Curtis Mosby

The Mayor of Central Avenue

Central Avenue in Los Angeles was the center of Black jazz and entertainment in California in the first half of the twentieth century, and bandleader Curtis Mosby had the honorary title of “Mayor of Central Avenue”, his presence there being so pervasive in the 1920s and 1930s.

Although Mosby is not well remembered today, a number of well-known musicians and singers were in his bands on the West Coast, including Lionel Hampton, Les Hite, Buck Clayton, Lawrence Brown, Ivie Anderson, and Johnny Otis.

In his day, Mosby seemed to be everywhere, wearing many hats.

Above is his business card from the mid-1920s advertising his band: “Curtis Mosby and His Dixie Land Blue Blowers”. Mosby probably handed out thousands of these cards as he was promoting his latest musical venture. This one came out of a scrapbook.

Below is the front of the same business card showing Mosby and his band, with him standing in the middle.

Mosby was a musical entrepreneur. In addition to running his bands, he was a night club owner, a record store owner, a recording artist, a musical promoter, and a performer with his band in five early Hollywood movies. He knew how to publicize his music, as well as how to keep his bands steadily employed. He wasn’t a shy man, and made his presence known in Black entertainment in both Los Angeles and the Oakland/San Francisco area.

The one thing we are unsure of regarding his musical activities were his abilities as a musician. He represented himself to be a drummer—and on occasion, a violinist. On the above band photo on his business card, Mosby is holding a pair of drumsticks. Brian Rust, in his jazz discography, credits Mosby with playing drums on the 1927, 1928, and 1929, records that “Curtis Mosby and His Dixieland Blue Blowers” recorded for Columbia Records in Los Angeles.

Yet …

“Mosby couldn’t drum to save his life,” said one of his band members, explaining that on important engagements and recording sessions Mosby would hire Lionel Hampton. A number of Mosby’s musicians had mixed feelings about him and his musical talents; given his reputation for not paying them, their memories of his drumming abilities might have been biased.

Mosby also had a reputation of underpaying his taxes. This caught up with him in the form of his nightclubs being shut down, and his eventually going to prison in the 1940s for hiding assets in a bankruptcy. Explained one employee about Mosby, “He was a little crooked.”

Mosby, born in either Kansas City, Kansas or Missouri, in 1895, started his first band in Chicago prior to 1920. He opened a music shop in Oakland in 1921, and then toured the country with Mamie Smith and her Jazz Hounds, before returning to California, now taking up residence in Los Angeles.

Setting up his business operations on Central Avenue, in 1924, he formed his “Dixieland Blue Blowers” band—usually a sextette—that for the next couple of years would play for large “Whites Only” crowds at Soloman’s Dance Pavilion Deluxe. In 1926 and 1927, the Dixieland Blue Blowers moved, becoming the house band for the Lincoln Theater, the first all-Black theater on the West Coast.

In 1927, Mosby’s band began its first of three recording sessions for Columbia Records. This would enhance the band’s stature. Its first release, “Weary Blues”, coupled with “In My Dreams (I’m Jealous of You)” was popular, and sold well.

Then in 1928, Curtis opened what would become one of the most famous Black night clubs on Central Avenue, the Apex Club. It was an elegant entertainment hotspot for well-to-do Blacks in Los Angeles, as well as White actors and entertainers “slumming” from Hollywood. Remote radio broadcasts from the club, introduced the Dixieland Blue Blowers to the surrounding areas. Mosby would soon open a second Apex Club in San Francisco.

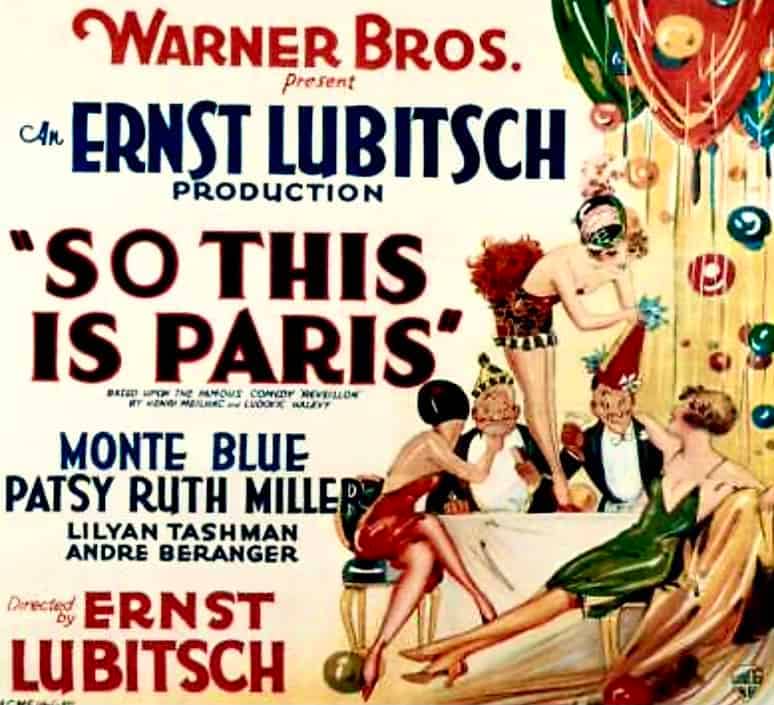

For Mosby, being on the West Coast near Hollywood made it tempting to get himself and his bands into the movies. From 1926 through 1930 they appeared in five films: “So This is Paris” (1926); “Thunderbolt” (1929); “Hallelujah” (1929); a film short, “Music Hath Harms” (1929); and a second film short, “Minstrel Days” (1930).

The advent of the Great Depression in 1929, portended a decline in Curtis Mosby’s fortunes. He sold the Apex Club, but evidently kept a financial interest. Its new owners renamed it the “Club Alabam”. When the club later shut down in the 1930s, Mosby would reopen it. Mosby served time in a California prison in the mid-1940s for his financial transgressions. Once out, he resumed his night club operations.

Almost to the end, Mosby would continue his wheelings and dealings in the music business on the West Coast. The “Mayor” of Los Angeles’ Central Avenue died in San Francisco in 1957.

The advent of the Great Depression in 1929, portended a decline in Curtis Mosby’s fortunes. He sold the Apex Club, but evidently kept a financial interest. Its new owners renamed it the “Club Alabam”. When the club later shut down in the 1930s, Mosby would reopen it. Mosby served time in a California prison in the mid-1940s for his financial transgressions. Once out, he resumed his night club operations.

Almost to the end, Mosby would continue his wheelings and dealings in the music business on the West Coast. The “Mayor” of Los Angeles’ Central Avenue died in San Francisco in 1957.

All ephemera on this page comes from the Bowman Collection.