemetery marker simply identified him as “Pete Cutrell”. The only thing missing on the marker was an engraving of his mustache.

Note: All postcards and other ephemera from the Bowman collection, except Imperial record label and tombstone images are from the internet.